Black Photo Album

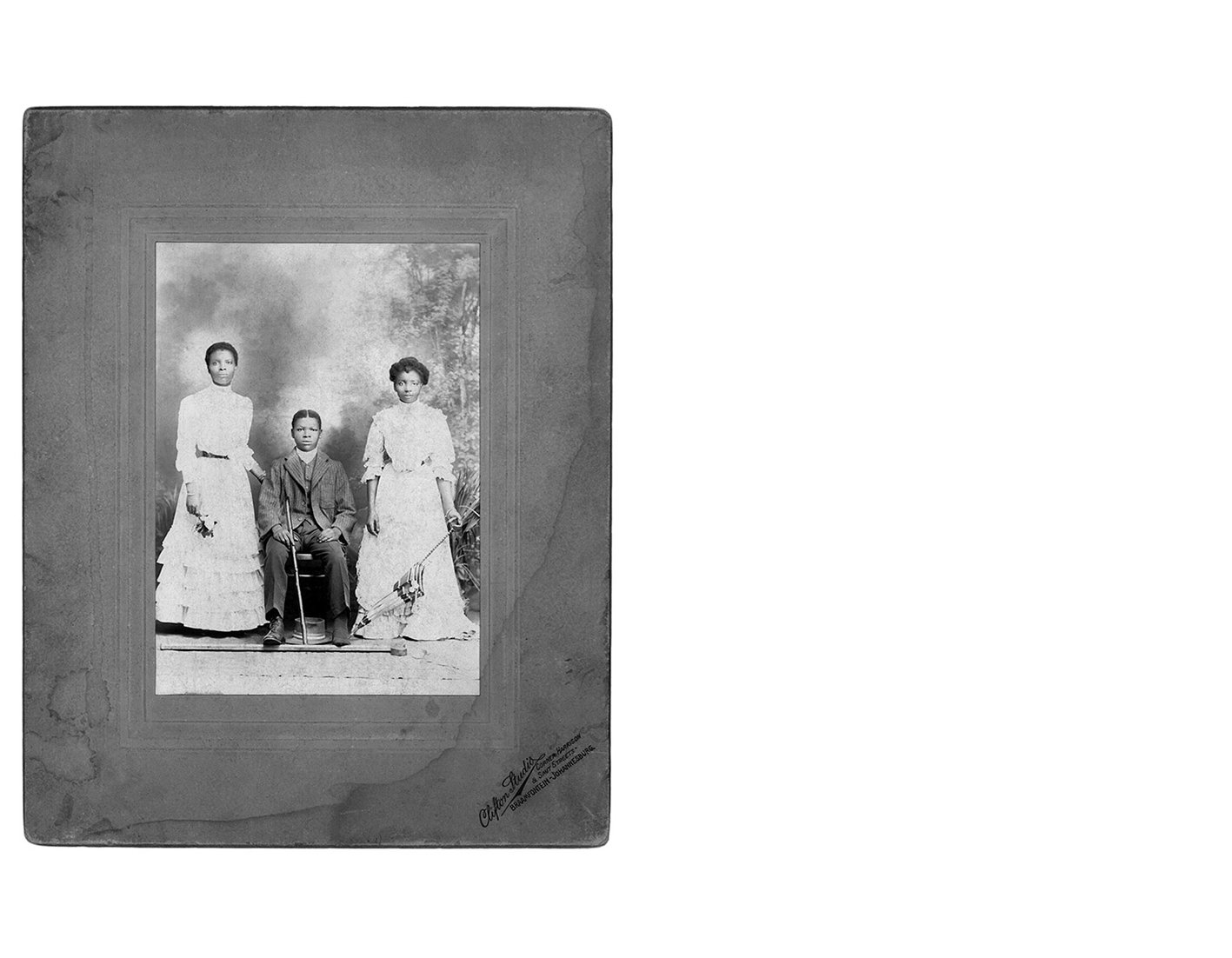

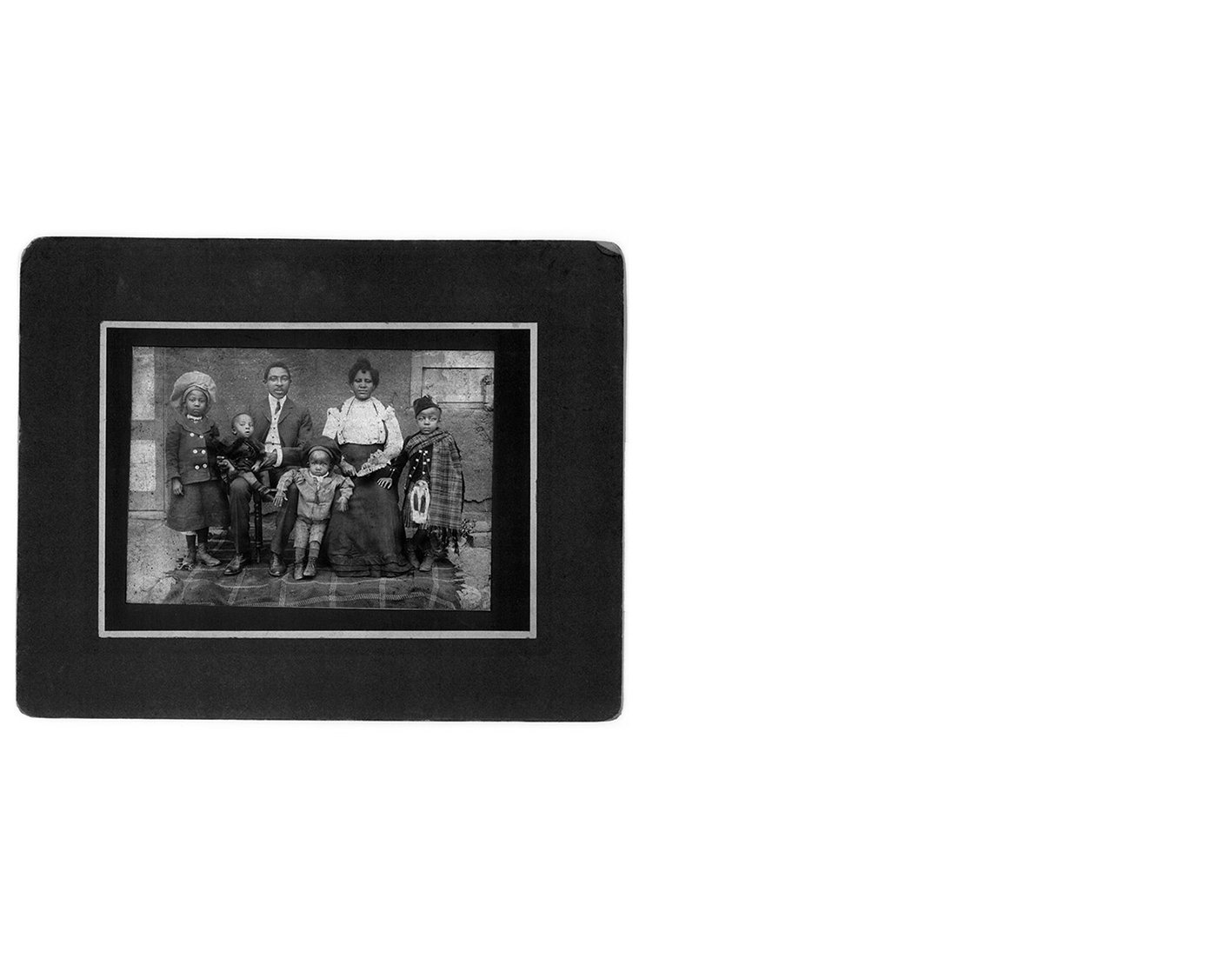

The Black Photo Album/ Look at me: 1890 - 1950 80 black and white slide projection/ 1997

“… with the so-called civilized workers, almost without exception their civilization was only skin deep.”

O. Pirow, quoting South African Prime Minister J. B. M. Hertzog

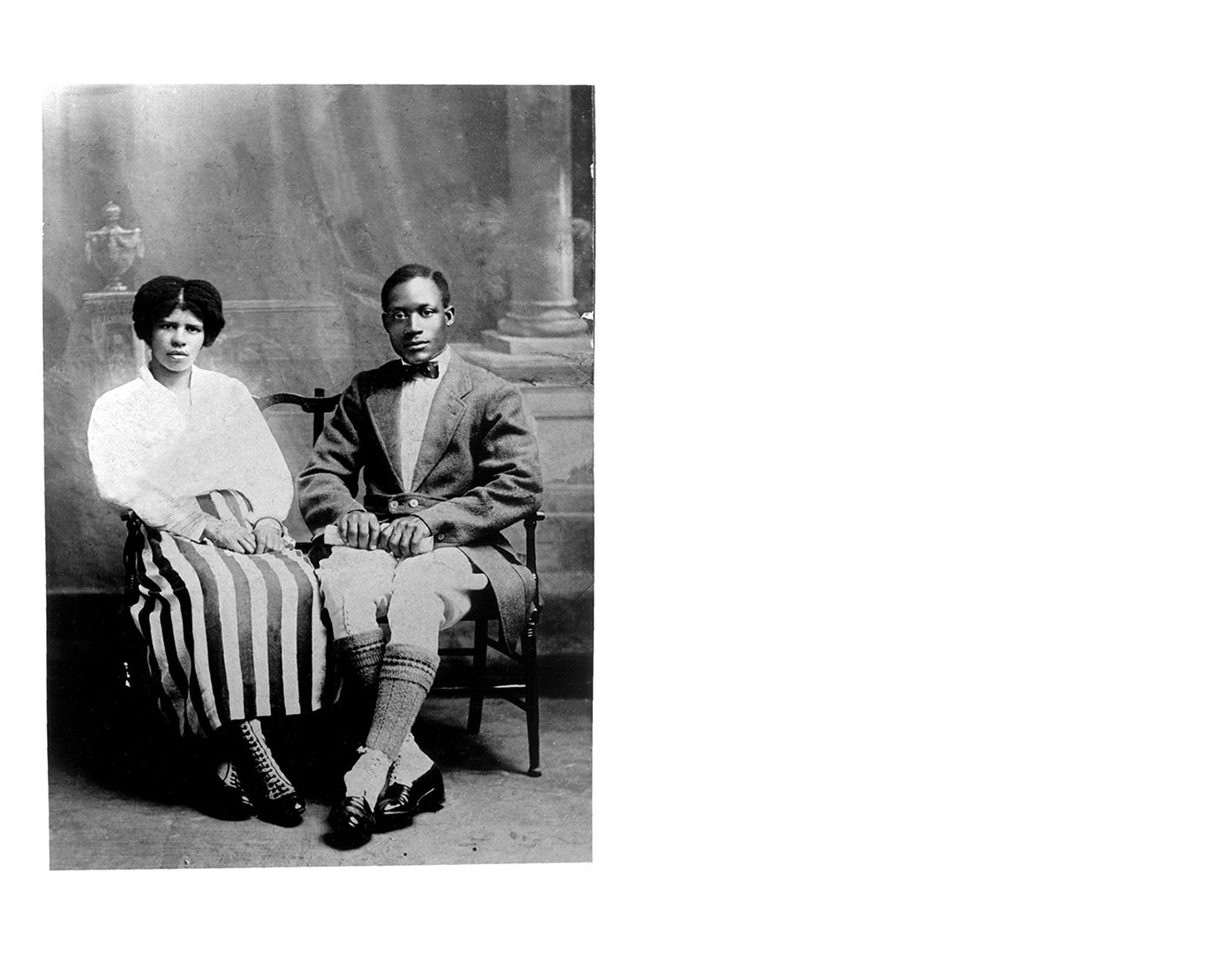

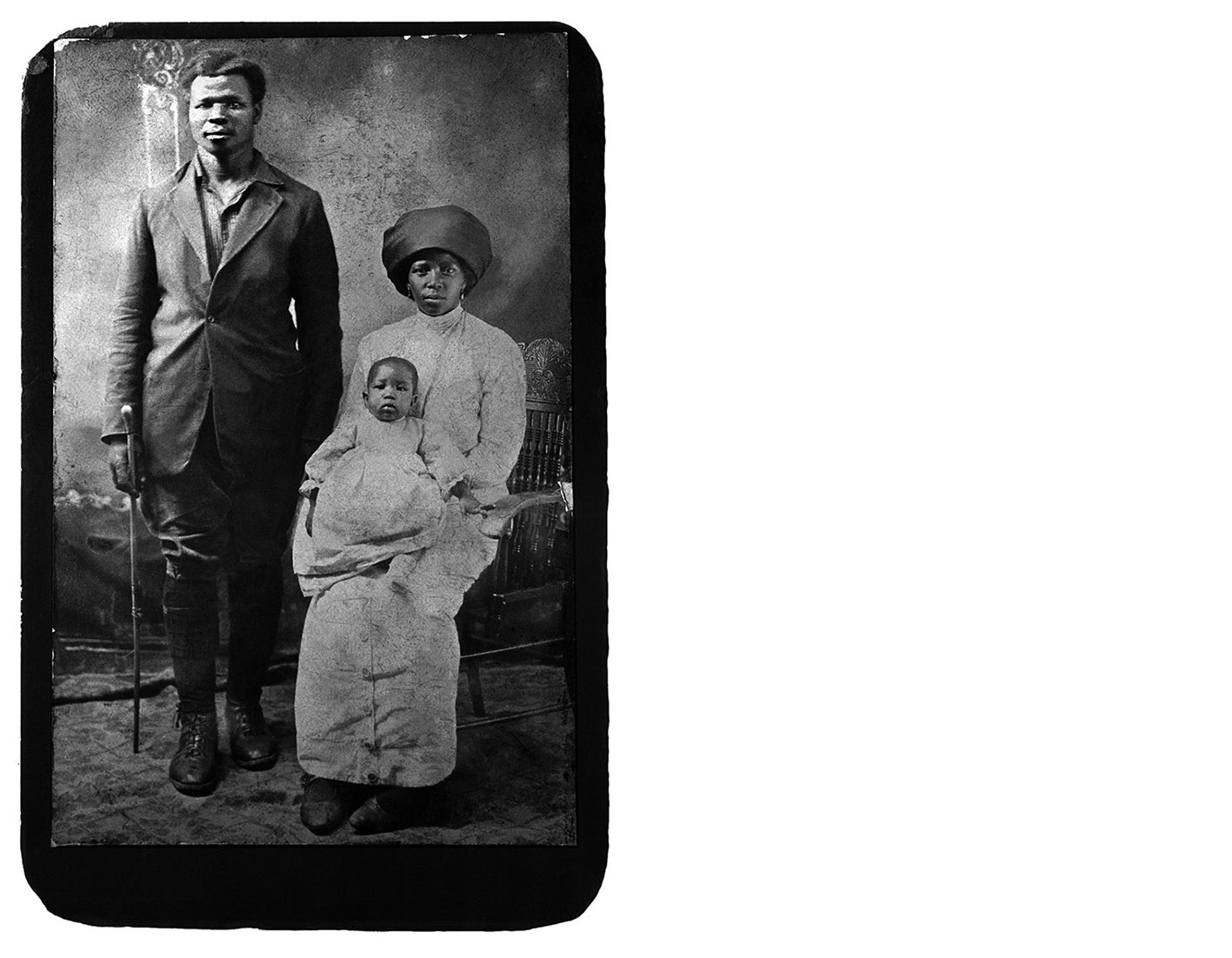

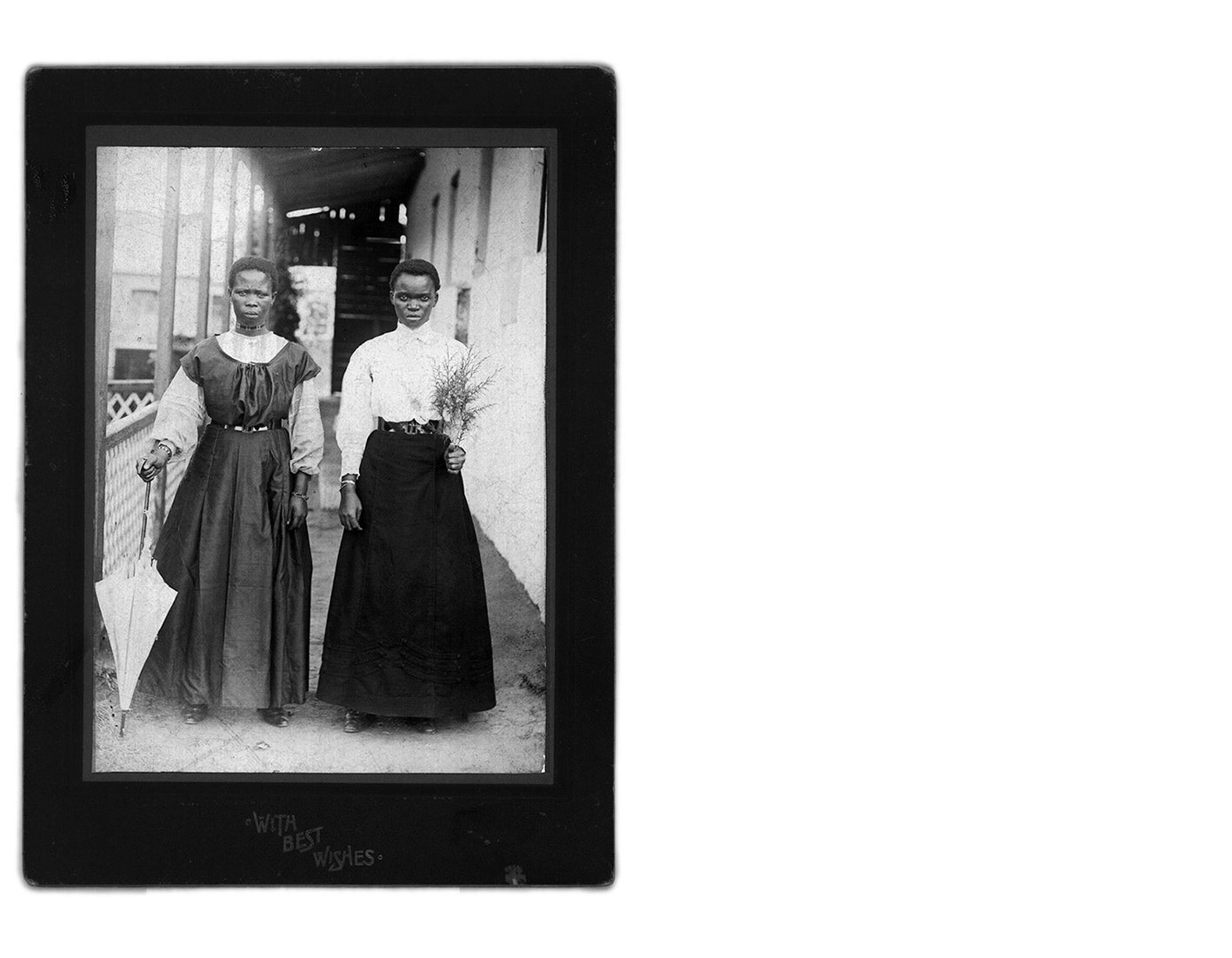

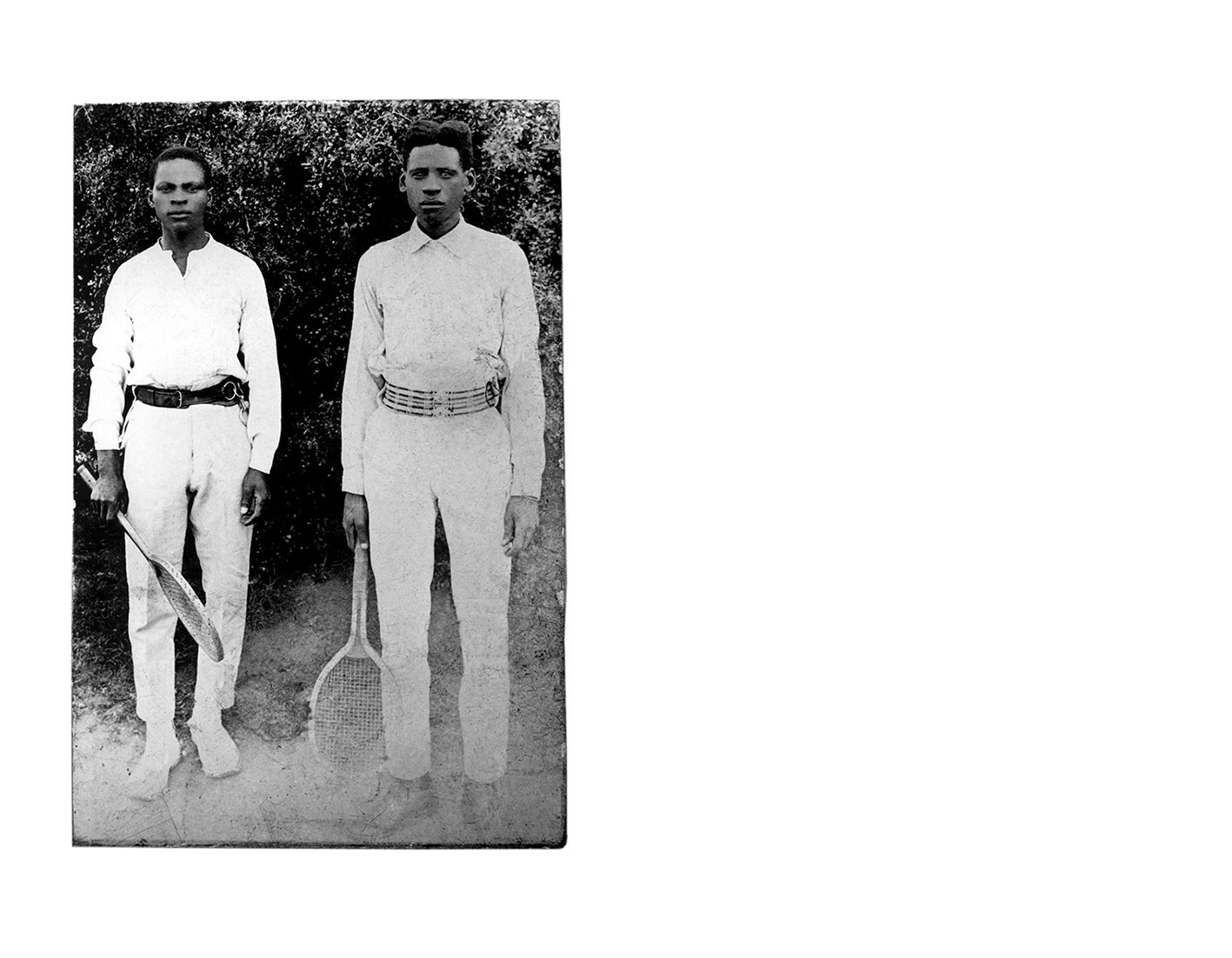

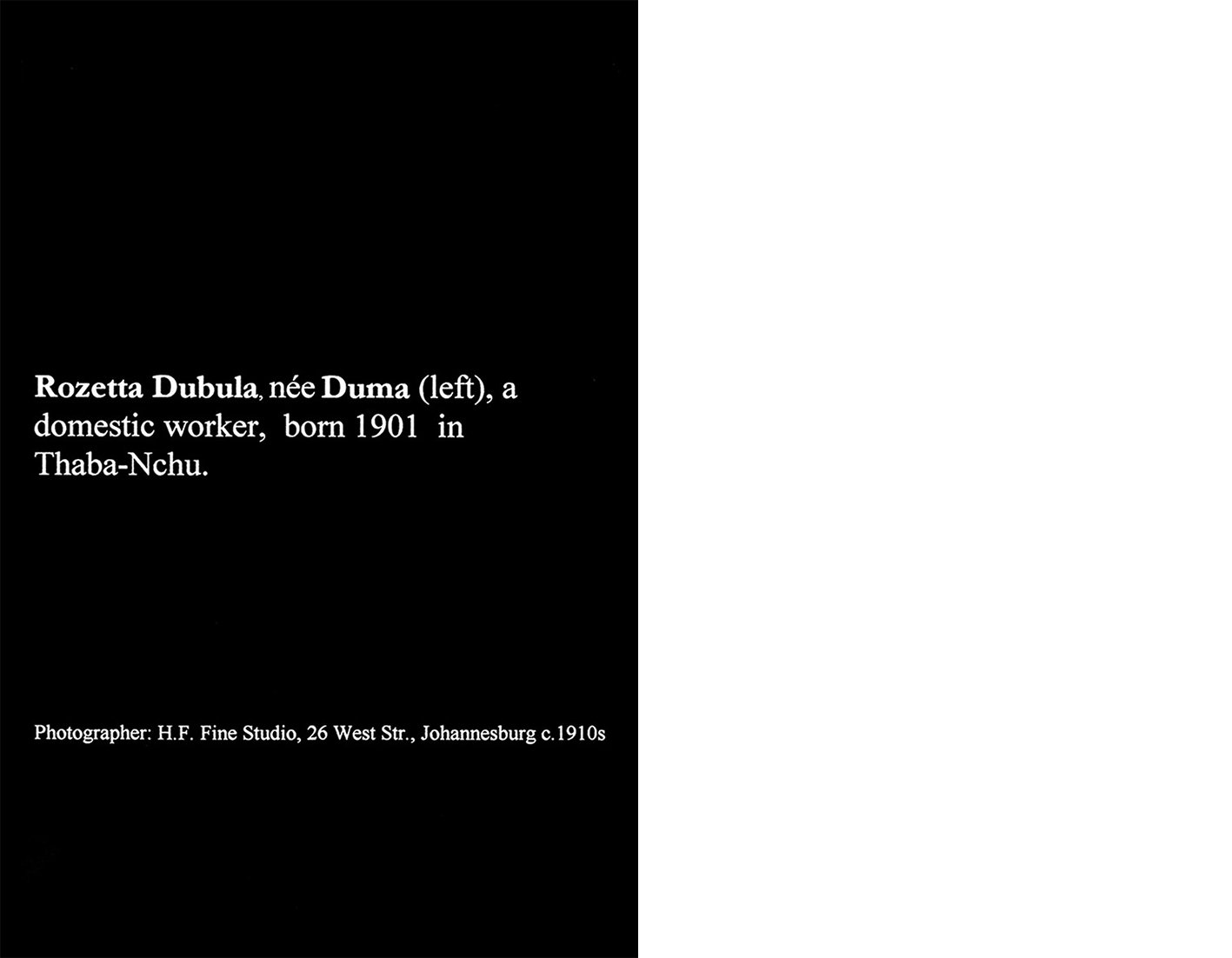

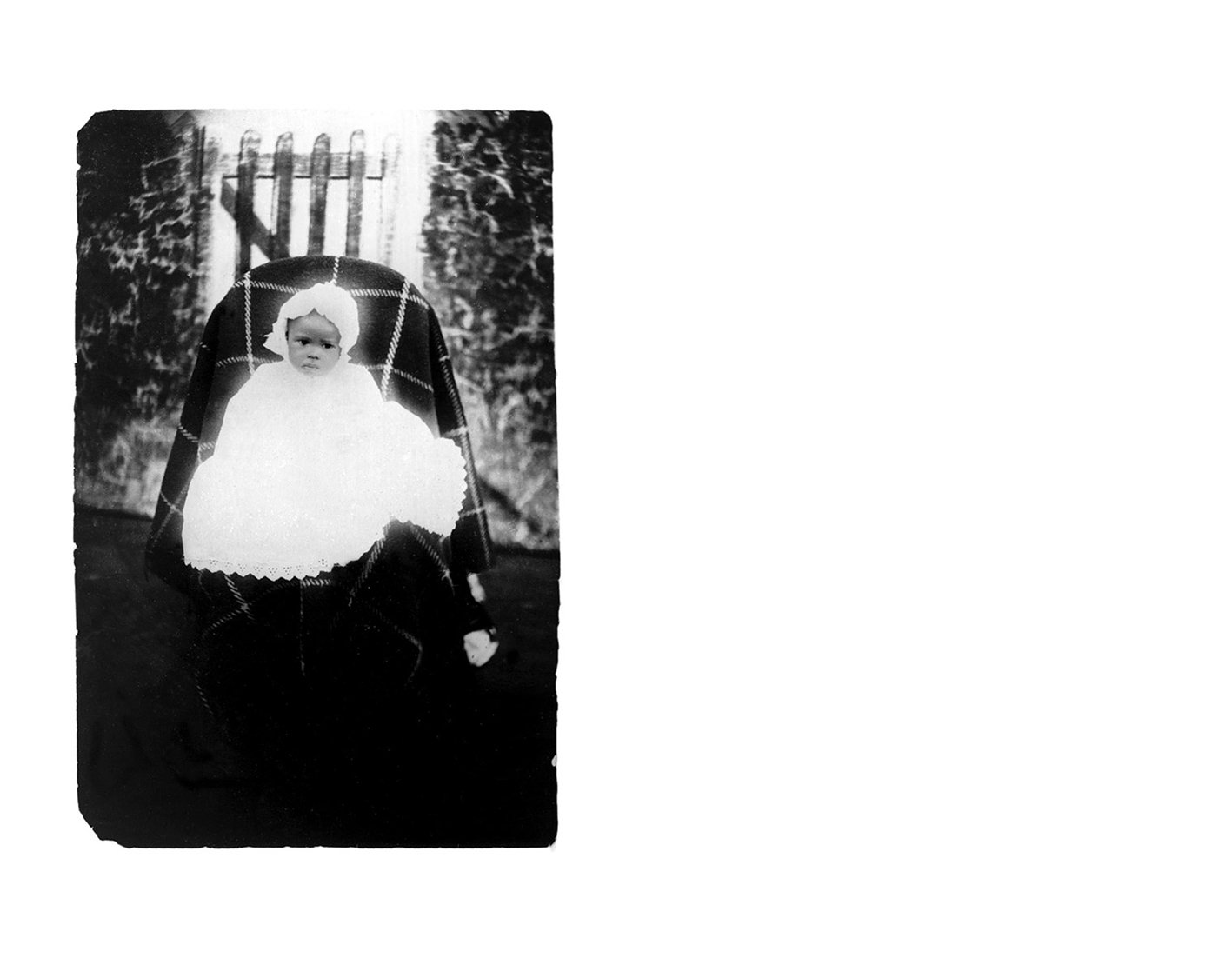

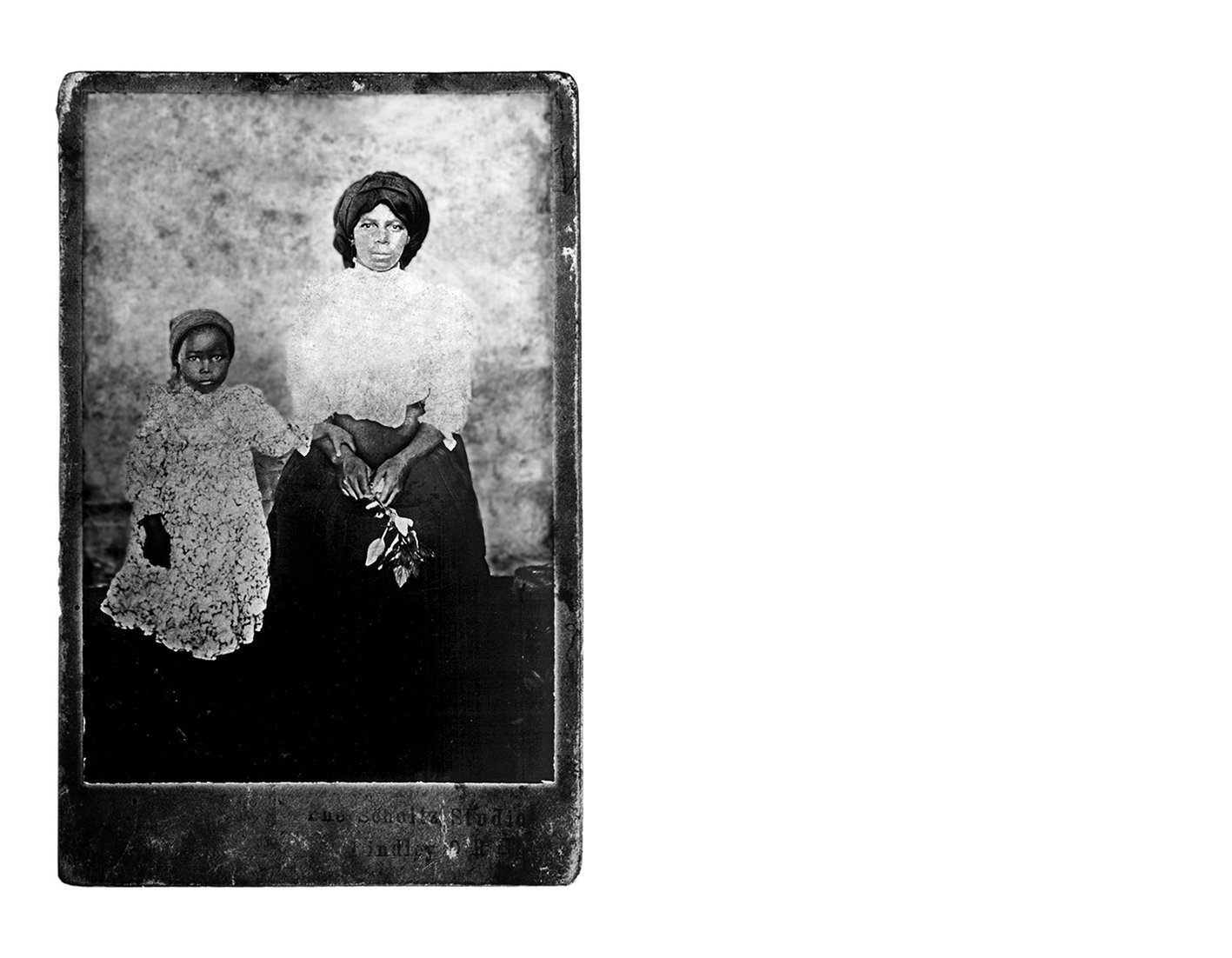

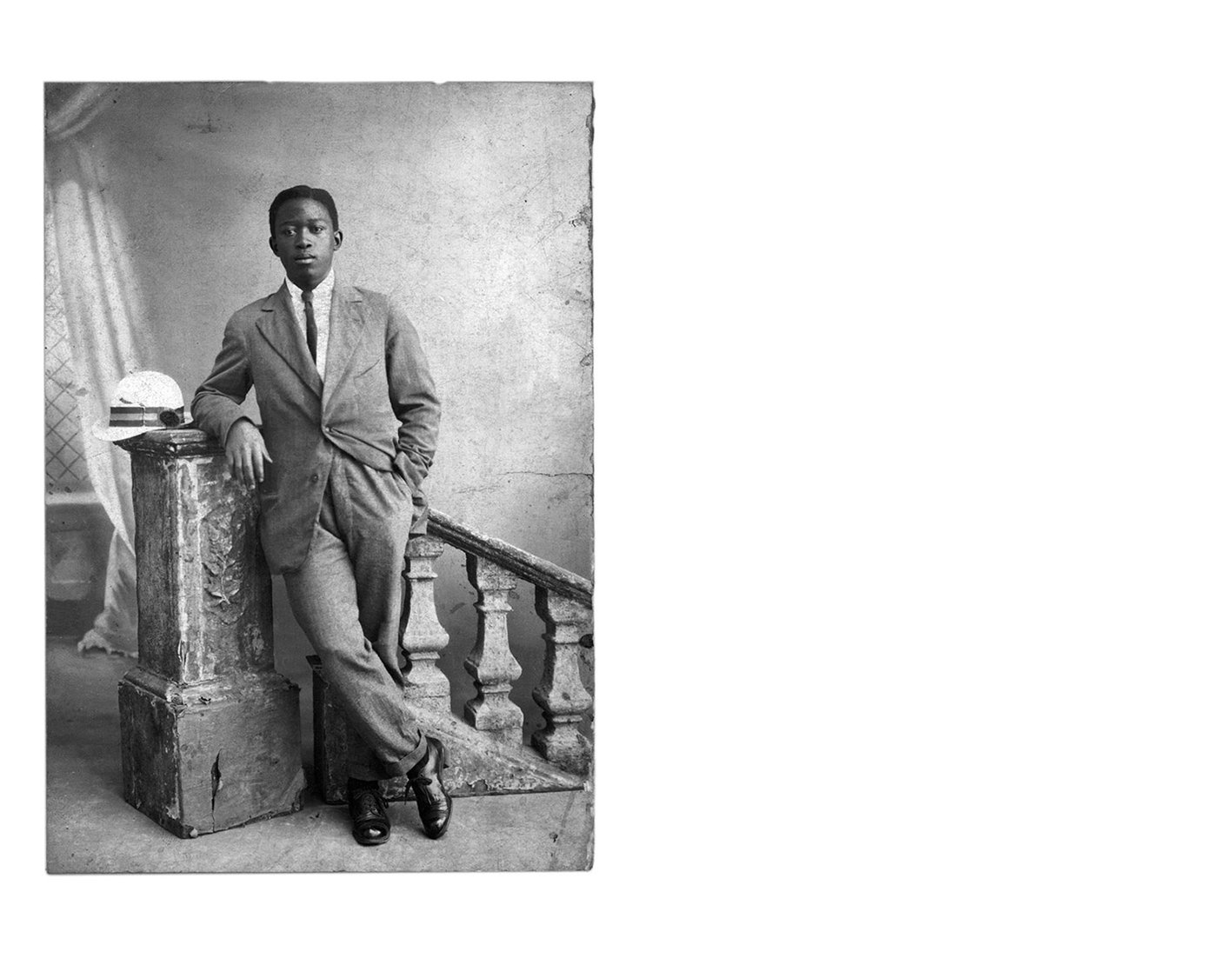

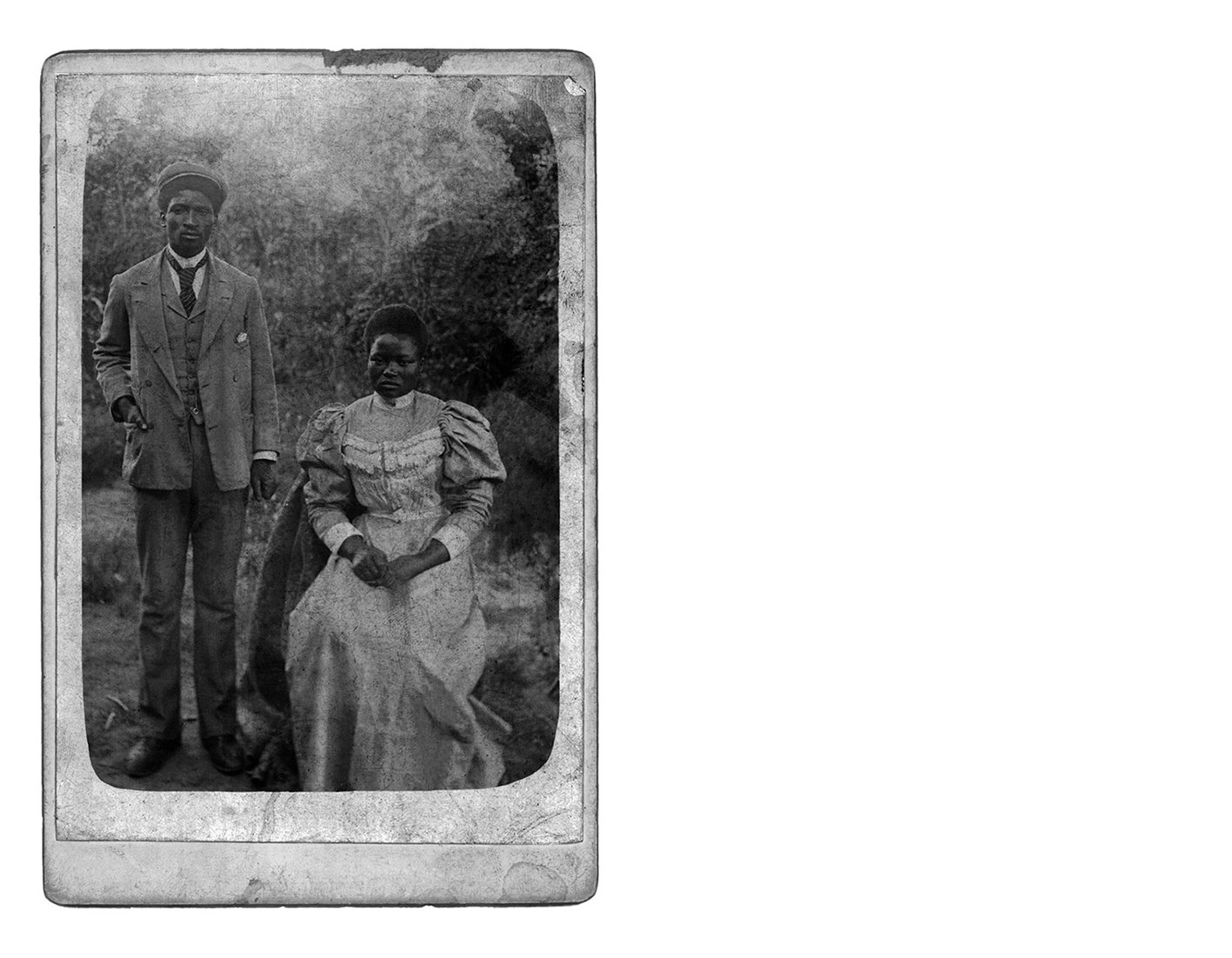

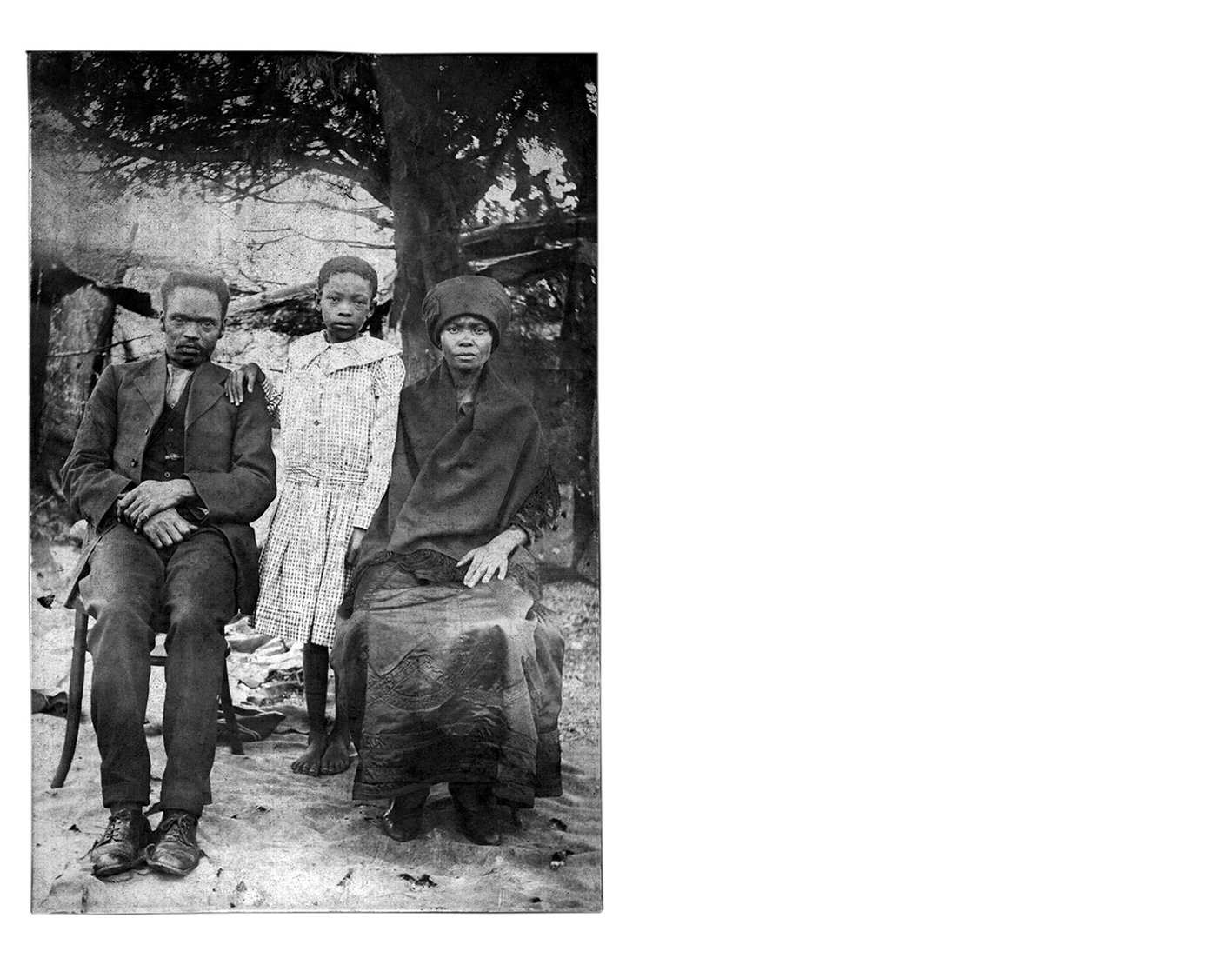

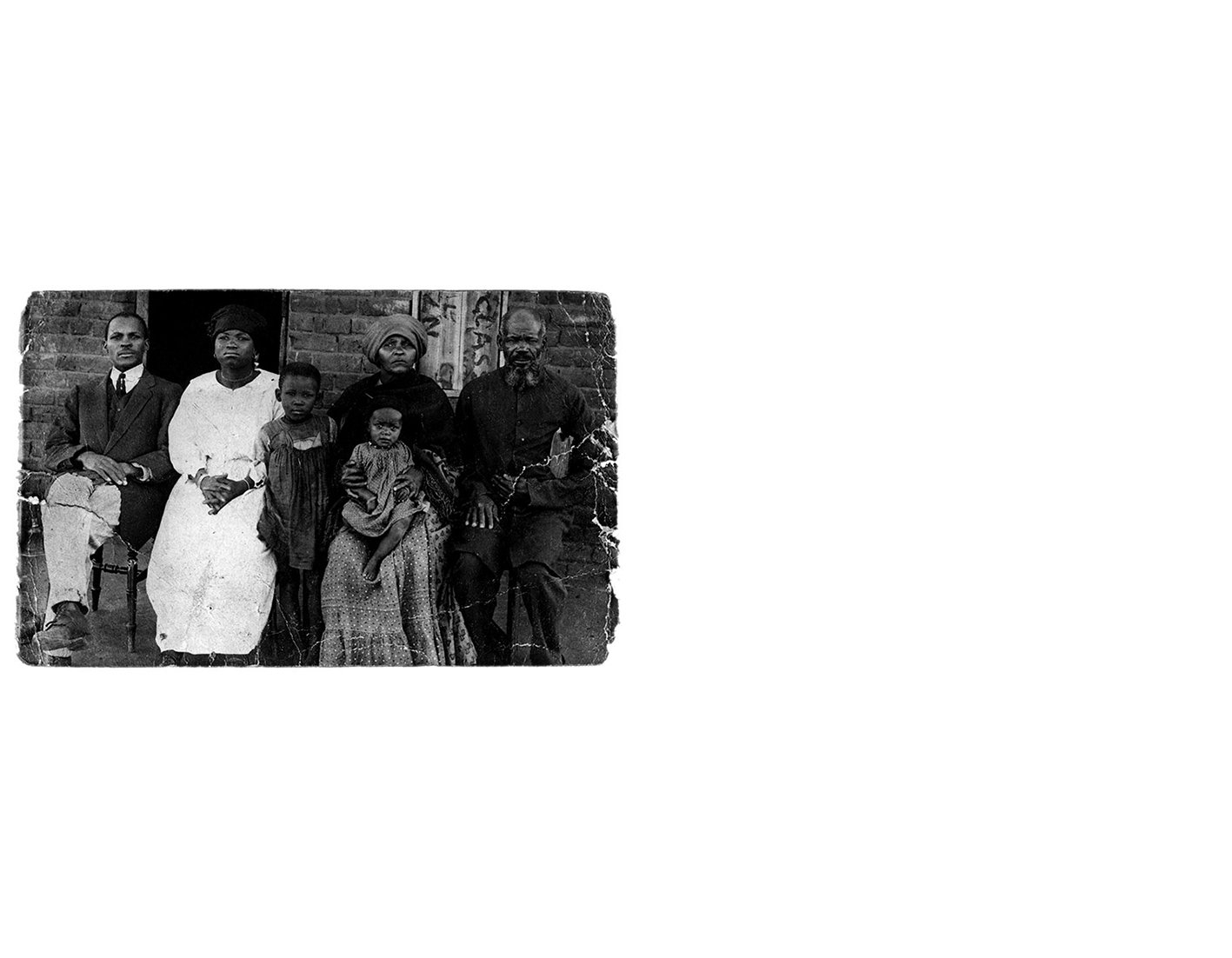

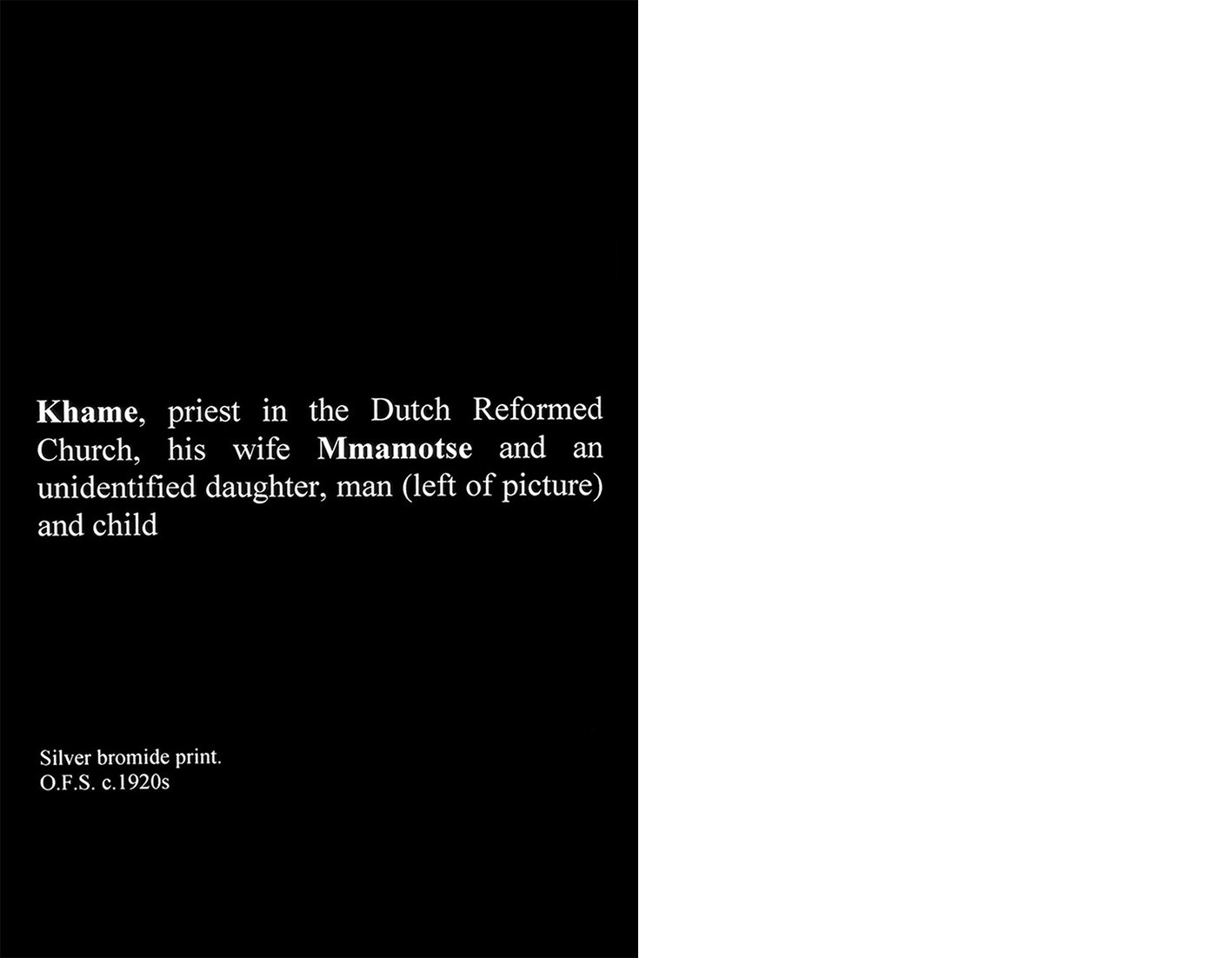

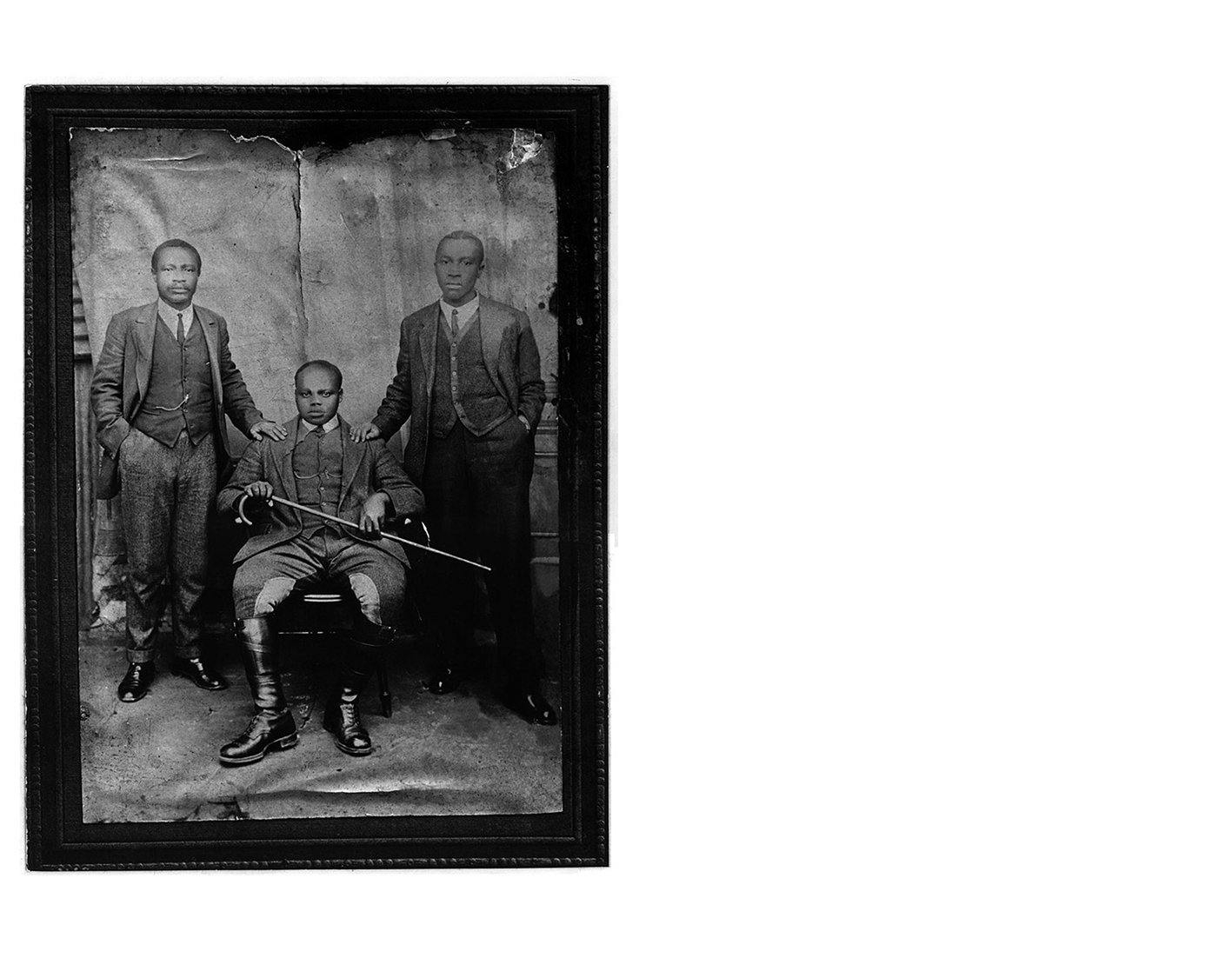

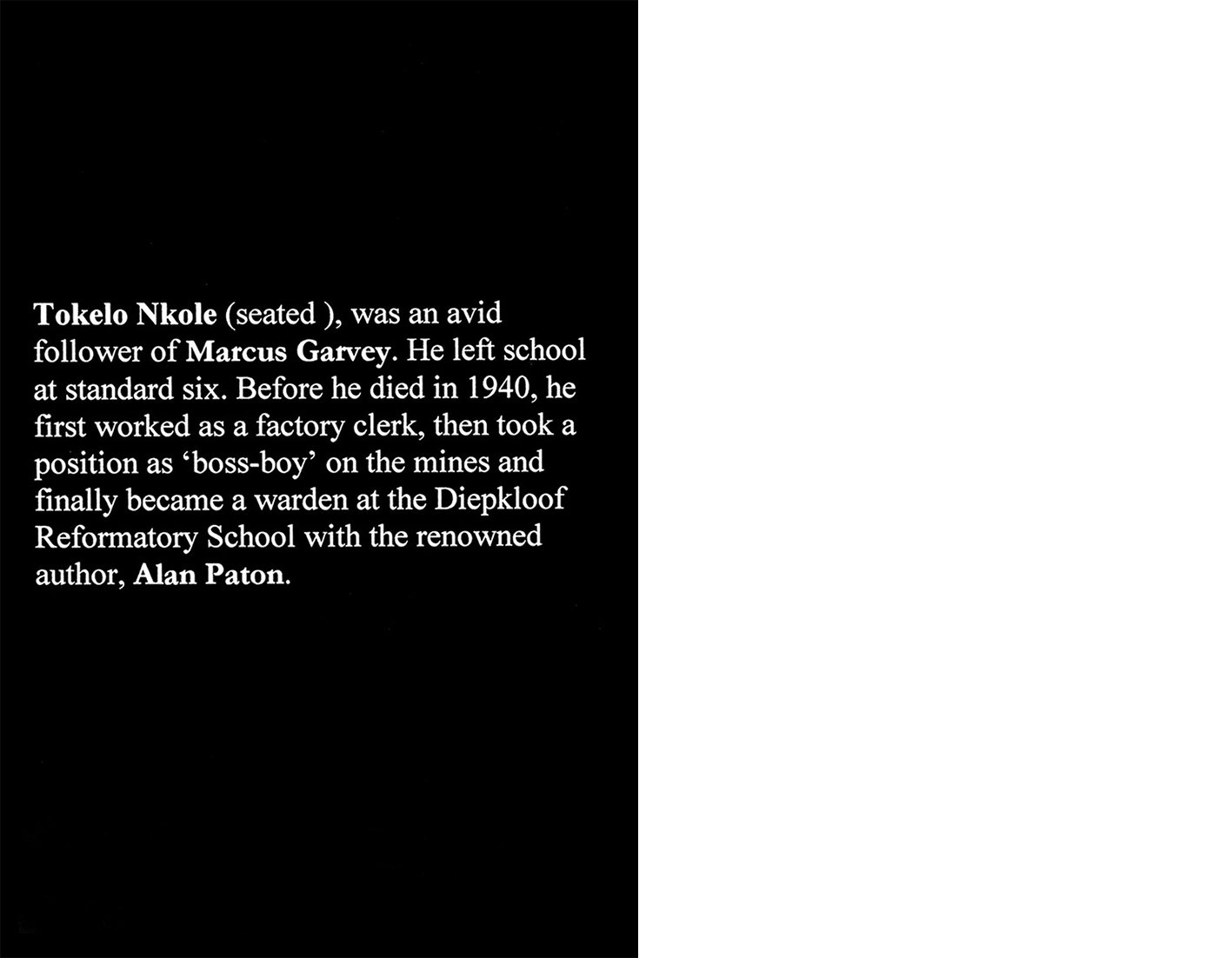

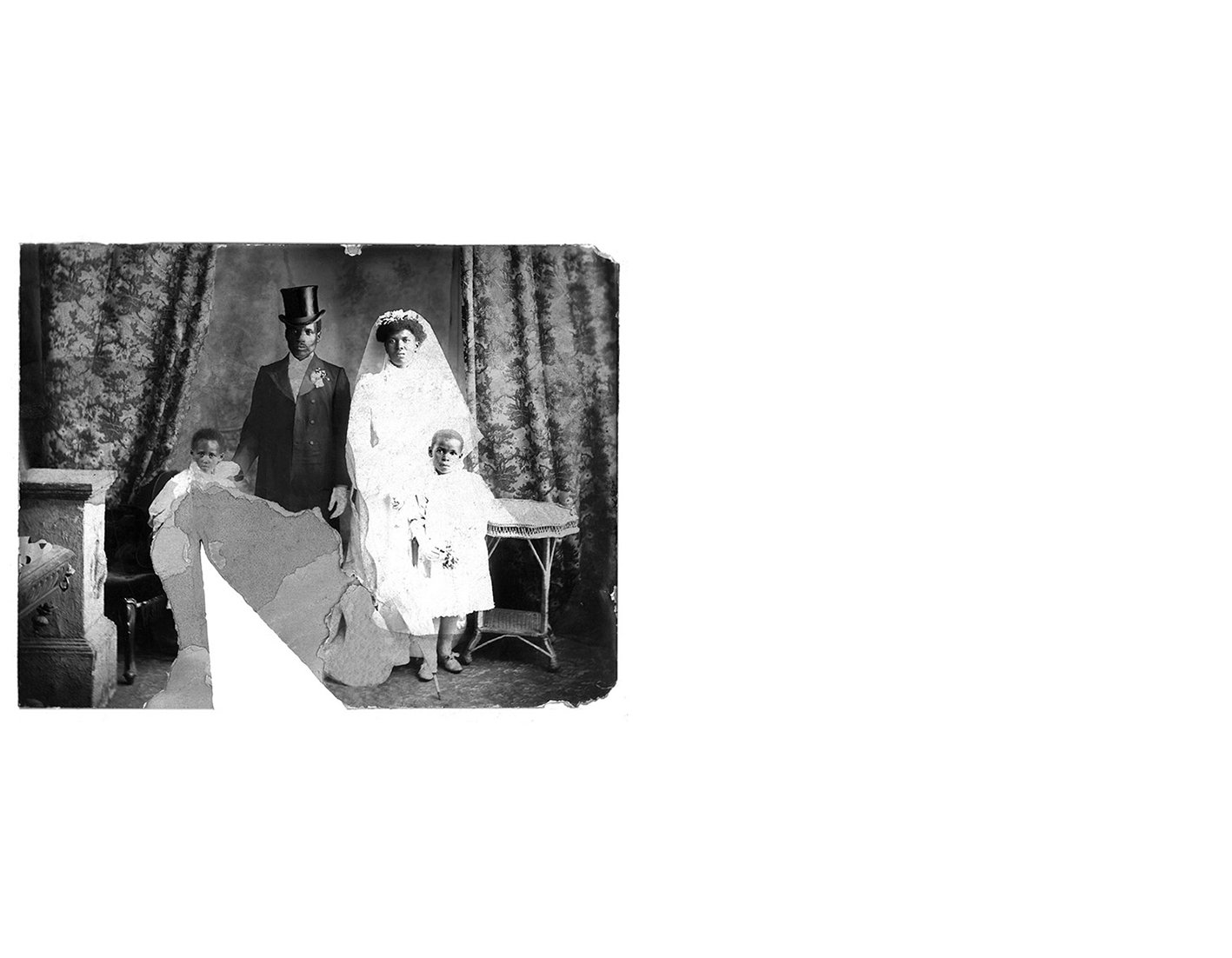

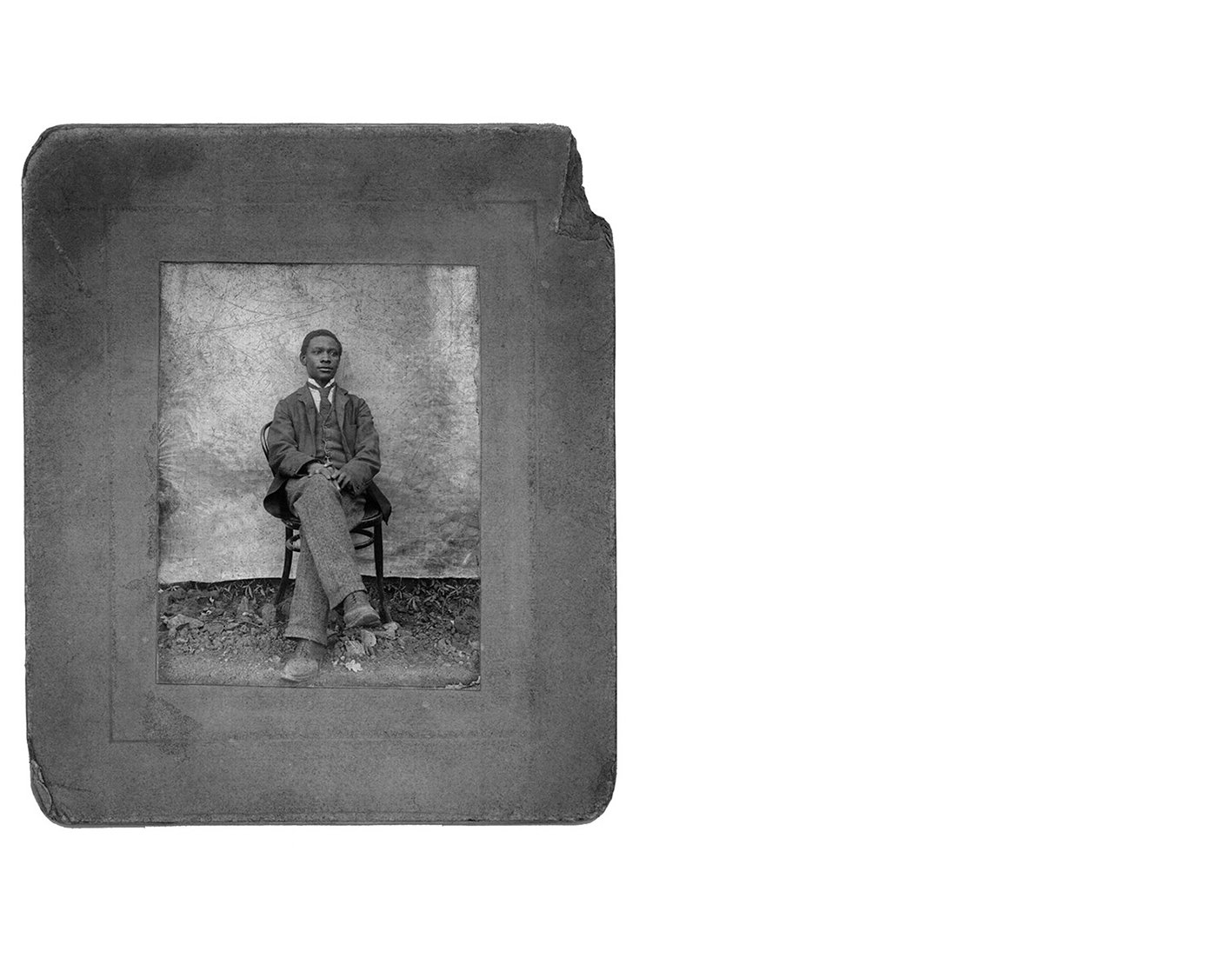

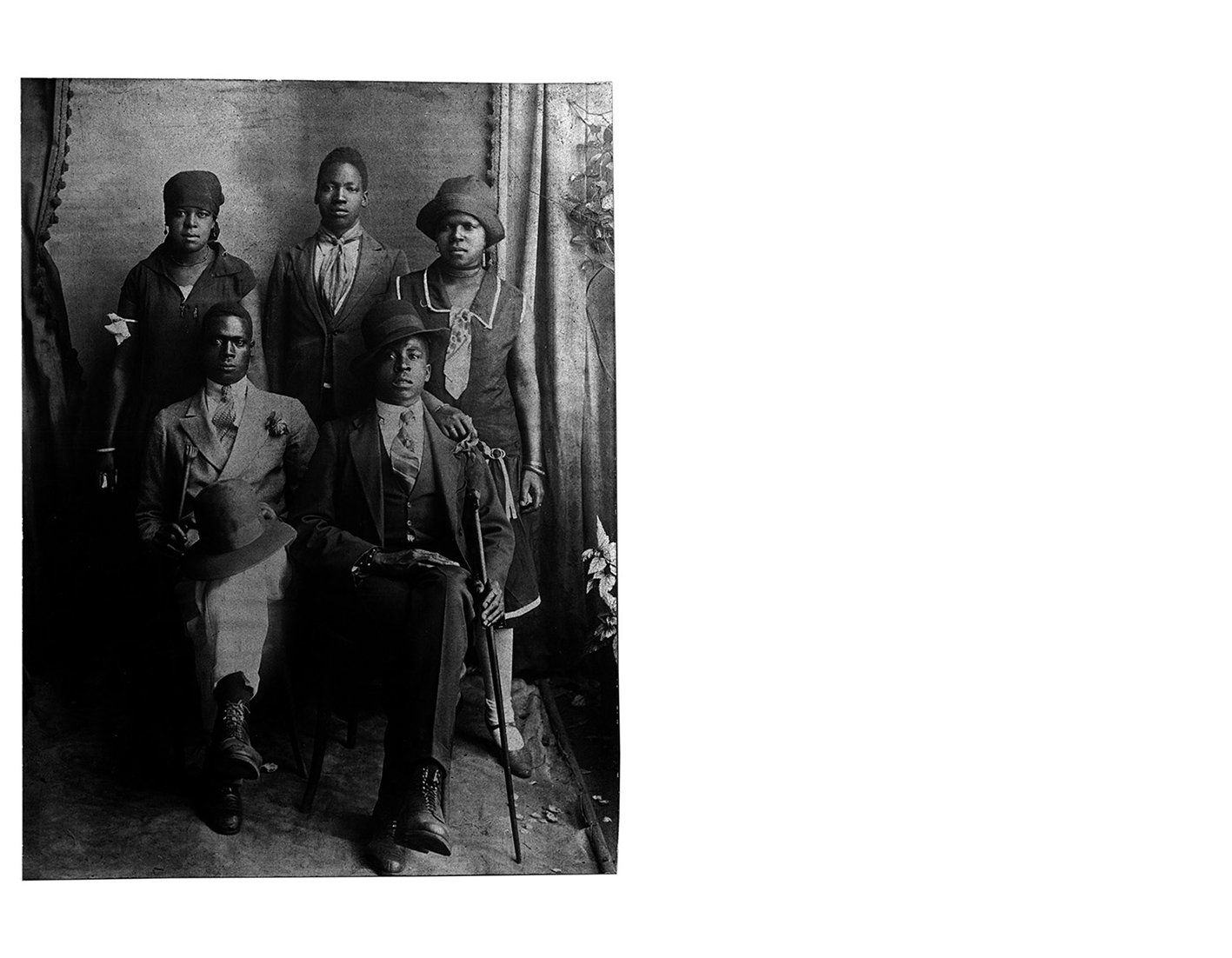

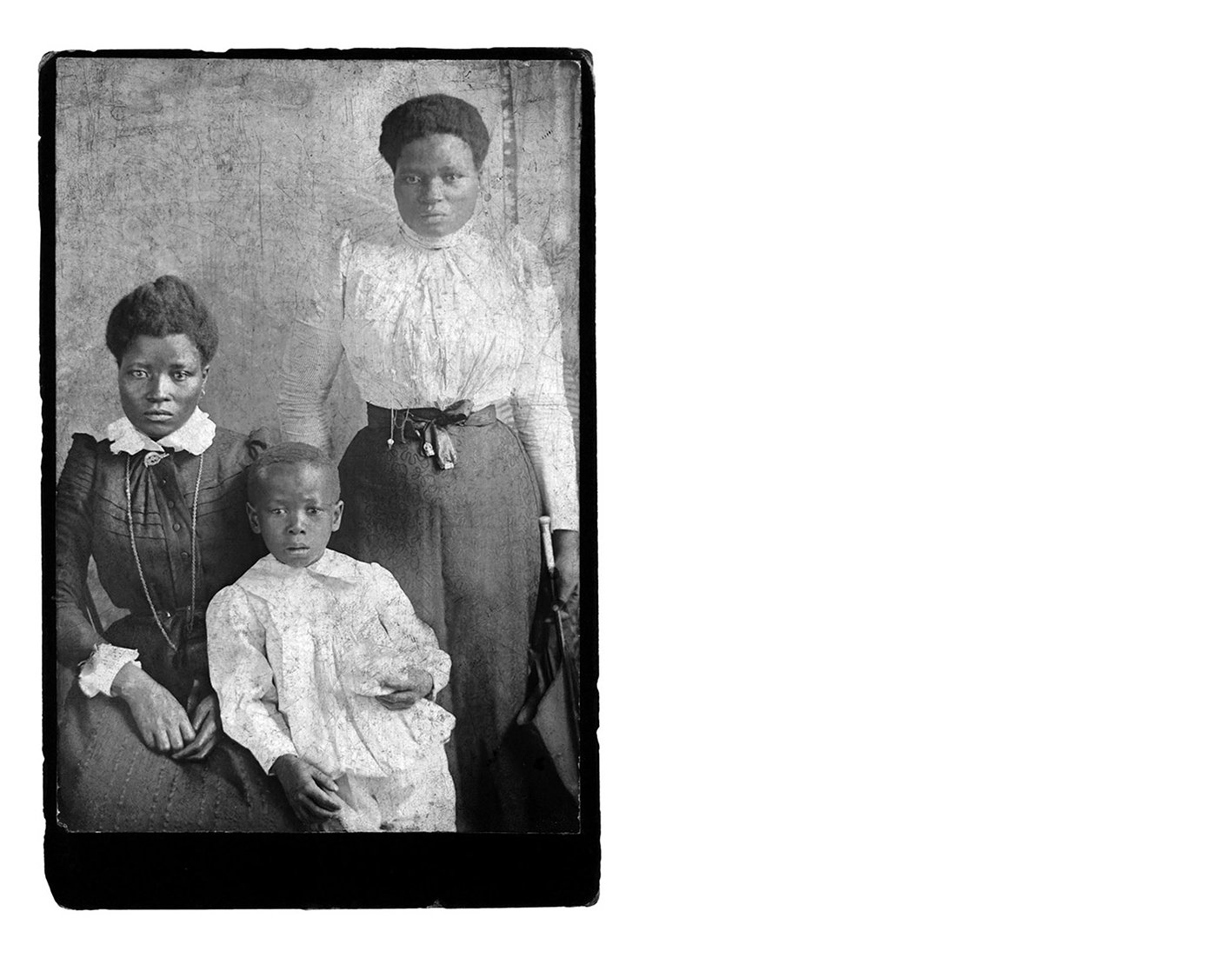

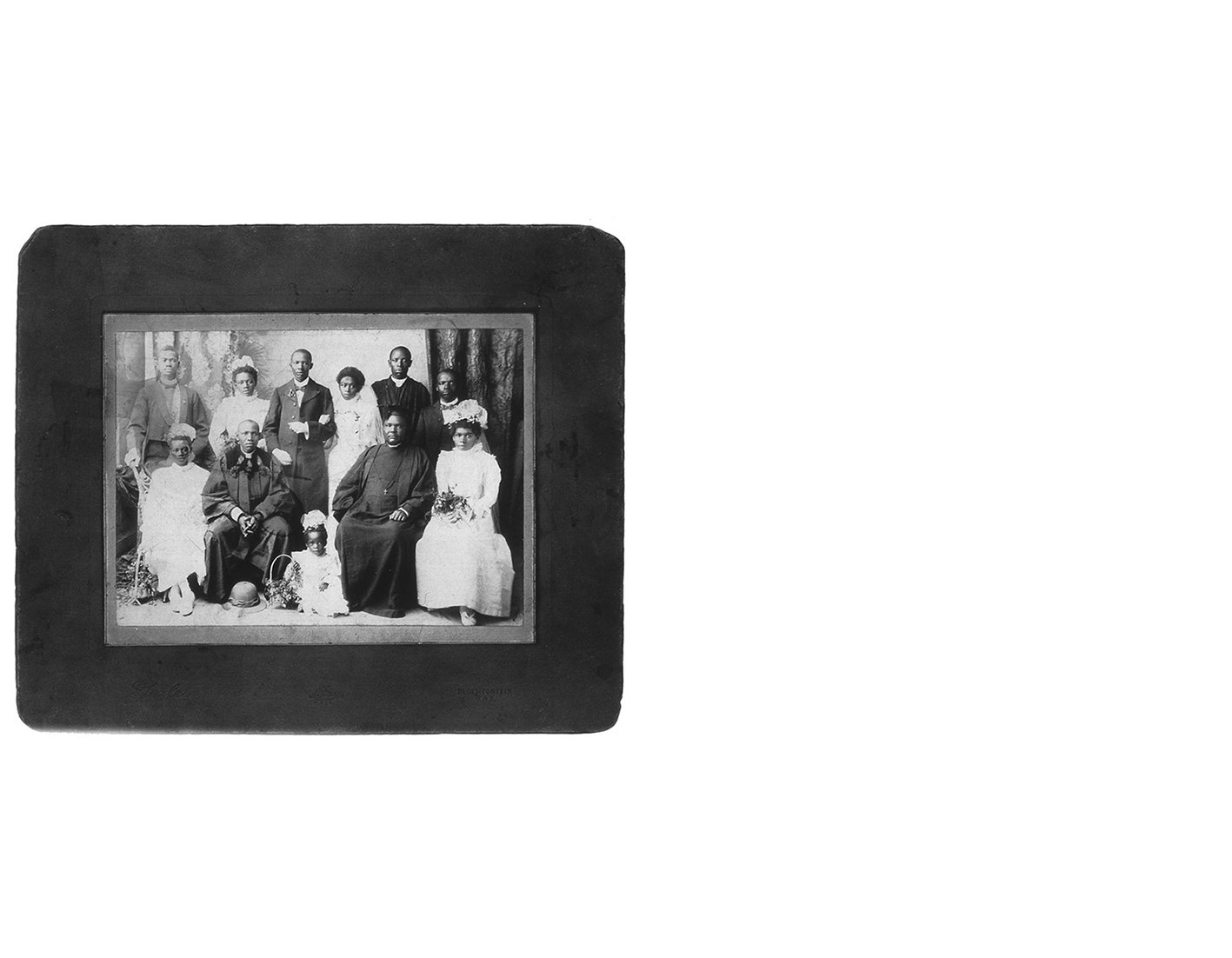

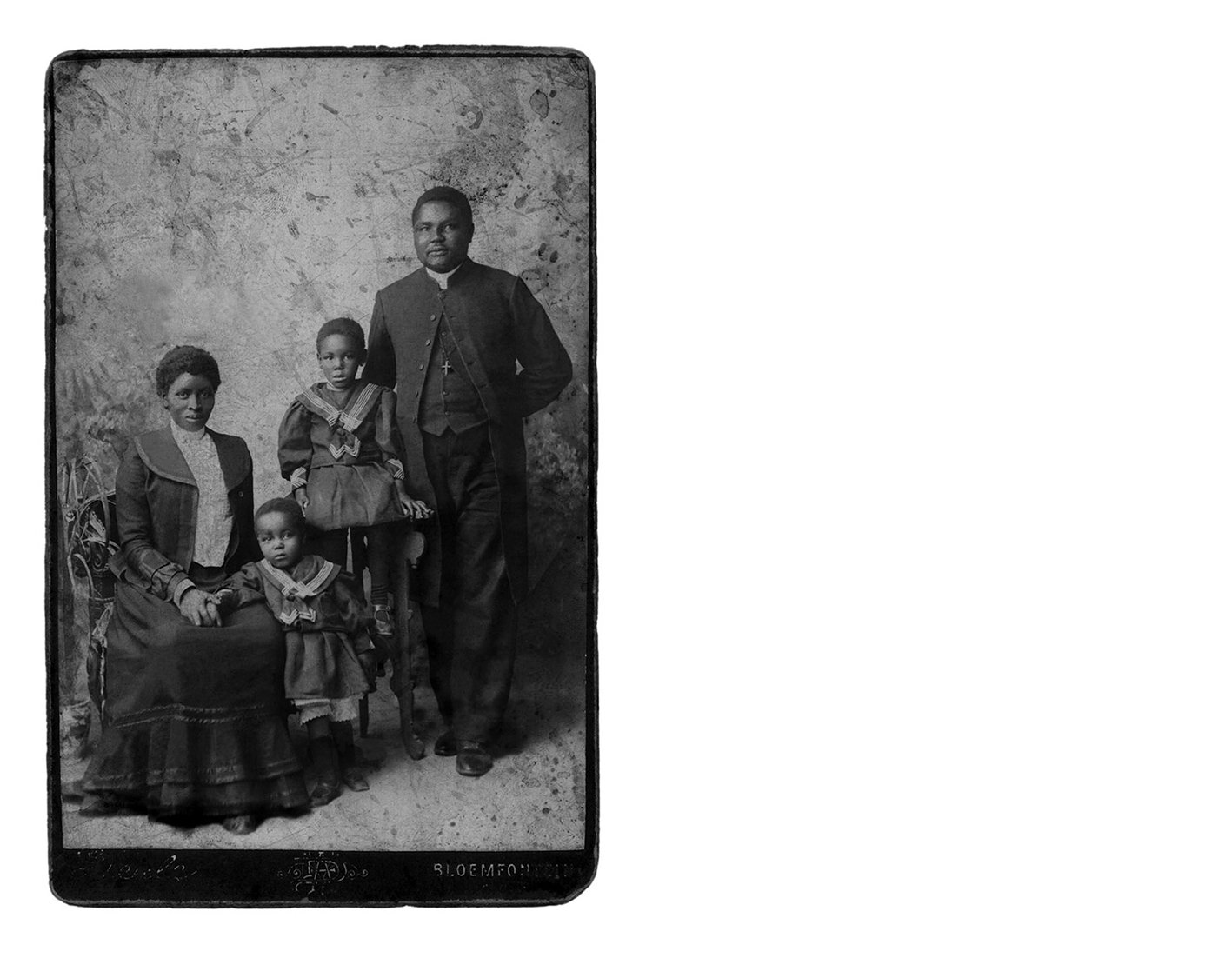

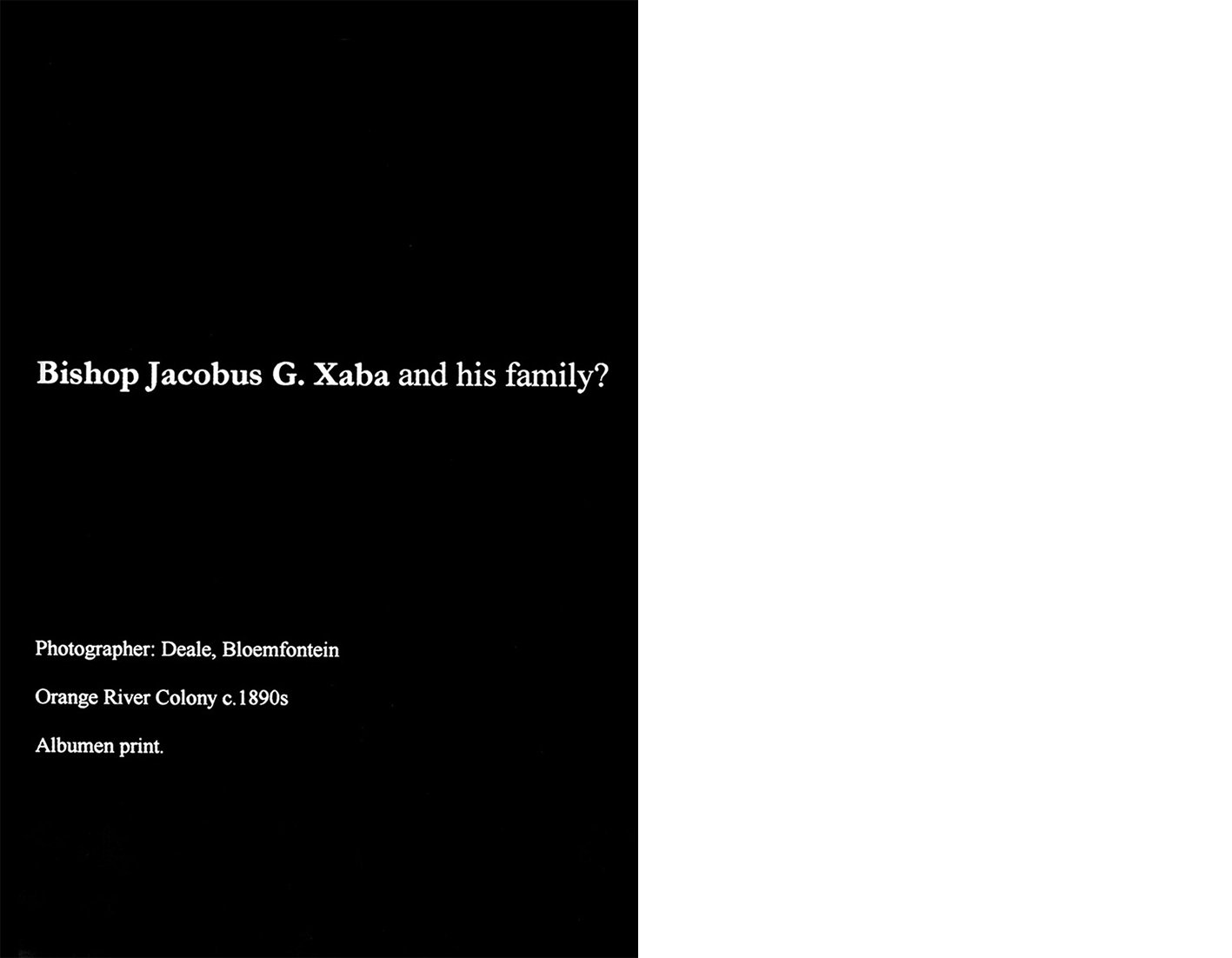

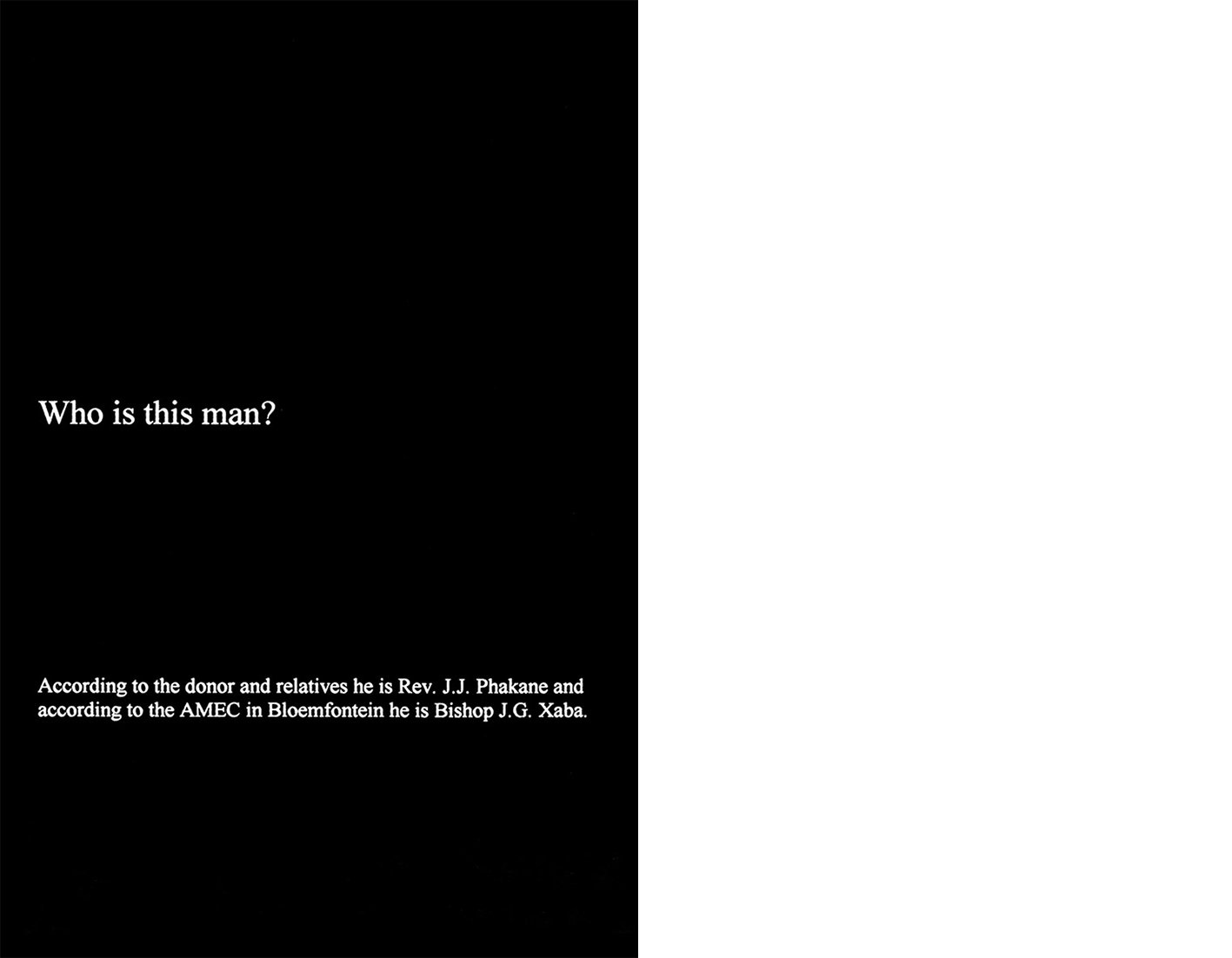

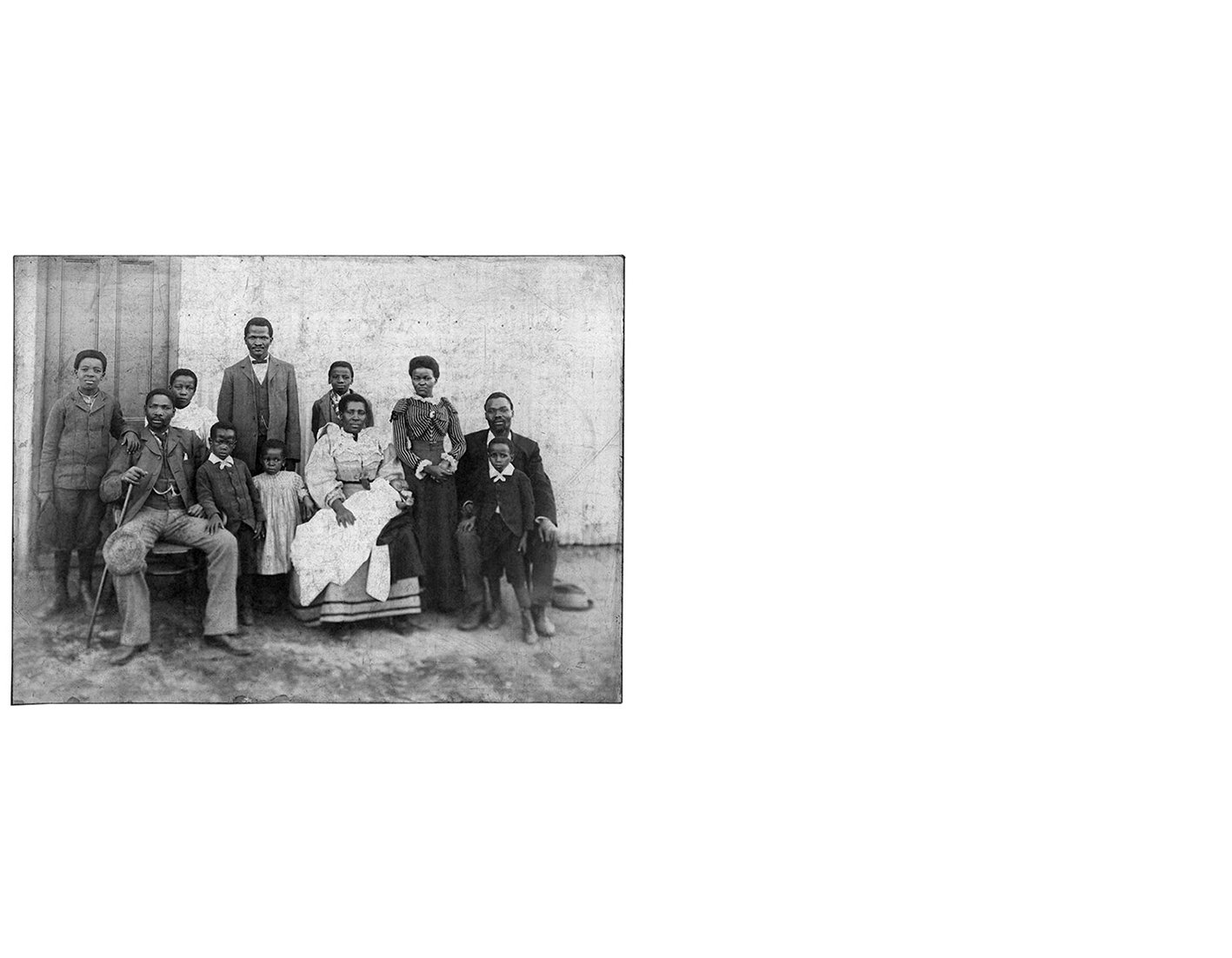

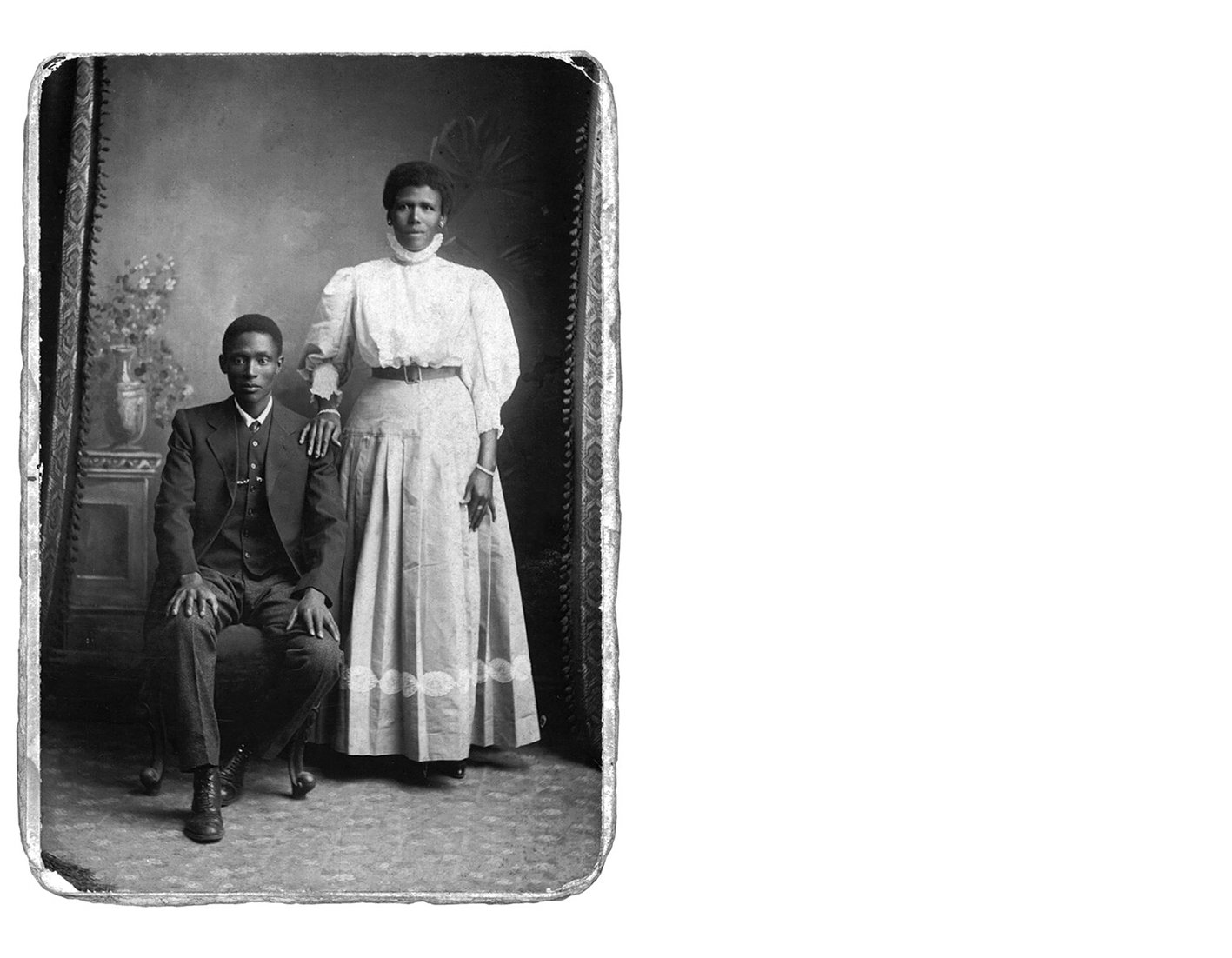

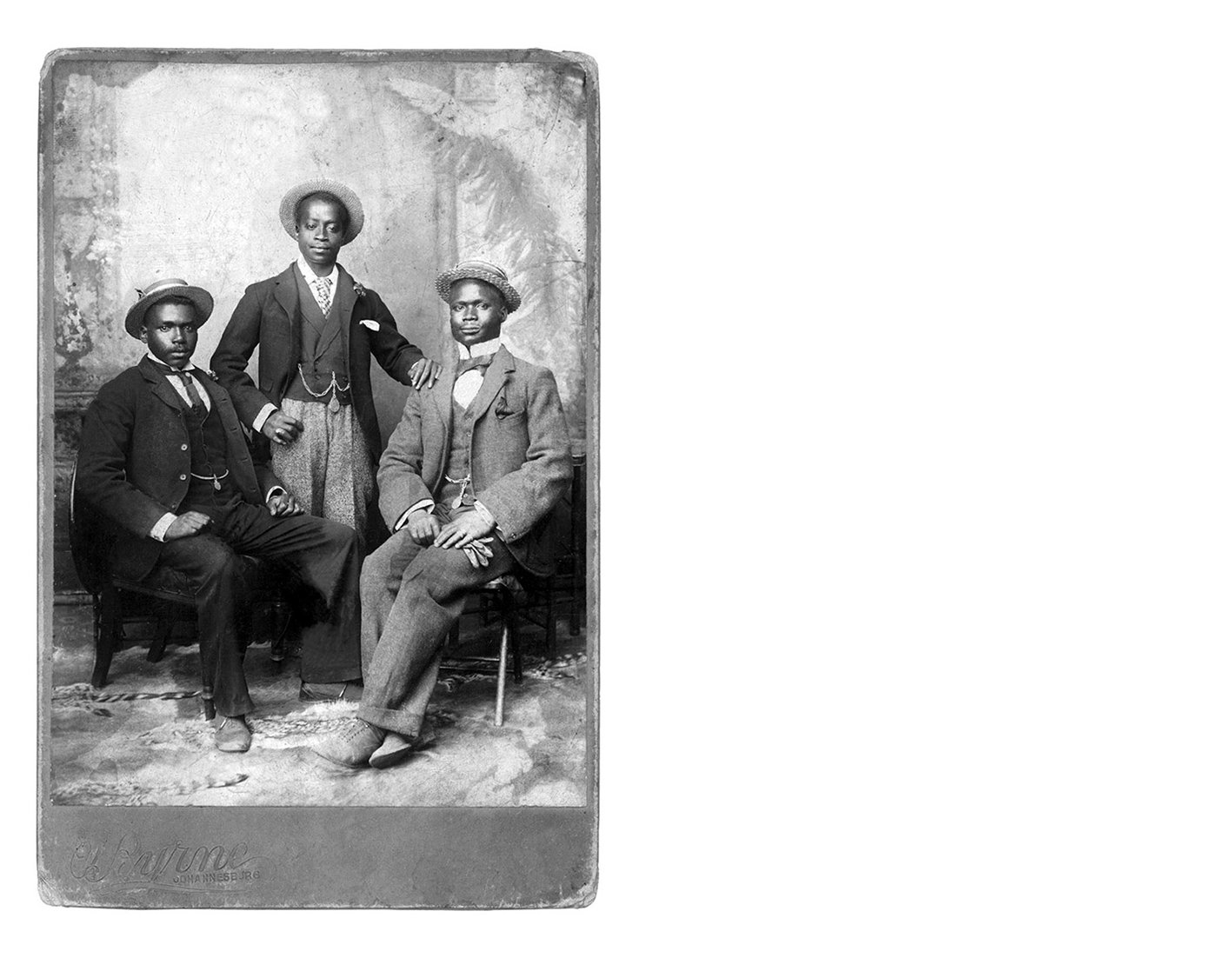

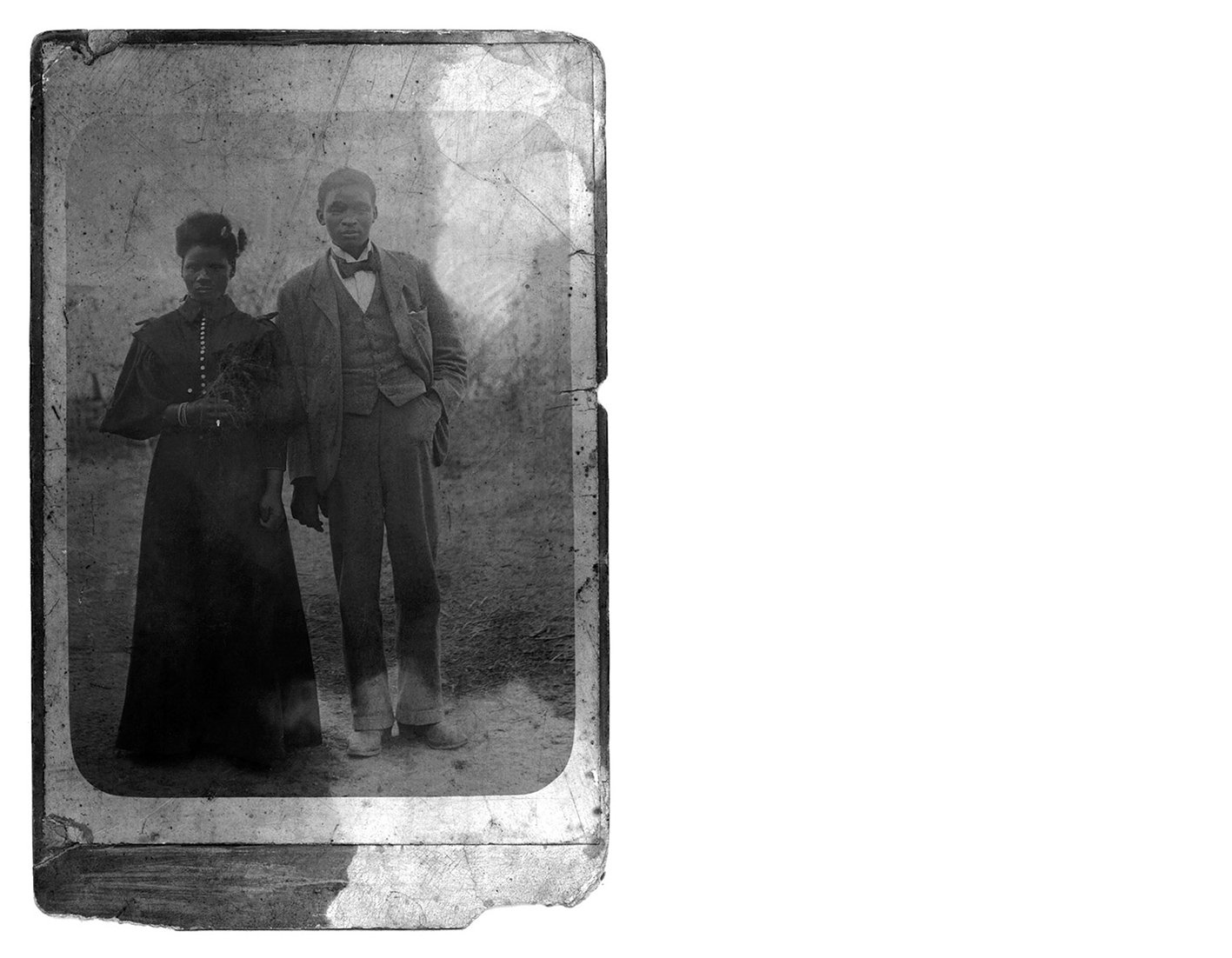

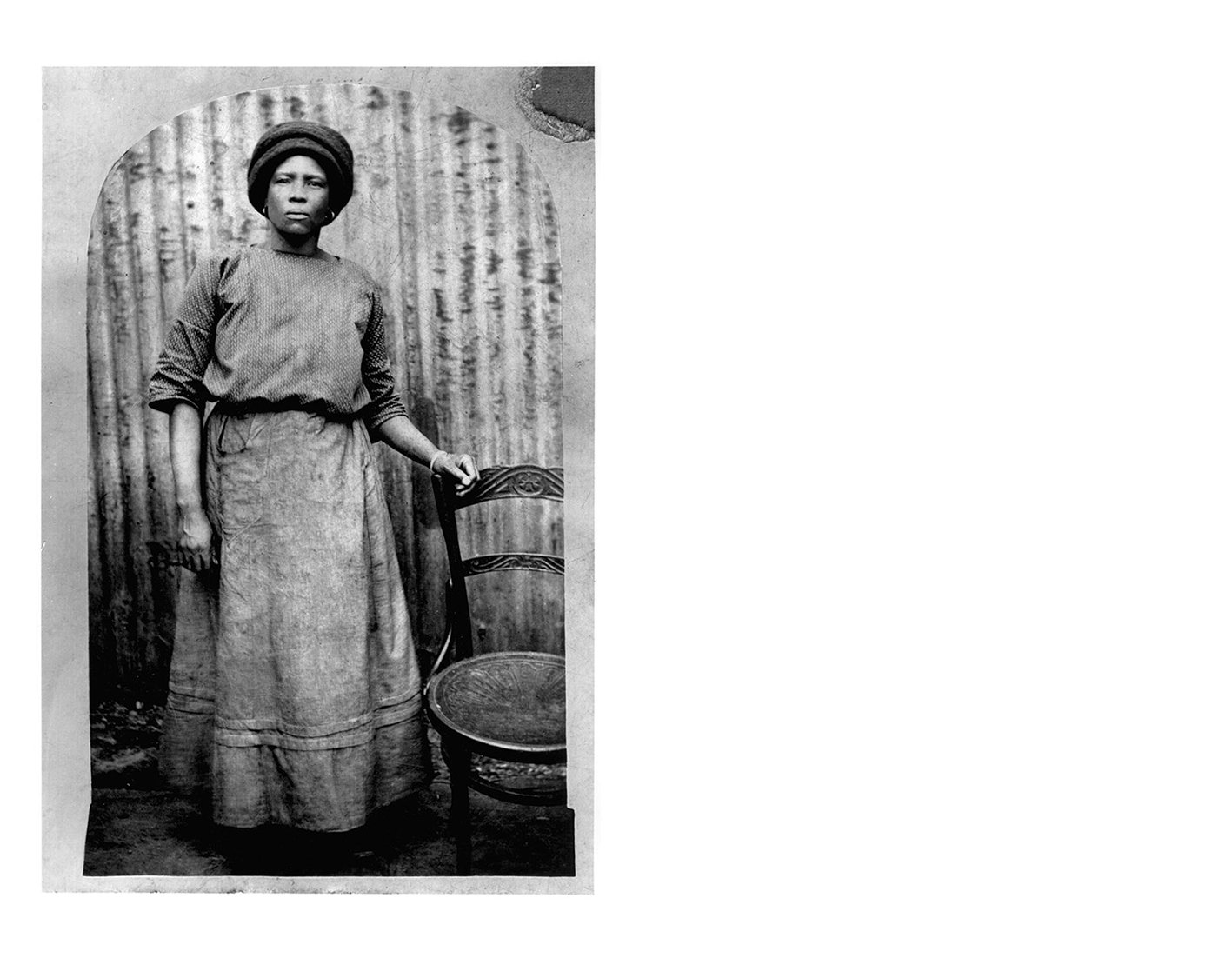

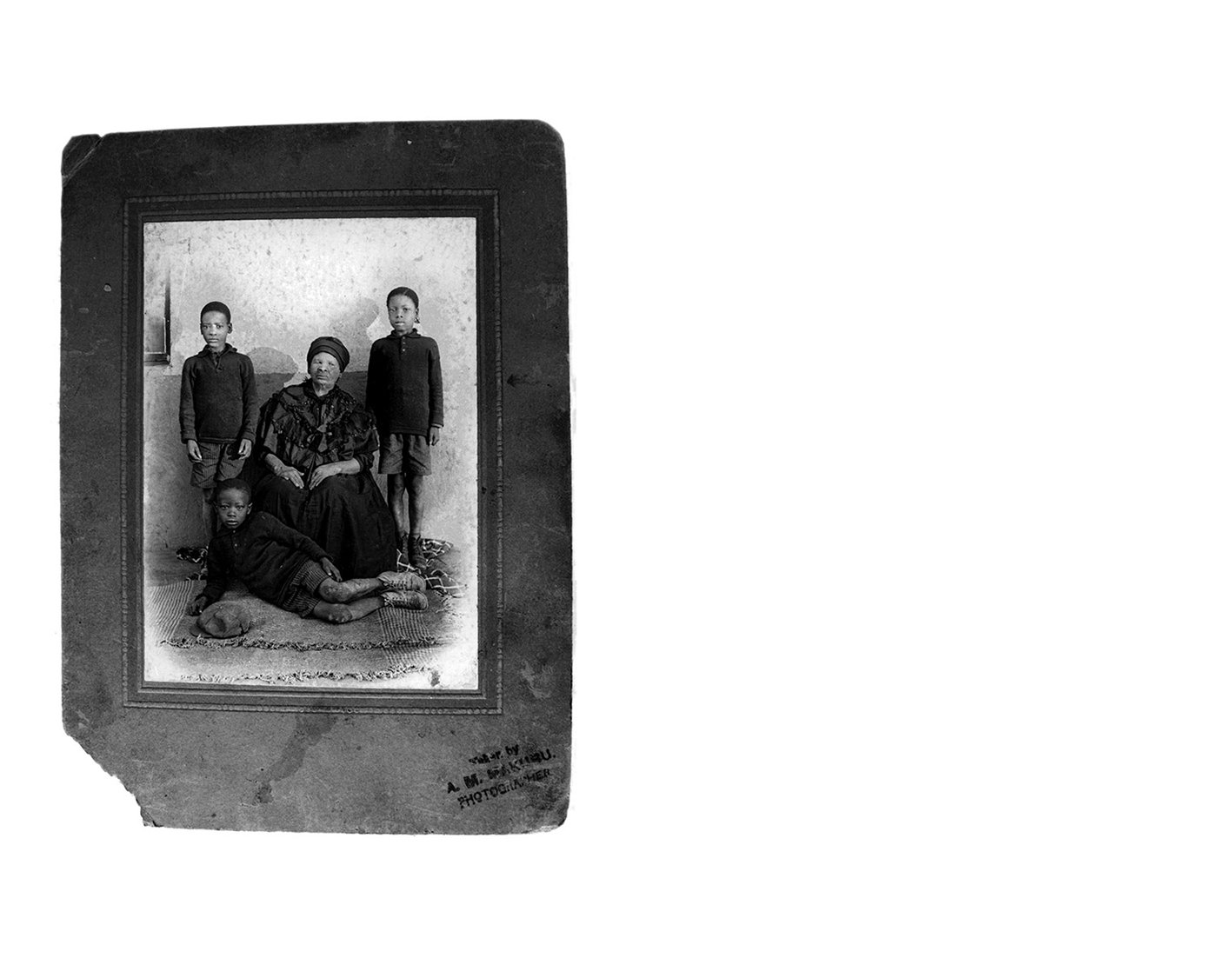

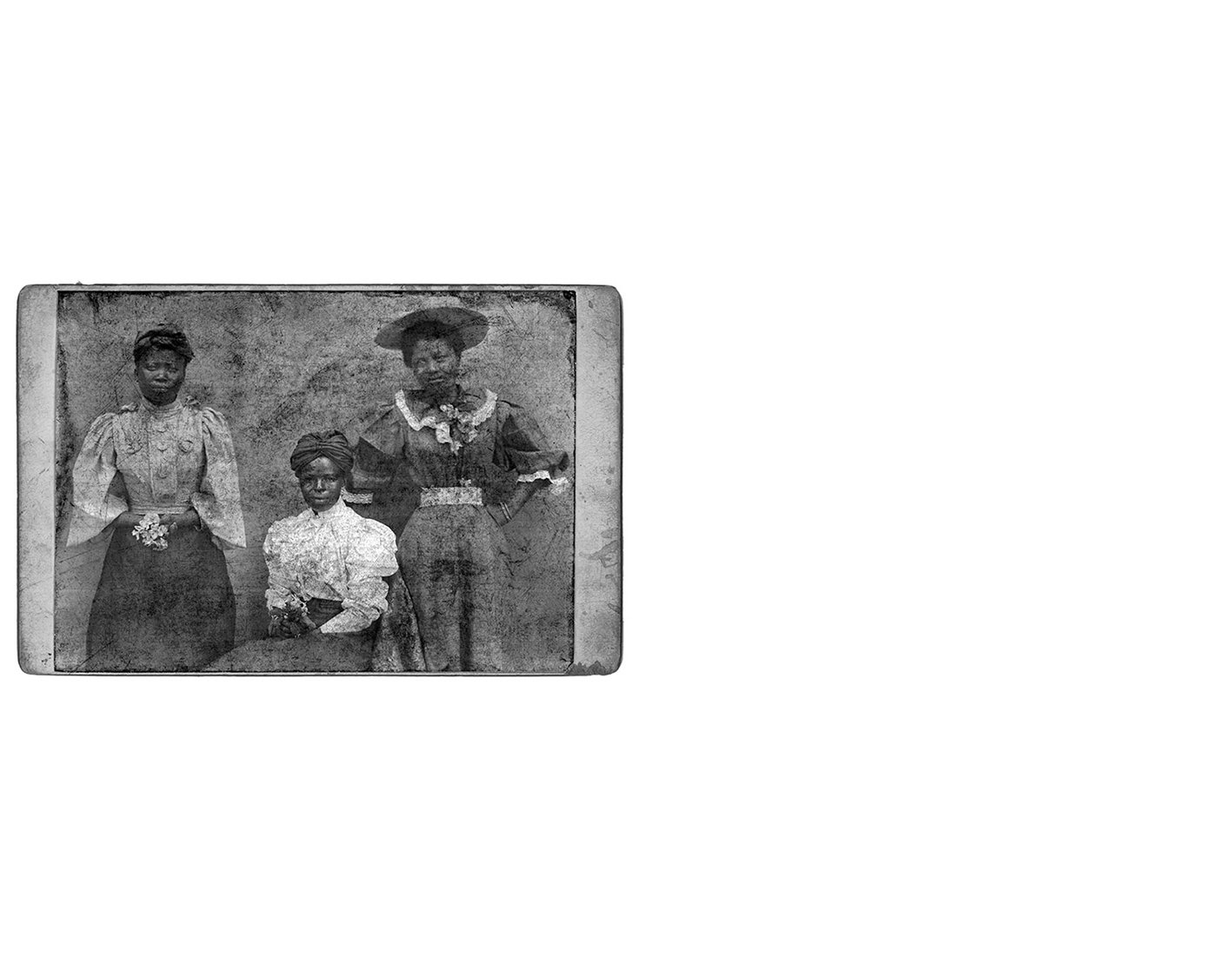

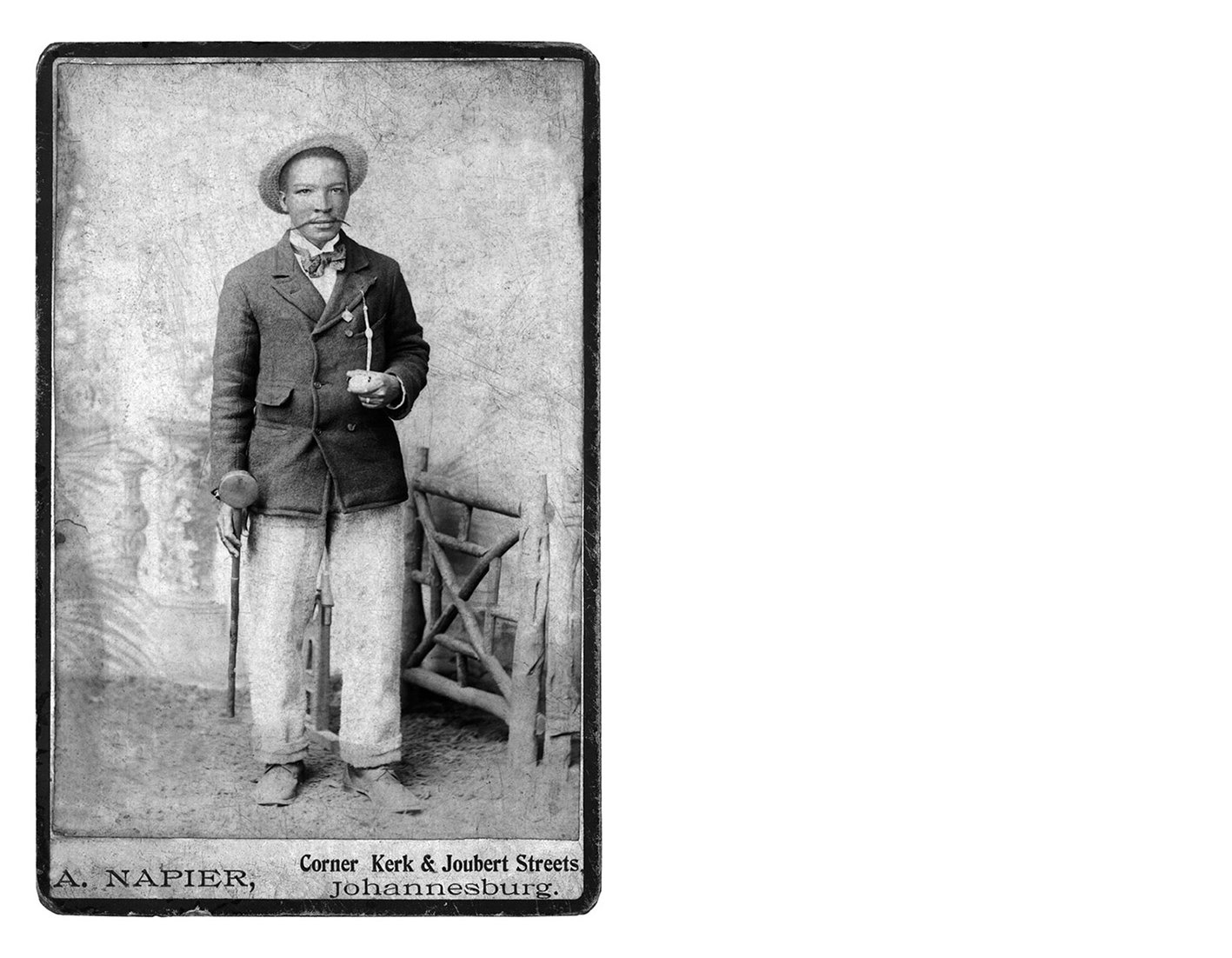

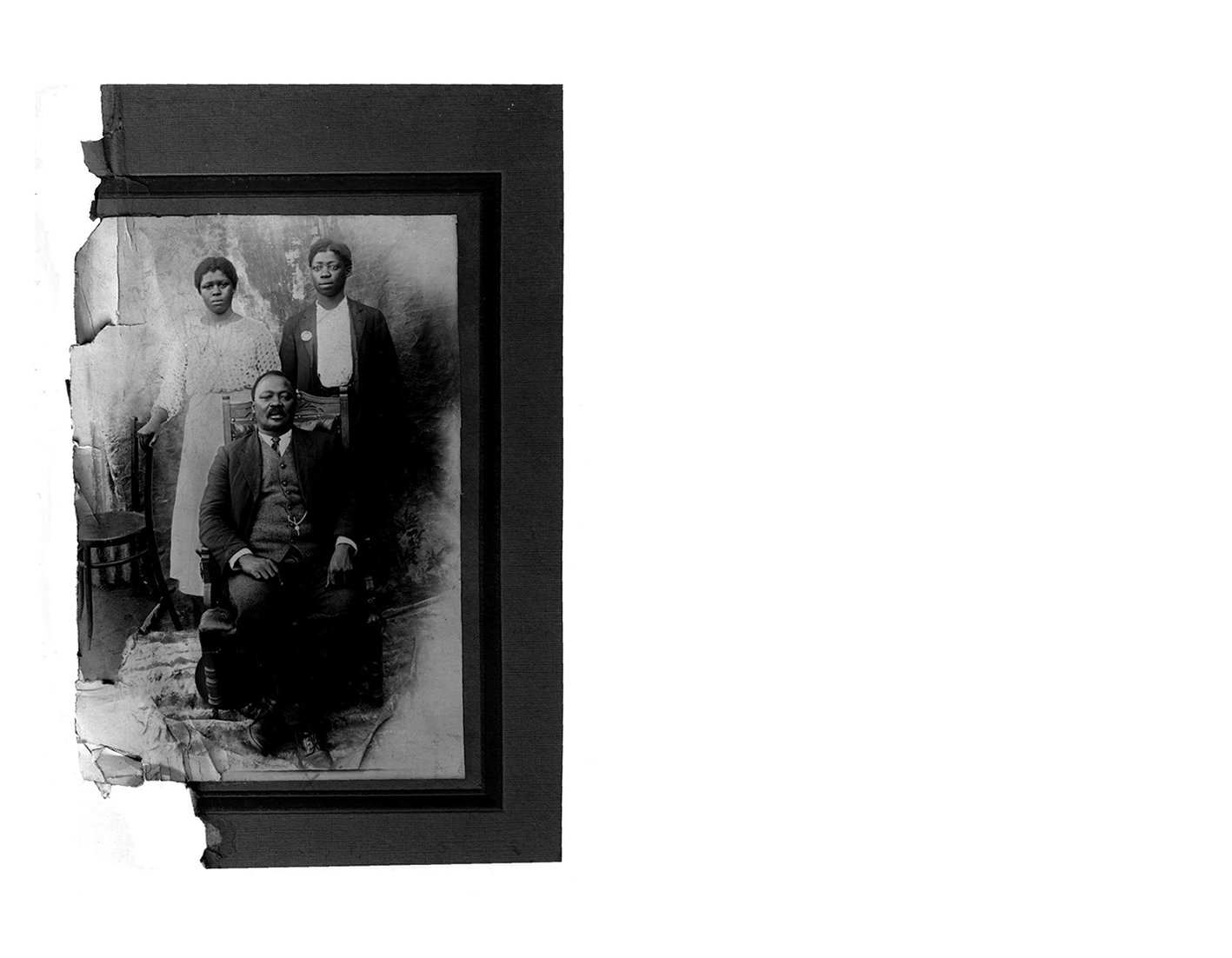

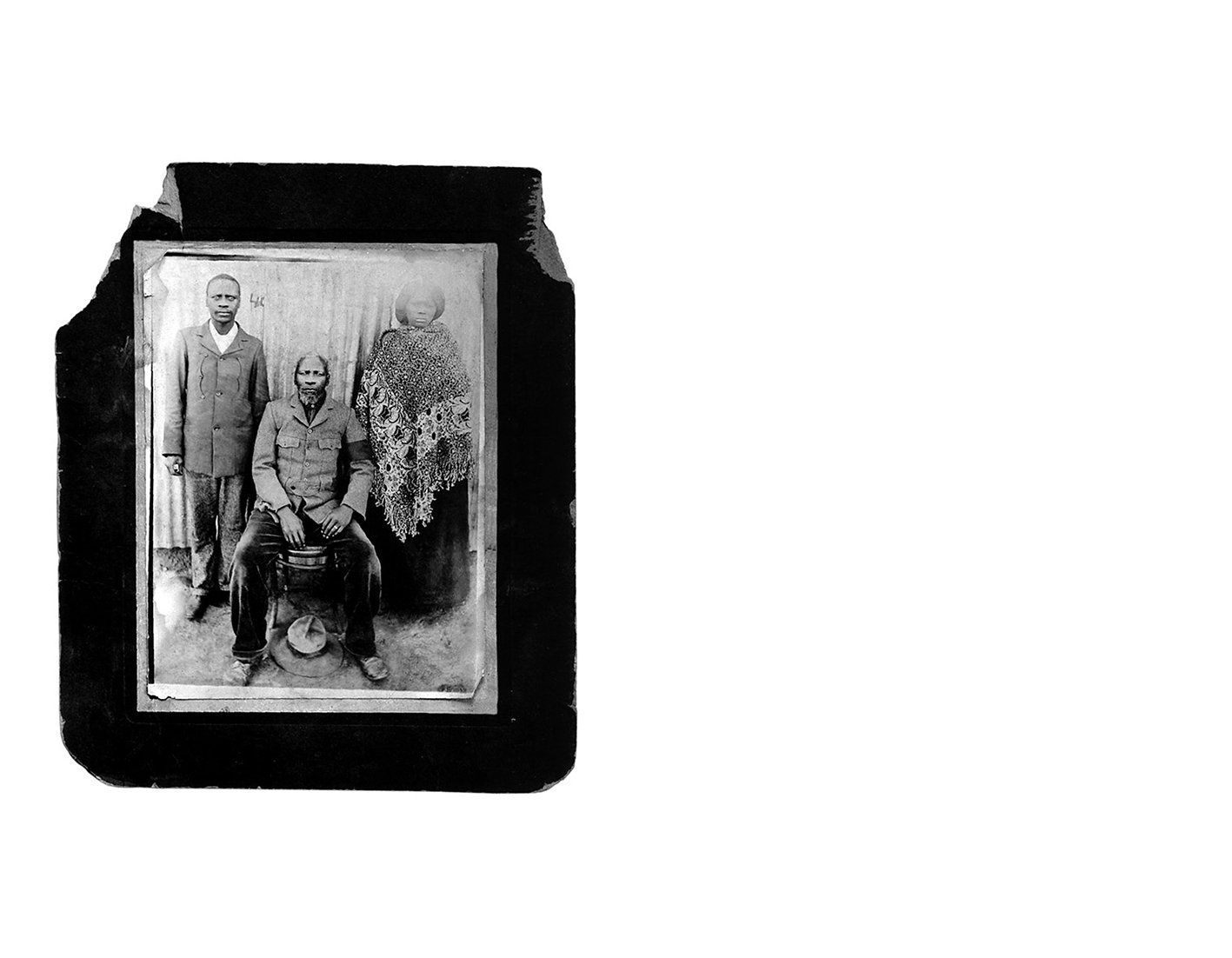

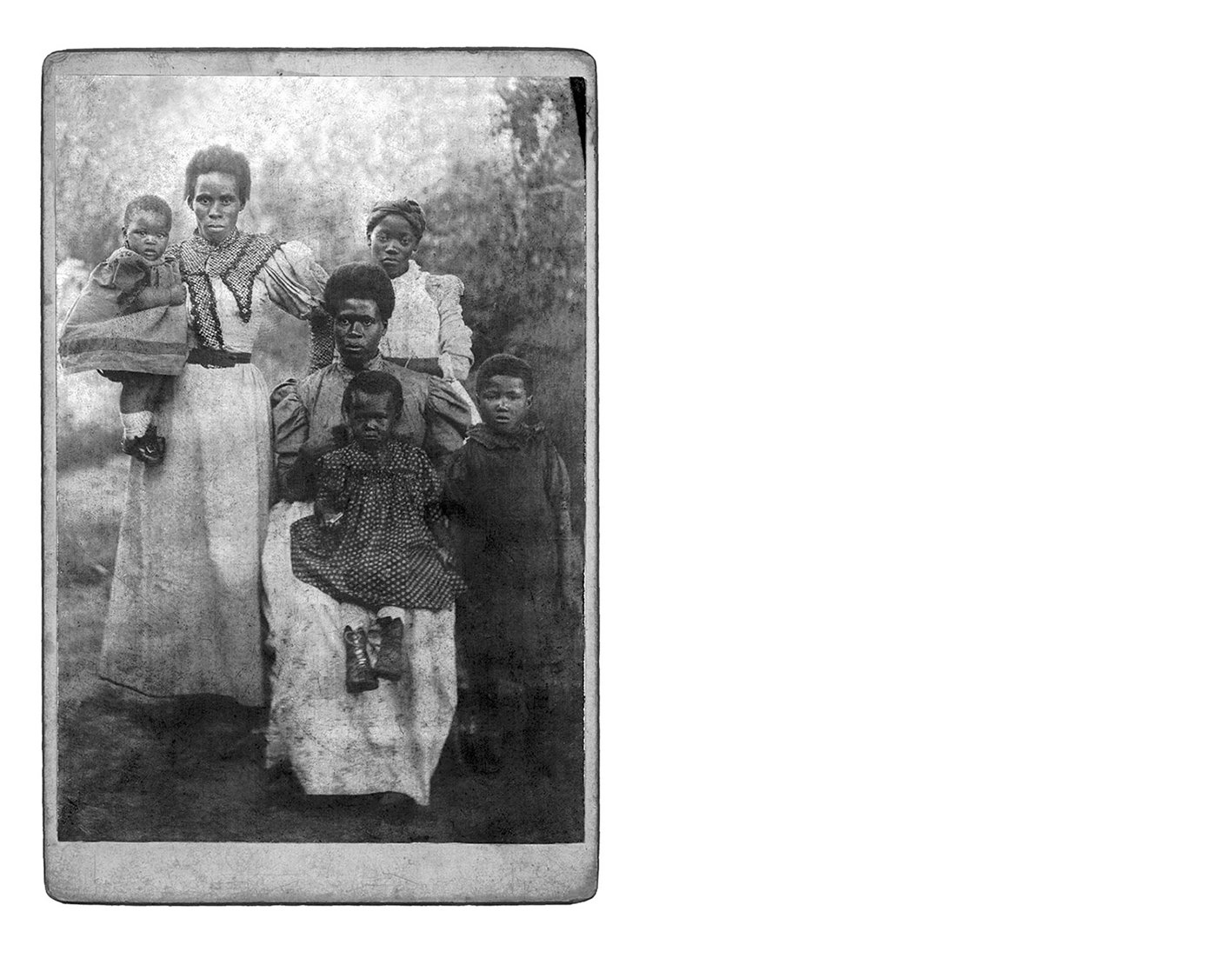

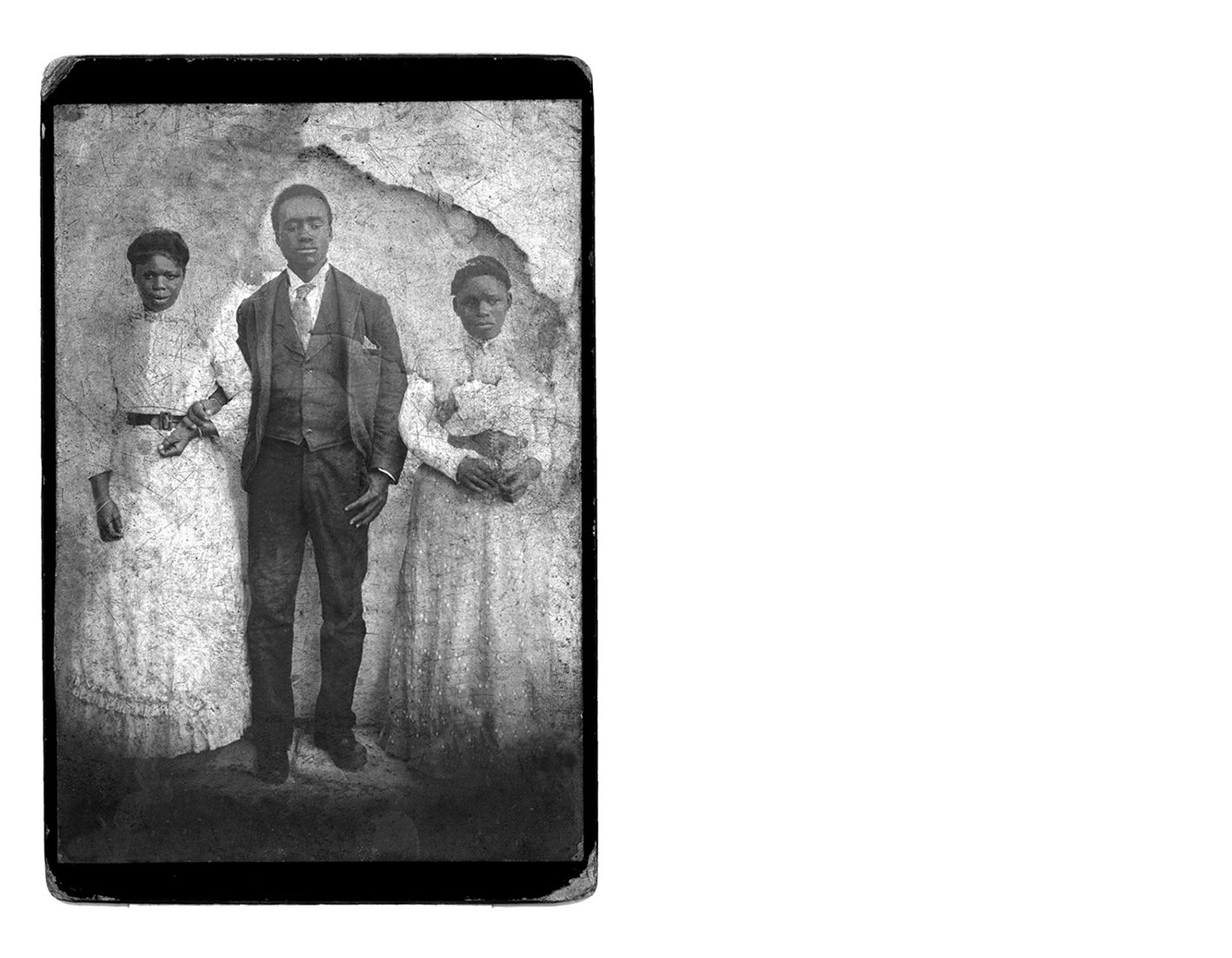

These are images that urban black working- and middle-class families had commissioned, requested, or tacitly sanctioned. They are left behind by dead relatives, where they sometimes hang on obscure parlor walls in the townships. In some families they are coveted as treasures, displacing totems in discursive narratives about identity, lineage, and personality.

And because, to some people, photographs contain the ‘shadow’ (essence) of the subject, they are carefully guarded from the ill will of witches and enemies. In other families they are being destroyed as ‘rubbish’ during spring ‘cleans’ because of interruptions, discontinuities or disaffection with the subject or the narratives encapsulated in the image. Most often they lie hidden to rot through neglect in kists, cupboards, cardboard boxes, and plastic bags.

If the images are not unique, the individuals in them are. Painterly in style, most of them are evocative of artifices of Victorian photography. Some of them may be fiction, a creation of the artist insofar as the setting, the props, the clothing, or the pose are concerned. Nonetheless there is no evidence of coercion. When we look at these images we believe them, for they tell us a little about how these people imagined themselves. We see these images in the terms determined by the subjects themselves, for they have made them their own. They belong and circulate in the domain of the private. That is the position they occupied in the realm of the visual in the nineteenth century. It was never their intention to be hung in galleries as works of art.

The significance of the images lies outside of their frames, i.e. in the realm of the political. They were made in a period when the South African state was being entrenched and policies were being articulated toward a people the government designated ‘Natives.’ It was an era mesmerized by the newly discovered life sciences, such as anthropology, informed by social Darwinism.

A time which spawned all kinds of ‘experts’ (so dearly loved by politicians), who could be conjured up to provide ‘expert knowledge’ on any number of issues including matters ‘race.’ Race thinking was given scientific authority in this period and was used to inform state policy on ‘the Native Question.’

Officially, black people were frequently depicted in the same visual language as the flora and fauna, represented as if in their natural habitat for the collector of natural history. Invariably they were relegated to the lower orders of the species, especially on those occasions when they were depicted as belonging to the ‘great family of man.’

Designated Natives: a discrete group who were considered in a sense citizens, but not altogether citizens. The images so made have formed a part in the schemes of authoritative knowledge on the Natives, serving no small part in the subjection of those populations to imperial power. Images informed by this prevailing ideology have been enshrined in public museums, galleries, libraries, and archives of South Africa. In contrast, the images in this display portray Africans in a very different manner.

Yet all too often these images run the risk of being dismissed or ignored as evidence of pathologies of bourgeois delusions. However, it should be pointed out that, beginning at the turn of the twentieth century and even earlier, there were black people who spurned, questioned, or challenged the government’s racist policies. Many of those integrationists were people who owned property or those who had acquired Christian mission education, and they considered themselves ‘civilized.’ These people, taking their model from colonial officials and settlers, especially the English, lived in manner and dress very similar to those of European immigrants. The images depicted here reflect their sensibilities, aspirations and their self-image.

1 (Ashforth, Adam) Politics of Official Discourse in Twentieth Century South Africa Clarendon Press, Oxford 1990

Refrain

The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950 is drawn from an ongoing research project. The project seeks to create an archive of images that black working- and middle-class families commissioned during the period 1890 to 1950 and the stories about the subjects of the photographs. Those of you with even a cursory knowledge of history will realize the significance of this period. While the world went to war twice during this time, South Africa was busy articulating, entrenching, and legitimating a racist political system that the United Nations later proclaimed, “a crime against humanity!” In keeping with the theme of this analysis, I chose mostly those images that were made in the 1890s to 1900s and a few from the 1910s. A lot of research is still being done to place these images in a more comprehensive context.

The pictures are shown here courtesy of ten families, namely: Dubula of White City Jabavu,

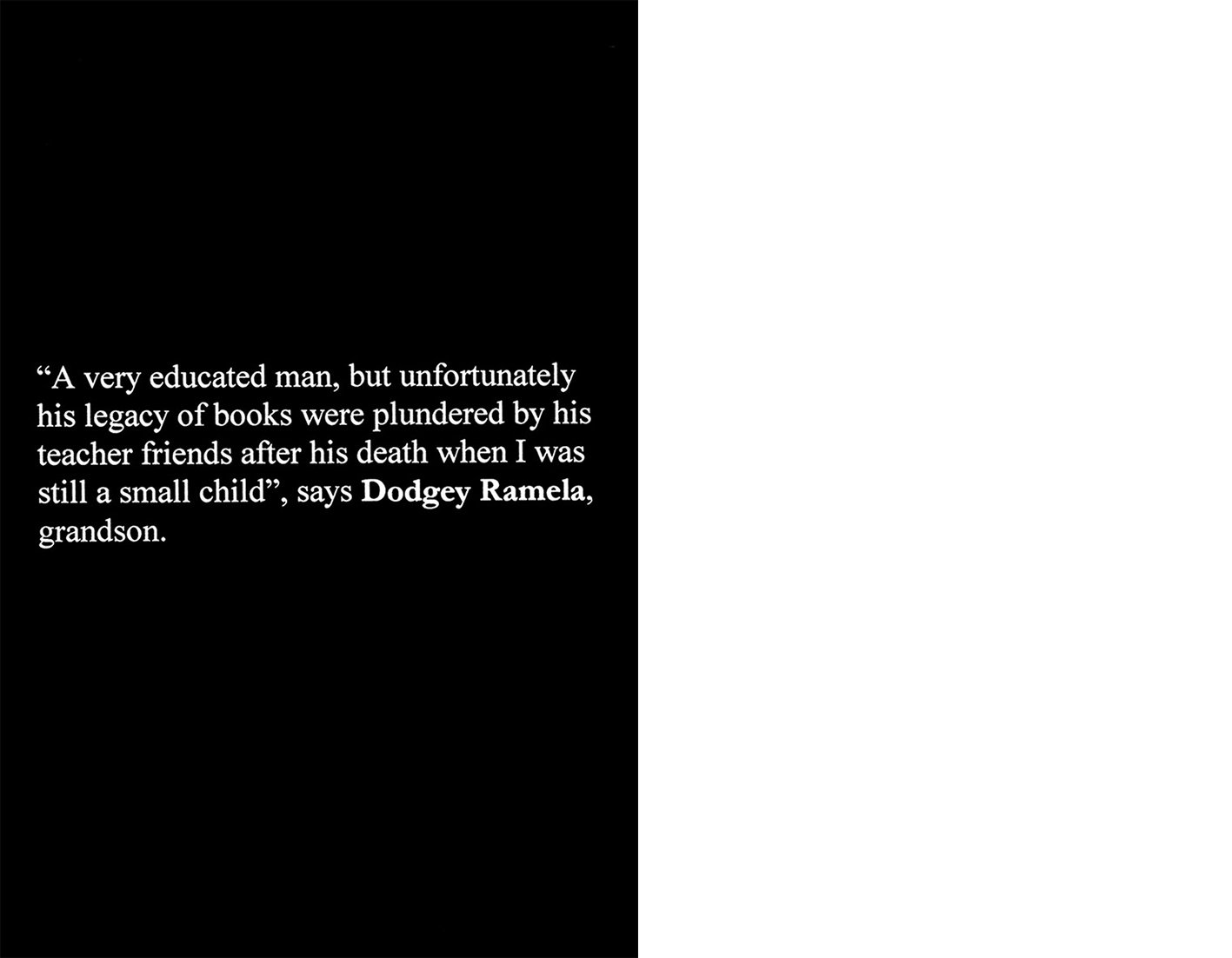

Soweto-Gauteng; Khame of Naledi, Soweto-Gauteng; Mngomezulu of Ledig, Rustenburg- North West Province; Moatshe of Mohlakeng, Randfontein-Gauteng; Modibedi of Mapetla, Soweto-Gauteng; Motsoatsoe of Orlando East, Soweto-Gauteng; Msomi of Mofolo Central, Soweto-Gauteng; Smith of Rocklands, Bloemfontein-Orange Free State; Xorile of Orlando West, Soweto-Gauteng; and Ramela of Orlando East, Soweto-Gauteng.

To create the images presented here, the original photographs were scanned, enhanced, and digitally retouched using Adobe Photoshop software. These digital images were output via an imagesetter and transferred onto 200-lines-per-inch screen negatives, from which contact prints were then produced through a normal photographic printing process.

Santu Mofokeng

Exhibitions: The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890 - 1950

1995

Distorting Mirror / Townships Imagined Worker’s Library, Johannesburg, South Africa

1996

Third International Photographic Biennale Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain

The Black Photo Album / Look at Me Standard Bank National Arts Festival, Grahamstown, South Africa

1997

Trade Routes: History and Geography—2nd Johannesburg Biennale Johannesburg, South Africa

Fin de Siècle à Johannesburg Le Lieu unique, Nantes, France

1998

Black Photo Album / Look At Me Nederlands Foto Instituut, Rotterdam, Netherlands

3es Rencontres de la Photographie Africaine Bamako, Mali

Demokratins Bilder Bildmuseet, Umeå University, Sweden

1999

Journal des Galeries Photo Fnac, Montparnasse, France

2001-02

The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994

Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, Germany; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, USA; MoMA PS1, Long Island City, USA

2002

Survivre à l’apartheid Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, France

Dislocación, Imagen & Identidad. Sudáfrica. Circulo de Bellas Artes, Madrid, Spain; Sala Rekalde, Bilbao, Spain

2004

Santu Mofokeng David Krut Projects, New York, USA

2005

Making Waves—a selection of works from the SABC art collection Johannesburg, South Africa

2009

Imaginar_Historiar XVI Jornadas de Estudio de la Imagen, Madrid, Spain

2010

Santu Mofokeng: Remaining Past Minchar Art Institute, Tel Aviv, Israel

Darkroom: Photography and New Media in South Africa since 1950 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Virginia, USA

Contemporary African Photography from The Walther Collection—Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm, Germany

2011

(RE)CONSTRUÇÕES, Arte Contemporânea da África Do Sul Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2011-12

Chasing Shadows: Santu Mofokeng, Thirty Years of Photographic Essays

Jeu de Paume, Paris, France; Kunsthalle Bern, Bern, Switzerland; Bergen Kunsthall, Bergen, Norway; Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa

2012

Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive, Part I: “Santu Mofokeng and A.M. Duggan-Cronin” The Walther Collection, New York, USA

2012-13

Narrativas domésticas: más allá del álbum familiar Diputación de Huesca, Spain Poetry and Dream Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom

2013

Ai Weiwei, Romuald Karmakar, Santu Mofokeng, Dayanita Singh. German

Pavilion 2013, 55th International Art Exhibition—La Biennale di Venezia Venice, Italy

African Photography from The Walther Collection—Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm, Germany

Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890-1950 FNB Joburg Art Fair, South Africa

2016

The Taipei Biennial Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan

2016-17

South Africa The Art of a Nation British Museum, London, United Kingdom

2017-18

The Shadow Archive: An Investigation into Vernacular Portrait Photography The Walther Collection, Project Space, New York, United States

2018

Apologia della Storia - The Historian’s Craft Fondazione ICA Milano, Milano, Italy

2020

African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other Foto Fest, Houston, United States

2021

Events of the social: Portraiture and Collective Agency African photography from The Walther Collection PHoto España, Madrid, Spain

2022

Aus Südafrika: Santu Mofokeng, William Kentridge, Banele Khoza Kunsthaus Göttingen, Germany

Shifting Dialogues: Photography from The Walther Collection Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, K21, Düsseldorf, Germany

2023

Trace - Formations of Likeness - Photography and Video from the Walther Collection Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany

Selected Publications: The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890 - 1950

Vuka SA, April 1996

Text: Marilyn Martin

Foundation of Education, Science and Technology, Pretoria, 1996

Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Number 4

Editor: Okwui Enwezor

Essay: Santu Mofokeng

Okwui Enwezor, Spring 1996

Trade Routes: History and Geography—2nd Johannesburg Biennale

Editors: Matthew DeBord, Rory Bester

Essay: Octavio Zaya

Greater Johannesburg Metro Council, South Africa / The Prince Claus Fund, The Netherlands, 1997

Reframing the Black Subject: Ideology and Fantasy in Contemporary South African Representation

Text: Okwui Enwezor

Third Text: Third World Perspectives on Contemporary

Art & Culture, 1997

Grand Street 64: Memory

Editor: Jean Stein

Essays: Santu Mofokeng and Okwui Enwezor

Grand Street Press, New York, 1998

Anthology Revue Noire of African & Indian Ocean Photography

Editors: Pascal Martin Saint Léon & N’Goné Fall Essay: Santu Mofokeng

Revue Noire, Paris, 1999

Journal des Galeries photo: mars—avril 1999

Editor: Laura Serani

Text: Santu Mofokeng

Magasins Fnac, Paris, 1999

The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994

Editor: Okwui Enwezor

Essay: Lauri Firstenberg

Prestel Publishing, Munich, 2001

Dislocación, Imagen & Identidad. Sudáfrica

Curator: Daniela Tilkin

La Fábrica, Madrid, 2002

Chimurenga Magazine

Editor: Ntone Edjabe

Chimurenga, Cape Town, 2002

Hans Ulrich Obrist, Interviews, Volume 1

Editor: Thomas Boutoux

Edizioni Charta, Milan, 2003

Making Waves—a selection of works from the SABC art collection

Authors: Koulla Xinisteris and Graham Neame

SABC, Johannesburg, 2005

Messages and Meaning—The MTN Art Collection

Editor: Philippa Hobbs

Essay: Clive Kellner

David Krut Publishing, Johannesburg, 2006

Photography and Africa

Author: Erin Haney

Reaktion Books Ltd, London, 2010

Contemporary African Photography from The Walther Collection—Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity

Editor: Okwui Enwezor

Essay: Santu Mofokeng

The Walther Collection / Steidl, Germany, 2010

(RE)CONSTRUÇÕES, Arte Contemporânea da África Do Sul

Editor: Daniella Géo

Texts: Daniella Géo, David Koloane, Guilherme Bueno

Niterói Museum of Contemporary Art, Rio de Janeiro, 2011

Chasing Shadows: Santu Mofokeng,

Thirty Years of Photographic Essays

Editor: Corinne Diserens

Essays: Adam Ashforth, Okwui Enwezor, Patricia Hayes, Sarat Maharaj, Ivan Vladislavic and Sabine Vogel

Prestel Verlag, Munich—London—New York, 2011

EXIT 45: NUEVO DOCUMENTALISMO

Editor: Carolina Garcia

Essay: Santu Mofokeng

Cataclismo, Madrid, 2012

UNFIXED: Photography and Postcolonial Perspectives in Contemporary Art

Editors: Sara Blokland and Asmara Pelupessy

Essay: Kobena Mercer

Jap Sam Books, Heijningen, UNFIXED Projects, Amsterdam, 2012

Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive, Part I: “Santu Mofokeng and

A.M. Duggan-Cronin”

Editor: Tamar Garb

Essay: Kerryn Greenberg

The Walther Collection, New York, September 2012

African Photography from The Walther Collection— Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive

Editor: Tamar Garb

Essays: Tamar Garb, Jennifer Bajorek

The Walther Collection / Steidl, Göttingen, 2013

Narrativas domésticas: más allá del álbum familiar

Author: Nuria Enguita Mayo

Diputación de Huesca, Spain, 2013

Ai Weiwei, Romuald Karmakar, Santu Mofokeng, Dayanita Singh. German Pavilion 2013

Editor: Susanne Gaensheimer

Essays: Achille Mbembe, Santu Mofokeng

Die Gestalten Verlag, Berlin, 2013