Townships

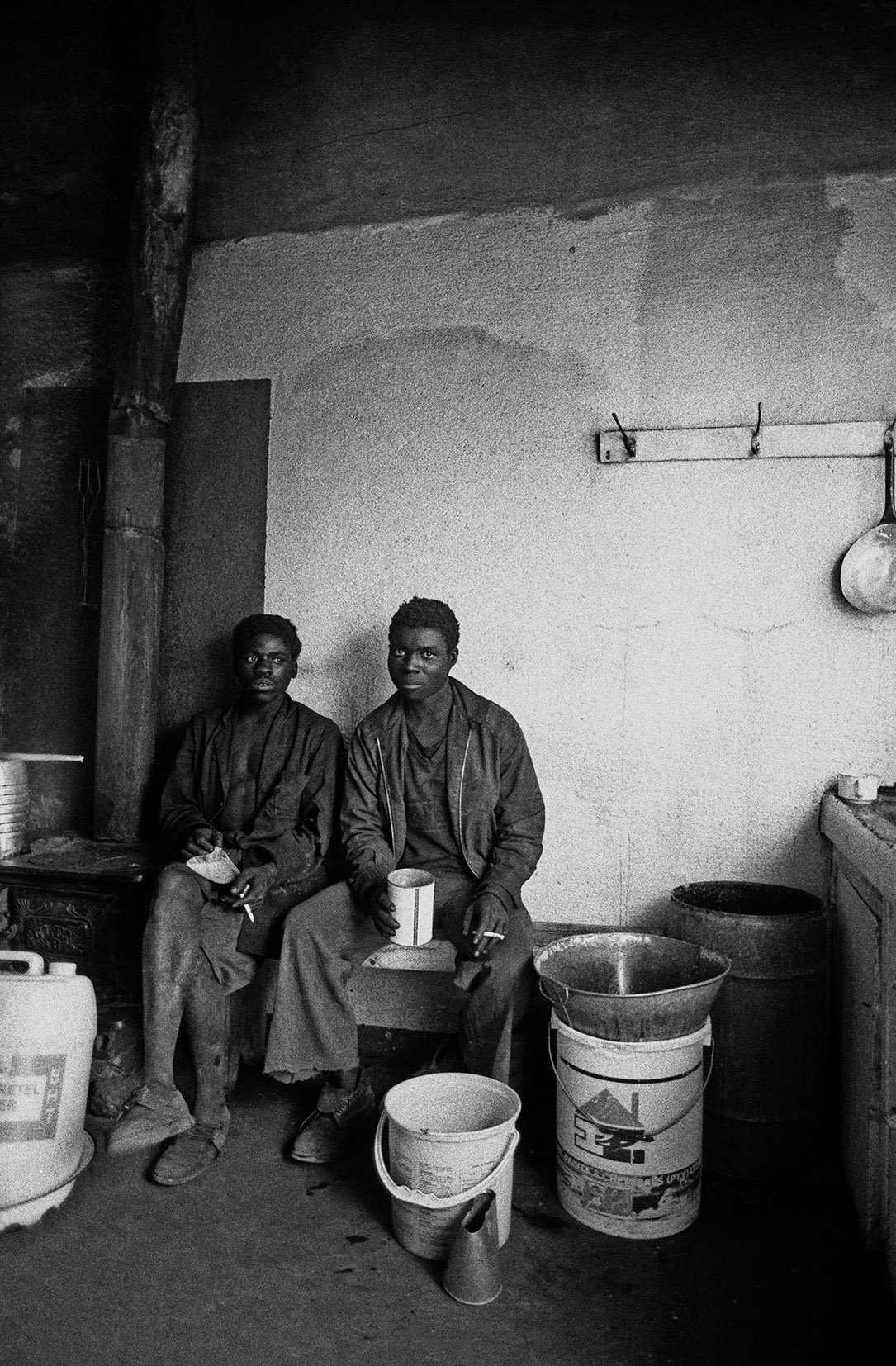

They suffer abuse mostly quietly, except maybe give a dull wooden thud or a metallic twang when struck. They provide illumination. They are viewed with suspicion by some, they are mostly ignored by most. They are taken for granted. They are there to lean on or to piss on. I aver, lamppost is the metaphore of our experience.

* * * * *

I was born to a migrant worker (resident alien) and a domestic worker, Johannes and Martha Mofokeng, respectively, 45 years ago. The address given as home was my mother´s place of employment in Observatory. I was my father´s 10th child and my mother´s sixth. My father had been married twice before he met my mother. He had little more than three years to live when I was born, in which time he managed to squeeze in two more children.

My formative years were split between Newclare, Sophiatown and Orlando East. In Orlando East there was my aunt, grandma, mom and dad and eleven children - including my aunt´s four - all of us living in a three roomed mansion, which began to shrink as I grew up. One happy family sharing.

Then came 1960.

My father died in 1960. I still don´t know how old he was. Angie, our last-born, died in her seventh month the same year, and grandma also. I contracted TB, as did my siblings; my younger brother and my older sister.

The TB was godsend. Because of it we qualified for welfare relief. Every week we collected powdered milk and the dreaded sorghum meal - from which we made `mosoko´pap - and peanut butter, of which there was never enough.

Mom was unemployed when dad died. My father would never allow her to work, although she was more educated than him. My aunt, being older than my mother, inherited the house, started to behave like the queen bee. She allotted one room to mom and us six children, and from then on we enjoyed separate amenities.

Mom had to forage, but us kids never got wind of this. She´d be up by four in the morning and foot it from home to the markets in Bree Street, about ten kilometres away, to pick up soiled fruit, greens and some overripe offerings from the vendors. She would come home late in the afternoon like a regularly employed person. At other times she would work temporarily for the whole month as a domestic only to discover the place deserted on pay day.

I don´t know which came first, the smokes or the bottle. Nevertheless, mom was never the same again. She began to spend more and more of her time at Dorah´s shebeen in Diepkloof. Sometimes we would not see her for days. I started to wet the bed, my sister and younger brother as well.

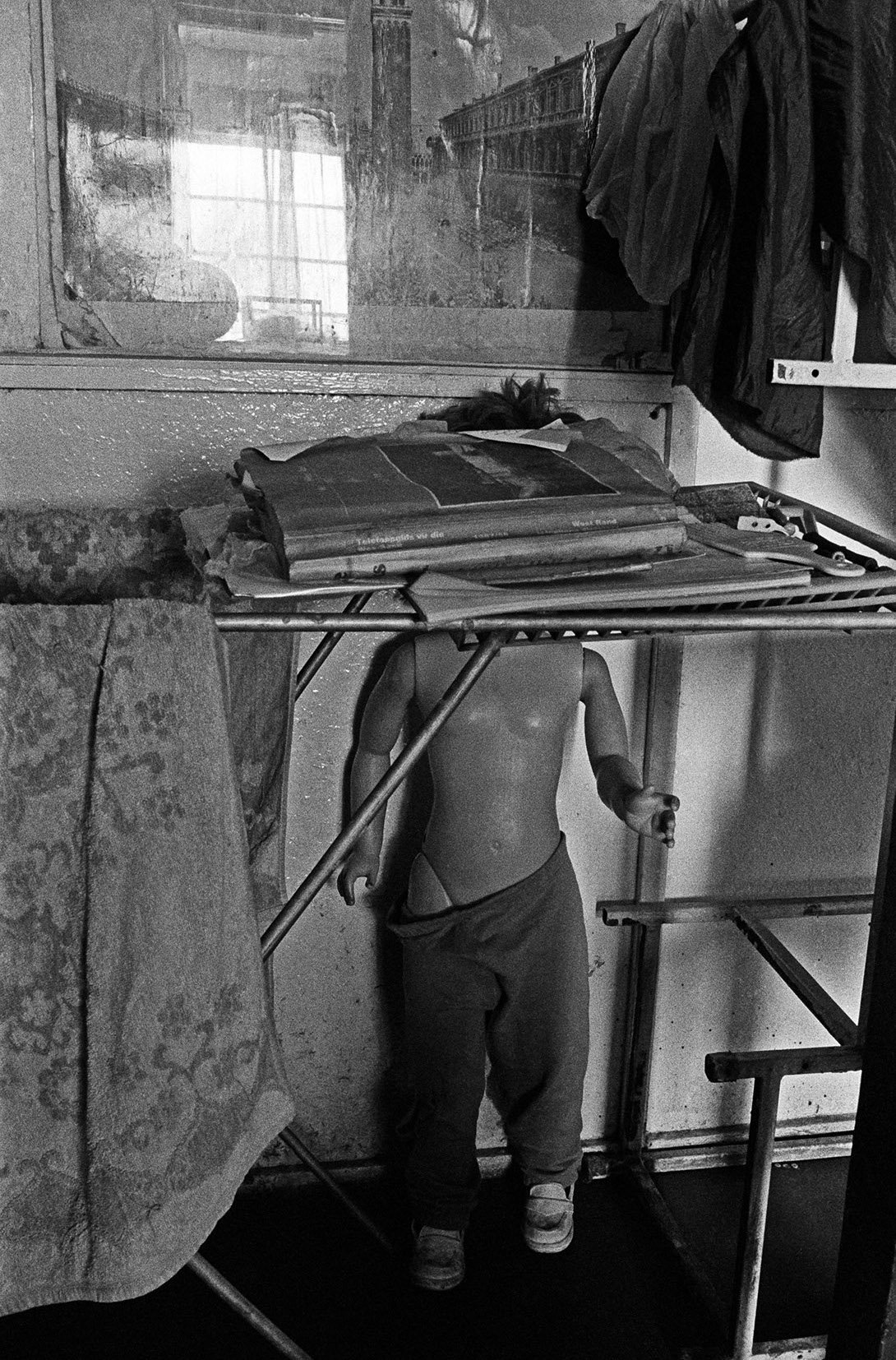

Mother then found steady employment as a presser at the Tiger Clothing Factory which became Dugson´s later. The work finally left her right arm slightly numb - paralysed and weak. She had meanwhile acquired a pedal sewing machine with which she turned out our clothes, blankets, and virtually everything else made of cloth.

But, home made pants, shorts and flannel vests were not exactly fashionable at school in my day. And schoolkids can be can be ruthless. I was always in some scrap or another. I was always late with my school fees, never owned a new text book except the ones that were occasionally donated, and I never went on school trips, whether recreational or or educational. It is a miracle that I did well.

Mother married again in 1968 - ostensibly so that she could apply for a house she could call her own. That was law. The man came to live with us in the single room partitioned off by a wardrobe. It was too much for us and for my aunt. She was threatened because she was single. She booted us out in 1973.

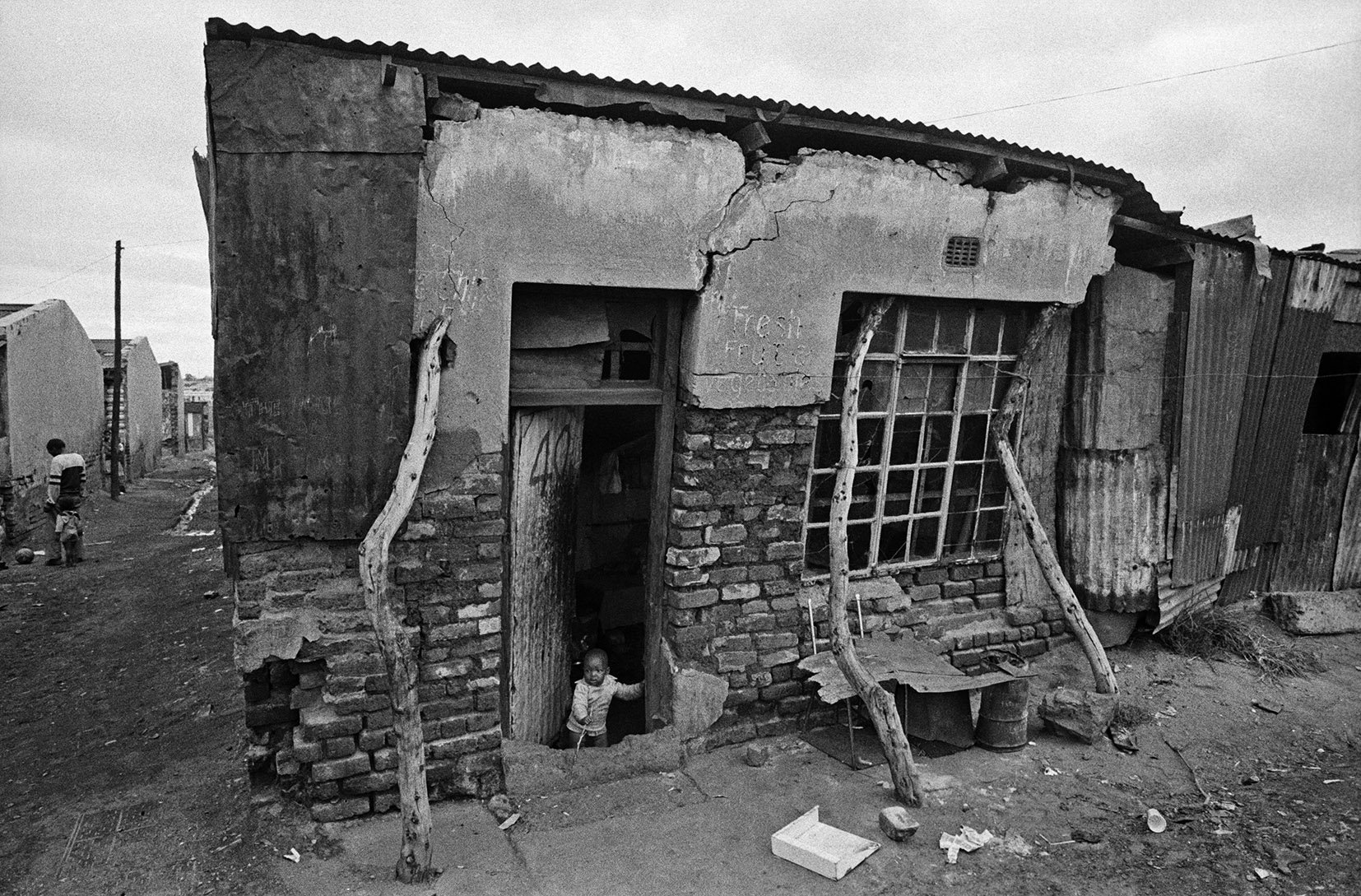

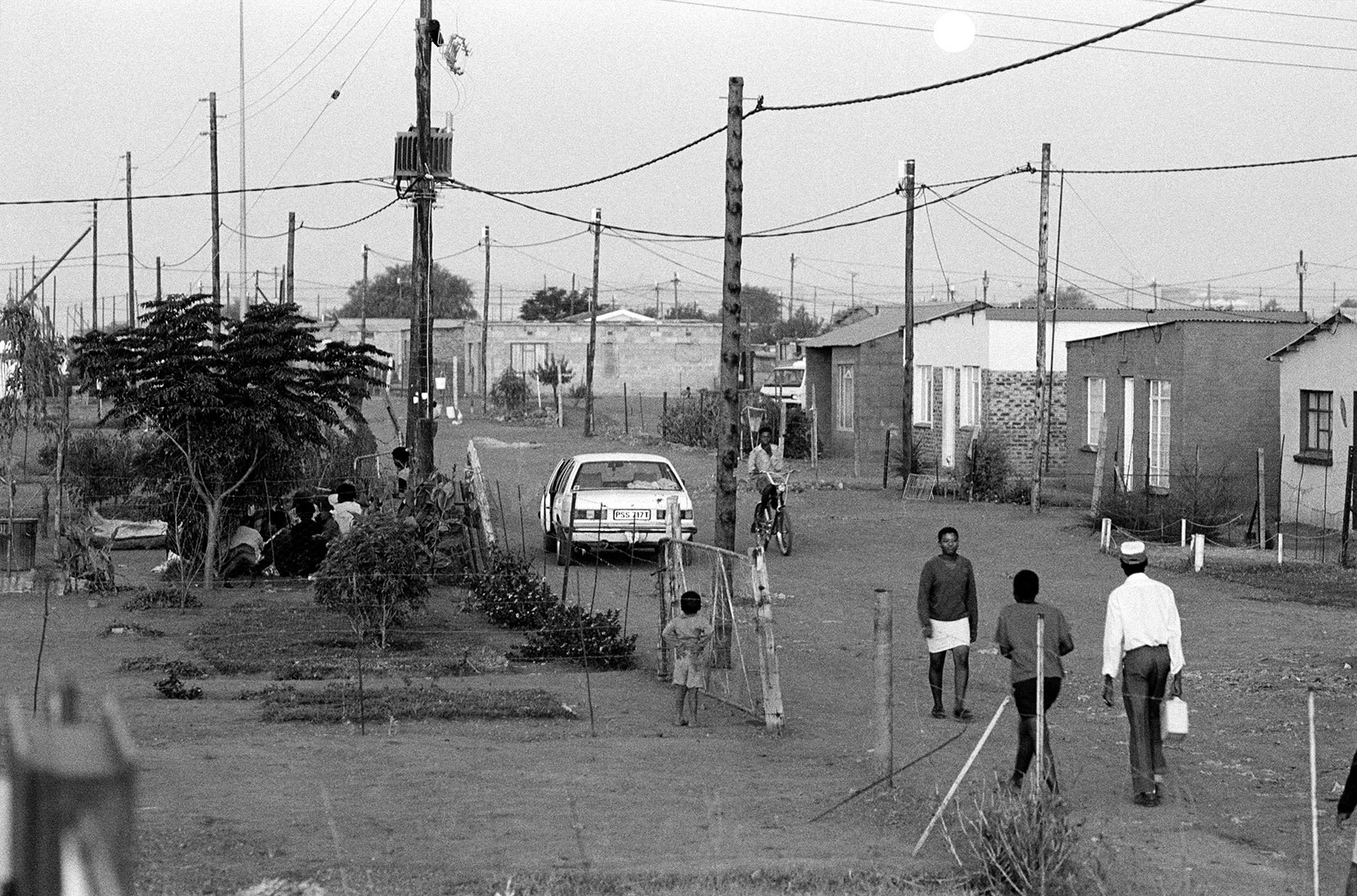

It was in 1973 that we came to be in White City Jabavu and a new beginning. Home at least to ten people. A two-roomed concrete block. Home at last.

My younger brother was fighting to be normal again. He had a limp in his left foot and voices in his head from a shooting incidence in Orlando in 1974. He took up Karate to occupy himself. I would come home for lunch - to sleep as there was never any food - and thereafter run back to school. I would find the house reeking of sweat, him busy with his excercises

Oh, Benjamin Peter Michael Moruti! So named because he was born in the eleventh or twelveth month after my mother coneived him. The birth came about with the help of a priest (moruti) whose name was Peter, and Michael after my uncle. Bennie, as we called my younger brother, was special. His birth was a miracle. He was not supposed to have been born, as my mother´s womb was “locked“ by muti. He came out into the world smeared by ash which the priest had used to wash my mother with, apparently. He died in 1981, suicide is suspected. And this happened despite all the prognosis to the contrary, from seers, traditional healers, sangomas who said I was supposed to die instead. His death broke my mother´s heart, she died in October the same year, of hypertension.

* * * * *

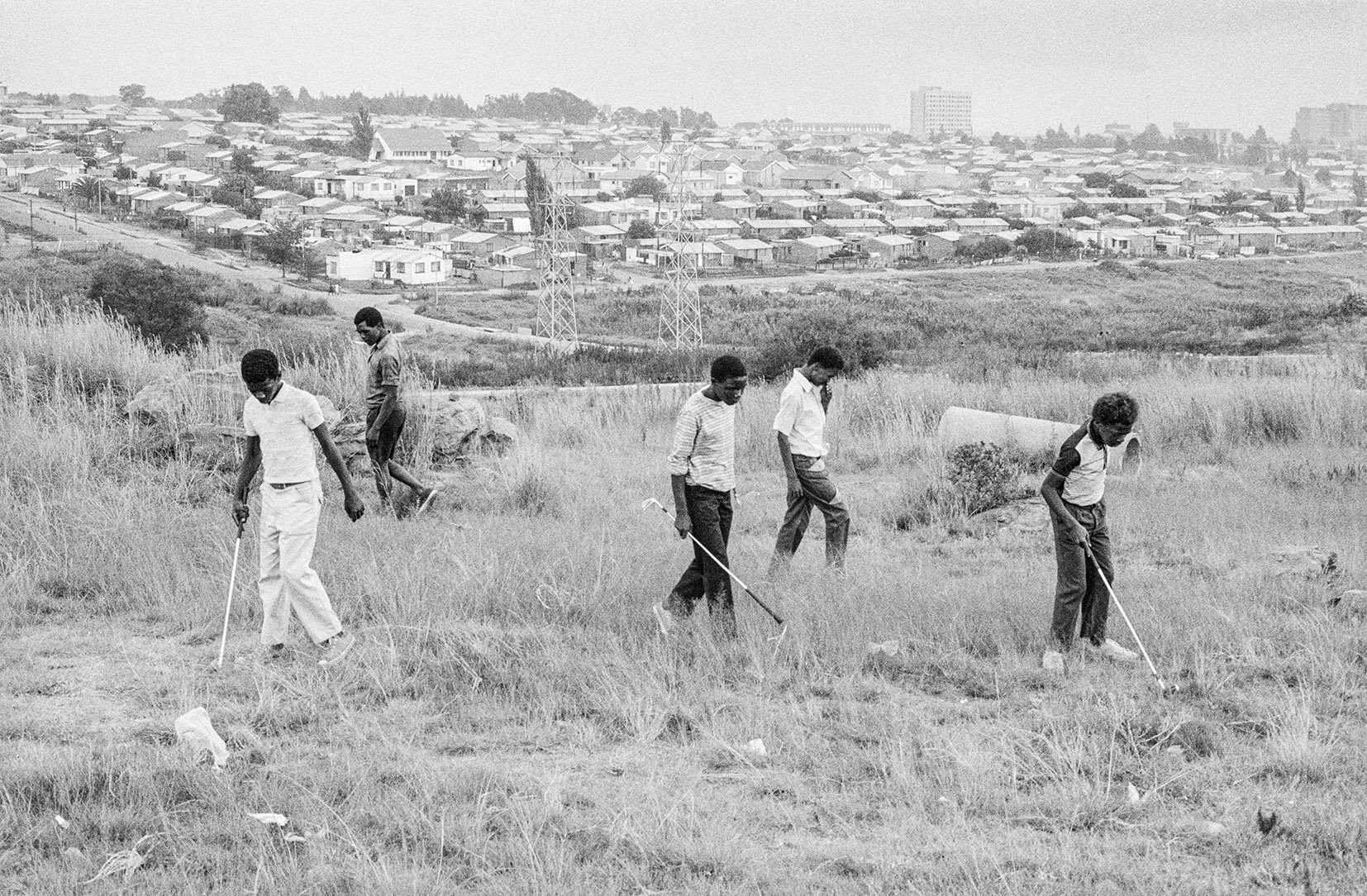

Orlando East, 1960s

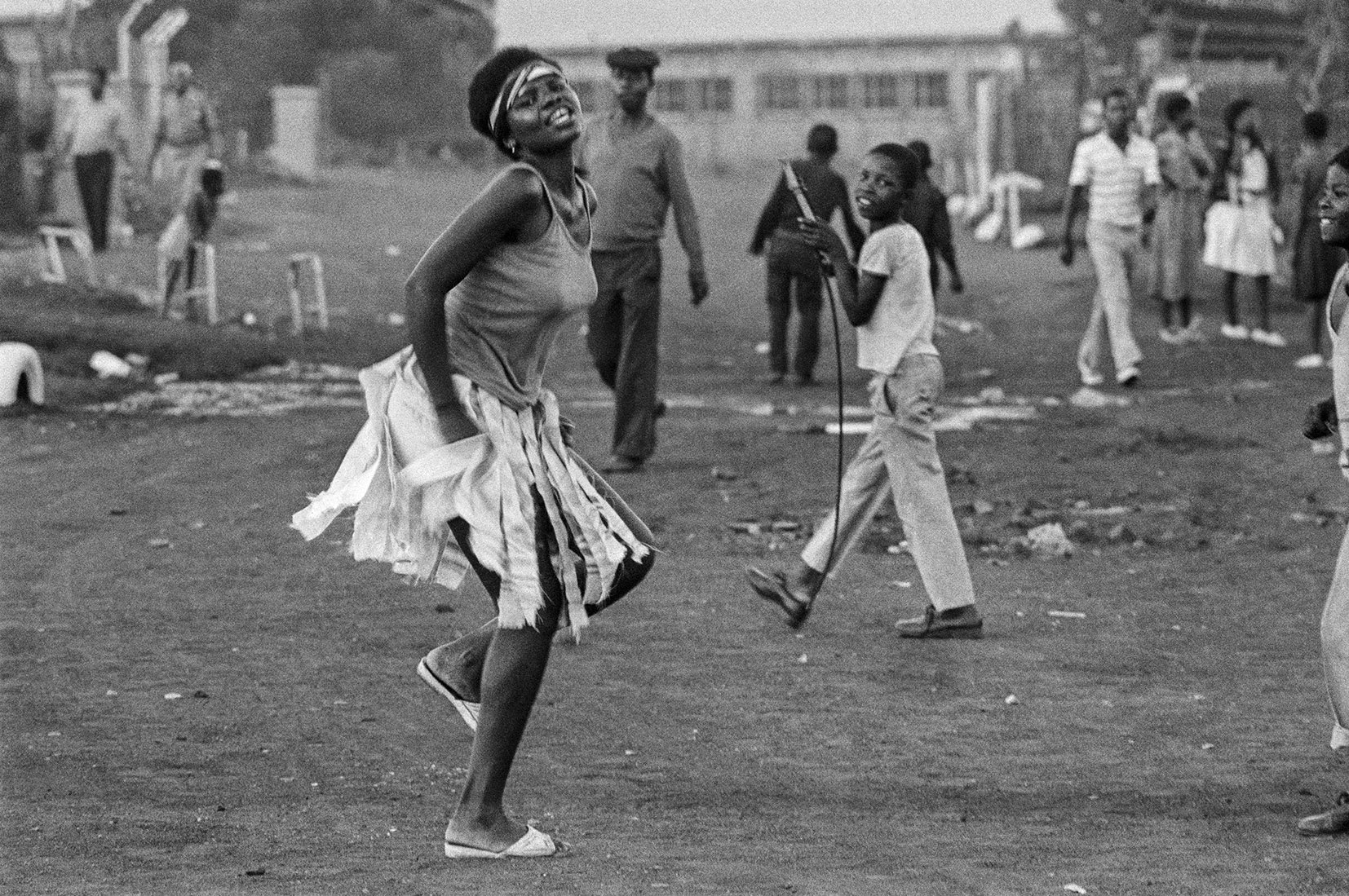

A lamppost stands directly in front of our house in the Orlando East of my youth. Every evening I would escape the gloom of our family room, which is dimly lit by a candle and the blue and ember flames of the brazier fire, in which hangs the smog, the pungent smell of carbon monoxide, boiling cabbage or offal - to avoid the gaze of my elders, petty errands and dull adult conversation; in order to pursue the company and mischief of other children playing hide and seek by the street light. "Black maipatile" we called this game. Screaming "mee mmee!", we would disappear into gardens of mielies, climb peach or apricot trees and hide behind the hedges until discovered.

This frolic provided us with the opportunity to steal peaches or apricots. Sometimes we would try to fuck the girls who followed us to our place of hiding, to the refrain, "I am going to tell." I was about six or seven . The games invariably ended before a quarter of eight, when we would run back to our different homes to huddle near um'sakazo, a Zulu and Sotho redifusion FM broadcast, to listen to a 15 minute installment of "Raborikgwana" - a drama serial on the radio, after which we had our supper and bed. The SABC regulated our playing time more than any parent could.

* * * * *

Orlando East, 1960s

There is Phumelangaphandle, which name we gave him and it translates literally thus, „get-out of- the-house. He was my aunt´s lover. And Mdungazi, the Shangaan with yellow teeth, is another character. He had a gammy leg and we used to mock him whenever he laughed because of his teeth. Our neighbour Sephara, a Royal reader by his own account, liked to tease my step-father, ex-body duilder and pianist, by calling him a „wolf“. Mothobi, a war veteran who saw battle in Normandy and North Africa, who entertained us with his military drills whenever he got drunk and went into a trance.

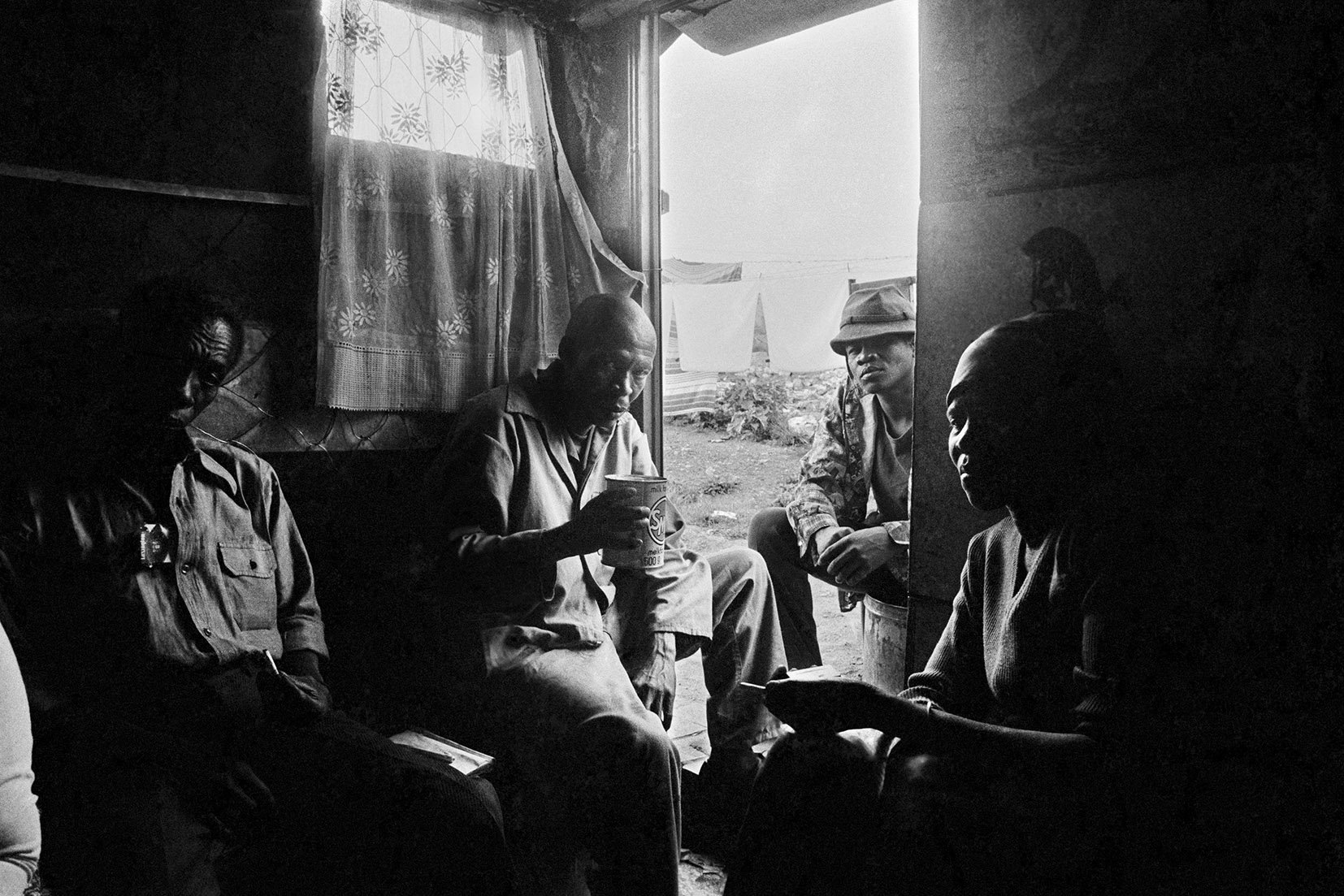

Commuter buses disgorged these and many other workers on the outskirts of the township every night. The workers would then negotiate a grassveld, approach the street lamps on the periphery of the township,

dispersing, sometimes in groups in the direction of their homes, some to the Beerhalls, others to our home because my mother was a brewer. There was this lone "tsotsi", a thug, who preyed on stragglers among the workers. He would come up behind, lob a dustbin over the head of the unsuspecting victim. Stunned, blinded, hands pinned to their side by the bin, the poor victim's pockets would then be emptied. He was a phantom; nobody knew who he was until one of his victims, bin over his head, hands pinned to his sides, bolted. Caught completely by surprise, the thug gave chase - spontaneous reaction, surely. On reaching the perimeter of the township, the thug was identified. Needless to say the thug's career was finished, Amadod´omzi (the civil guards) made sure of that.

* * * * *

In the day, the lamppost stands mostly ignored, taking the hot with the cold, the wind and the wet in silence. We children, armed with slingshots, hunting sparrows and pigeons, would often use the street lamp for target practice. Popping bulbs of the street lights was accidental. It became a pastime for some.

The municipal blackjacks (South Africa´s black Bobbies on the beat) had their hands full trying to capture these miscreants. I still maintain that the Johannesburg City Council relinquished the administration of the township in disgust,(1969 or 1972???) because they were unable to cope with the job of replacing broken bulbs.

* * * * *

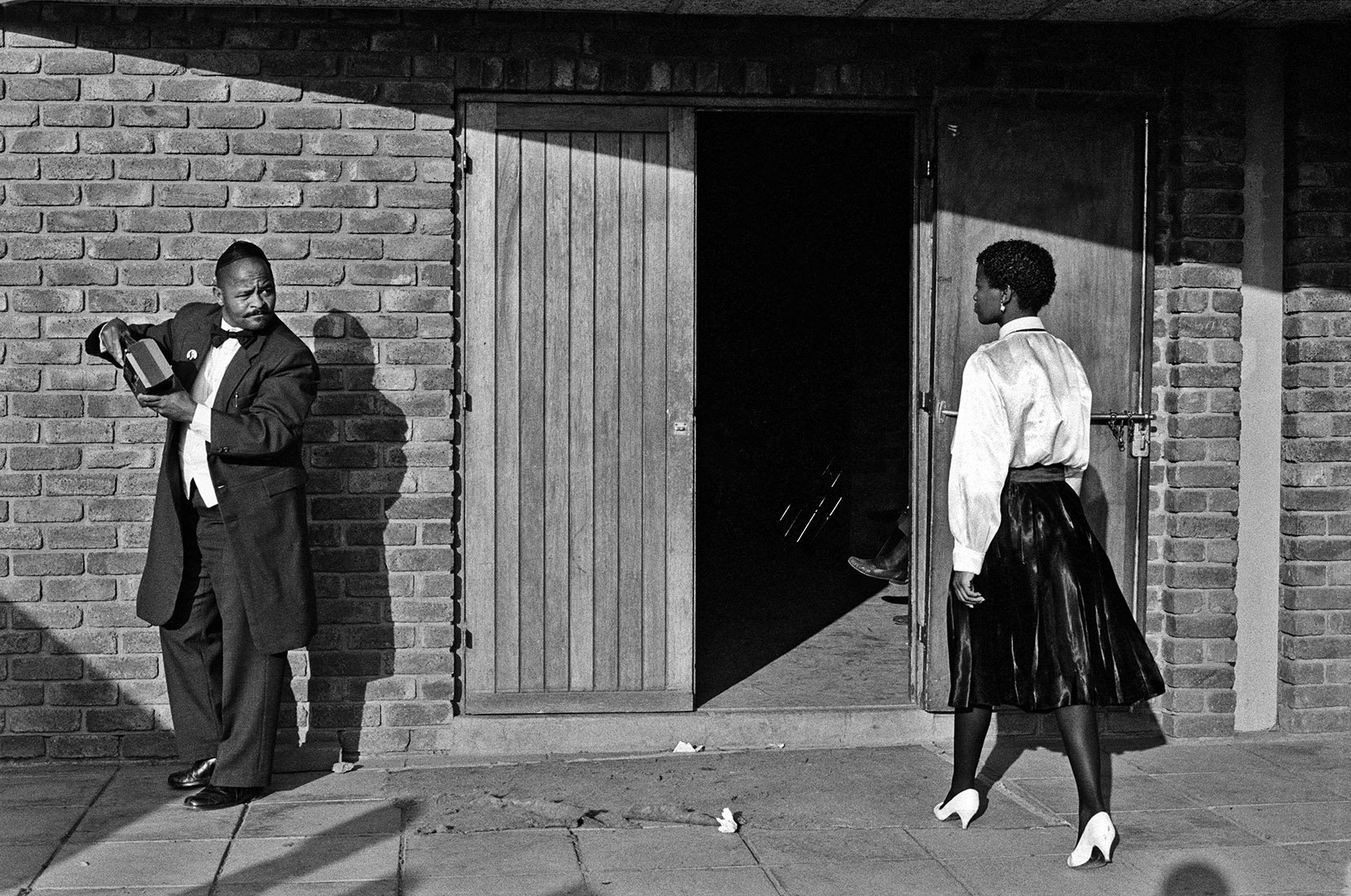

White City, 1970s

The current perception among the youth in the township is that the new apolo lamps are instruments of surveillance, their purpose being to monitor the youth´s clandestine political activities. Therefore, they are to be regarded with suspicion. Lampposts!

* * * * *

Johannesburg, 1981

In 1981 I was 25 years old, in-experienced, literally plucked from the streets. and only Johnny Maloisane to vouch for me as a good honest black man.

"Hy is vertroubaar, baas. Hy is a goeie man, baas," he told Jan Hamman, the chief photographer. To Jan, who is basically a decent man, one of Souht Africa´s finest photographers, I was a puzzle. I didn´t belong in the darkroom because of my qualifications. He reassured me that my job was not dirty.

I was given a white dust coat. I took the job, the abuses and the insults. Thus my career in photography began. I spent the first day at work playing with metal spirals and discarded films learning to load.

My mother had doubts about my career change. She died suddenly the following week, of hypertension.

I learned a lot in that newspaper darkroom. Mainly that black skin and blood make beautiful contrast. This from a conversation overhead in the office: "Come check at this. Isn't this beautiful?" he enthused. The subject of this outburst of glee is a transparency. The tranny depicts a corpse, an ANC cadre bleeding in death, lying on asphalt near a curb. A casualty in what is now known as the Silverton Siege (Date?).

"I don't get it. I see nothing beautiful in this. This is ghoulish, man."

"You know fuck all, China. This is a masterpiece. There's nothing as beautiful as a black skin and blood. It makes beautiful contrast. There's nothing like it, China."

* * * * *

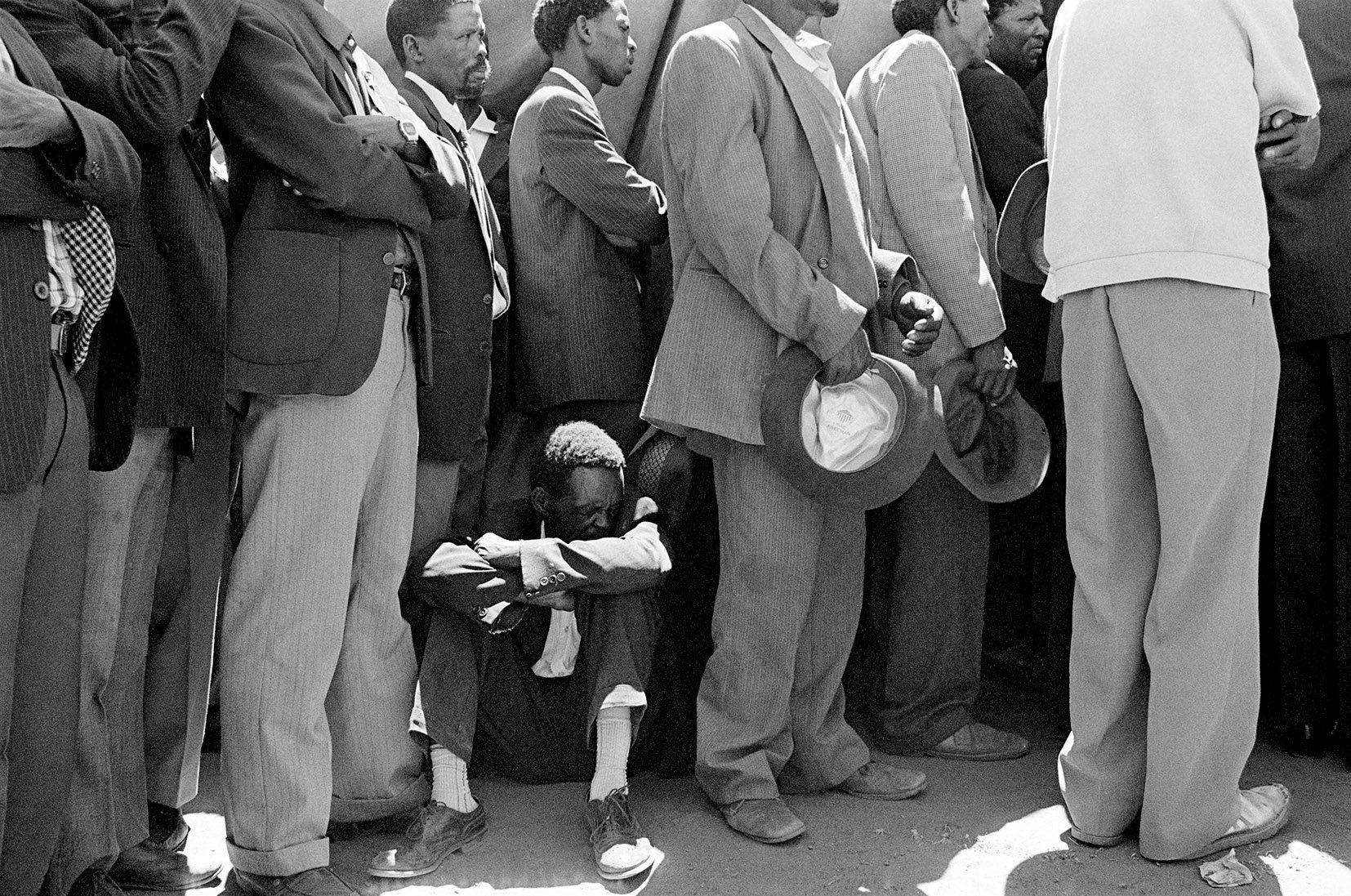

Orlando East 1973

We are sitting at the municipal offices in Orlando East. My mother, stepfather and us six children had been bundled early that morning and marched to the municipal offices for living illegally in a house I had come to call home. We were summarily charged and fined. What I seem to recall from this episode is the enthusiasm with which the municipal blackjacks carried out their duties, taking their cue from the superintendent to escort us to the Orlando East police station. Mom then requested permission to speak to her employer. This was granted. she spoke to her employer, a white woman - I vaguely recall her name - Esther. She in turn intervened on our behalf with the Superintendent. They spoke on the phone at length, in which time I began to ponder our fate. I was doing junior high at the time.

The Superintendent made another phone call. He had a reddish pink complexion, an ugly man indeed.

Gentian violet around his ears did not help matters. I could not read his expression. Inscrutable and cold are the words that come to mind. I don't know for sure. He was fumbling with documents on his desk. He asked to see my mom's and step father's reference books. Marriage certificates. Scribbled something. Stamped some document. He enquired after our names, births, our "fathers", places of birth, etc. He finally waived the fine. A house was allocated to us in White city Jabavu. Thank God! Although we were born in Johannesburg, he gave us 10:1(d) qualifications - which means conditional residency permit, a status reserved for migrants.

We were later to learn the reason why our new home had been vacant - there had been a murder in the house. A son had killed his own father in that house.

* * * * *

White City Jabavu 1990s

Vusi comes into the kitchen where I am sitting talking to my sister. He sits down. He doesn't say a word. My sister nudges him and asks: "Vusi, do you know who this is?" pointing at me.

Vusi shakes his head, No.

I ask my sister, What's with him?

Vusi's family were our neighbour when we were living at 1510c. I think he was eight or ten when he was knocked down by a car. Something about his brain qualified him for disability pension.

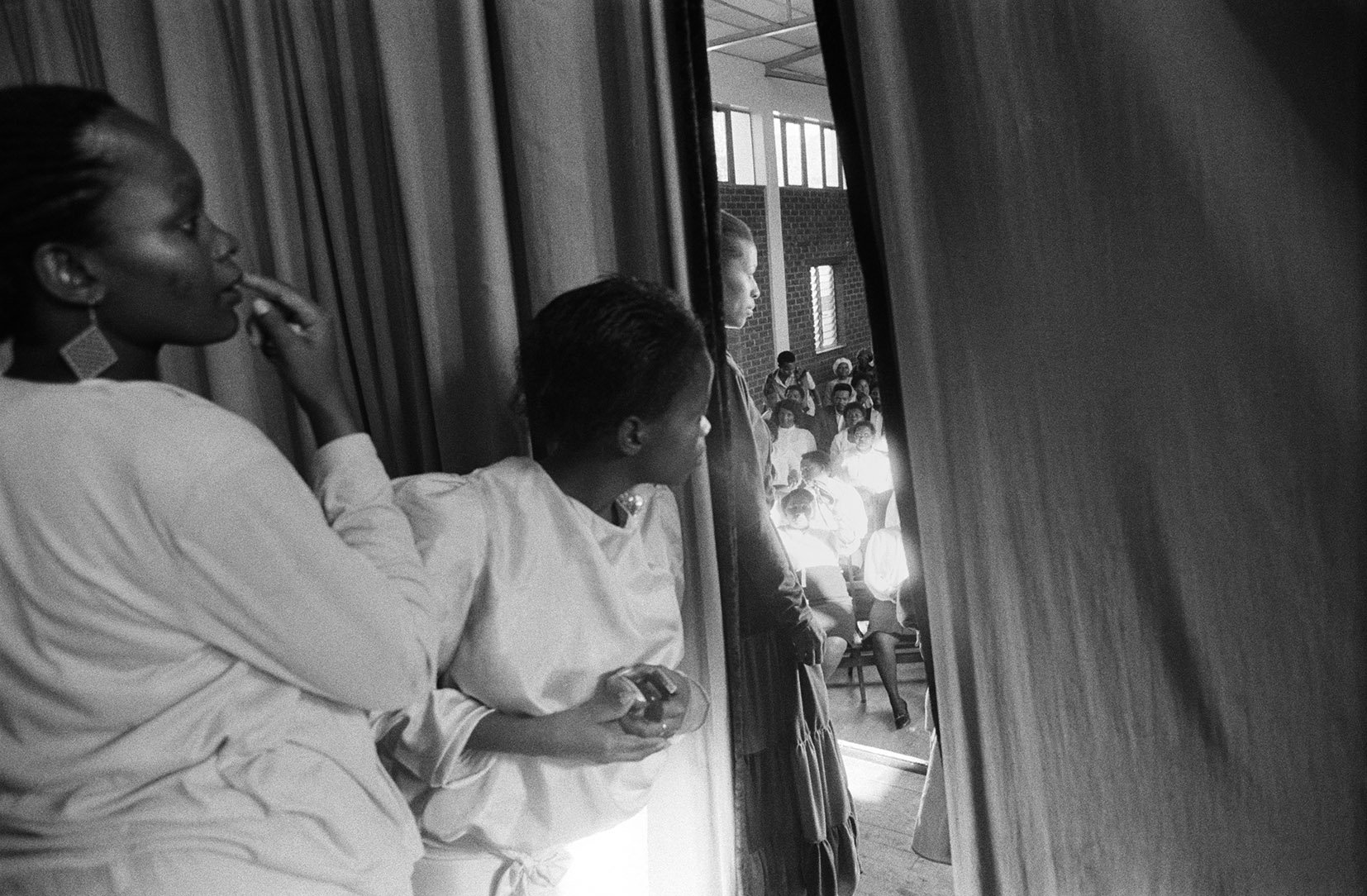

My concern stems from the fact that in '85 when the state of emergency was declared in South Africa Vusi helped me in my work. The youths were mobilized at the time and they were running gunshot in the townships. Meetings were banned. It was forbidden to take photographs of unrest.

Mobilization sessions took place mostly at night vigils, funerals and secret locations. I wanted to document these going-ons at night vigils. I was ignorant of the fact that youths who were on the run from police usually made their appearances at these night vigils, and that the police might have special interest in my photos if published or if I was arrested. Vusi was a comrade - Soweto speak - at the time. I asked him to accompany me to a funeral in Emndeni. He was going to introduce me to his friends. A comrade was being buried there.

We arrived at the wake around 11:00 pm. I explained my presence to a coterie of youths who seemed to be in control of the proceedings. I told them who I was, showed them my Afrapix card and my new reference book. I had been to collect my reference book earlier in the day. I was proud of it because my qualifications had been changed from 10:1(d) resident alien to 10:1(a), which meant I was a bona fide resident of Johannesburg.

To my surprise, the new reference book was proof to the comrades that I was an informer, a spy in their midst! I was interrogated in the kitchen. Found guilty, condemned. In the background I could hear freedom chants. The night vigil was in progress.

Vusi was also in trouble. Those few comrades whom he knew, who could vouch for his credibility, looked another way.

Some violently dissociated themselves from him, lest they be tainted - seeing that his allegiance was being questioned.

They were trying to force him to betray me. He refused. He was made to drink a bucketful of dirty water saturated with detergent so he could tell the truth. He still would not betray me to save himself.

My turn to drink the detergent water came and I refused. My cameras had been confiscated by then. A photo session with my own camera equipment was in progress.

Youths were sent out to collect tires from a "peace" park nearby. There was a commotion when they tried to force me out of the kitchen.

My mouth was dry. Everything began to seem unreal. My voice did not feel like my own. Surely this is not me! The light seemed to change.

I remembered a particular moment as a child coming home from school. There was an eclipse of the sun. The grass was yellow of winter, the ground was unreal. The day wasn't as bright as it normally is. I have tried to capture this feeling on black and white film, with little success. The nearest I could achieve is an overexposed negative of an albino, not necessarily in sharp focus, printed on contrasty paper to tease out as much detail as possible, developed on exhausted developer or warm paper. Try your luck in the darkroom.

Imagine the headlines: "SANTU MOFOKENG, NECKLACED!". I am not an informer, or am I?

A voice intervenes: "We are in mourning here. Please stop it. You can deal with him in the morning, however you please. Not here." This woman looks at me and beckons me to follow her to the bedroom, where the bereaved family is gathered for the vigil. Vusi was also rescued in this way.

My confusion comes from the fact that I had not seen Vusi in a long time. As I learned now, Vusi had just been discharged from a hospital after spending weeks being unconscious. He had been involved in a fight. He stopped a brick with his head, knocked out cold. He suffered loss of memory. His speech phlegmatic at best, is now slower, deliberate and inaudible.

* * * * *

Darragh House 1987

Kano is everything I am not. Confident, humorous and energetic. He gets his own way with me. He is likeable. He writes me letters like this one:

Dear Dad,

I have been grounded for I don't know. But the good news is I am trying to be a good boy at home. From your loving son, Kano

On the opposite side of the letter is a picture he drew of Noah's Ark, with lightening, clouds and floods. He thinks I am invincible! He is eight.

Kano was spending a weekend with me, after my wife and I separated. I took him to work with me, that Saturday morning. I leave him in the newsroom, where colleagues could keep watch while I steal a moment to go upstairs to union offices to make photographs of the famous NUM 1987 mineworkers strike.

Half an hour later, I come back to the newsroom. Kano is not there. I enquire in the office about his whereabouts, I get negative responses. This is a joke, right? I do not panic. He is probably gone to the store with one of my colleagues. An hour goes by. I begin to enquire seriously. Negative. I look in all the offices in the building. There are only two floors. I draw a blank.

I go back and talk to union members and officials: Yes, Kano was seen in the company of one of their members. They don't know where that person lives. He is only known as Rasta, from the East Rand. He is a migrant worker, from Transkei. He is presently unemployed.

Who is this man? Abduction? Should I call the Police? Out of the question. I ask my friends in the union movement to help me scour the vicinity of Johannesburg station. Night falls. I sleep on the benches of the union.

My problem is only one of many the union is dealing with - police beating striking mineworkers, factions fights in mine compounds between scabs and strikers.

I need transport to Tsakani. Where? To do what? To look for whom? Rasta. Who is Rasta?

Witchcraft? The threat of it. Could my son have been abducted for the reasons of muti? Santu, don't loose your head. Tomorrow, Rasta is attending the union meeting. He will bring the child with him. He is probably trying to find me or to return the child to its rightful parents.

The morning comes. Nothing doing. I phone Eric Miller, a colleague at Afrapix. He offers to drive me to Tsakani where a union branch official may know where Rasta lives. We drive to Tsakani, no luck. We come back to the union offices. We are directed to a hostel in the East Rand. A union member who knows the hostel and Rasta's friends accompany us. Chris, a union organizer, is with us. We drive to the hostel. We are directed to a house where Rasta lives.

On arriving at the house, we are told yes, he came home yesterday with his son, claiming the mother dumped the child on him. He has been boasting about the child to everyone. They tell us, he washed the child's clothes and hung them overnight to dry.

We look for Rasta at his haunts. It is midday, no luck. Around early evening, Sunday, I begin to despair. Having done everything we could, Eric decides we should hand matters over to the police. I insist we take one last look at Rasta's place; we draw a blank.

As we are about to leave Tsakani, on the main road which will finally take us to Johannesburg my heart gets heavier by the minute. In my mind I am imagining Shakespeare's three witches in Macbeth - our set book in Matric:

First witch: We needed his tongue

Second witch: We needed his genitals

Third witch: We needed his heart. His warm, pounding, tiny, little heart.

No!!!

How powerful a muti does your son make?

And then I spy an urchin who looks like Kano near a garage. I ask Eric to stop the car. It is kano!

He cries softly. I crush him to my chest. I leave him in the car.

"Rasta, why?"

"It was a mistake. I am sorry."

Kano thinks that I am invicible because he saw me beat up Rasta so bad that the man fainted and that I had come to his rescue.

* * * * *

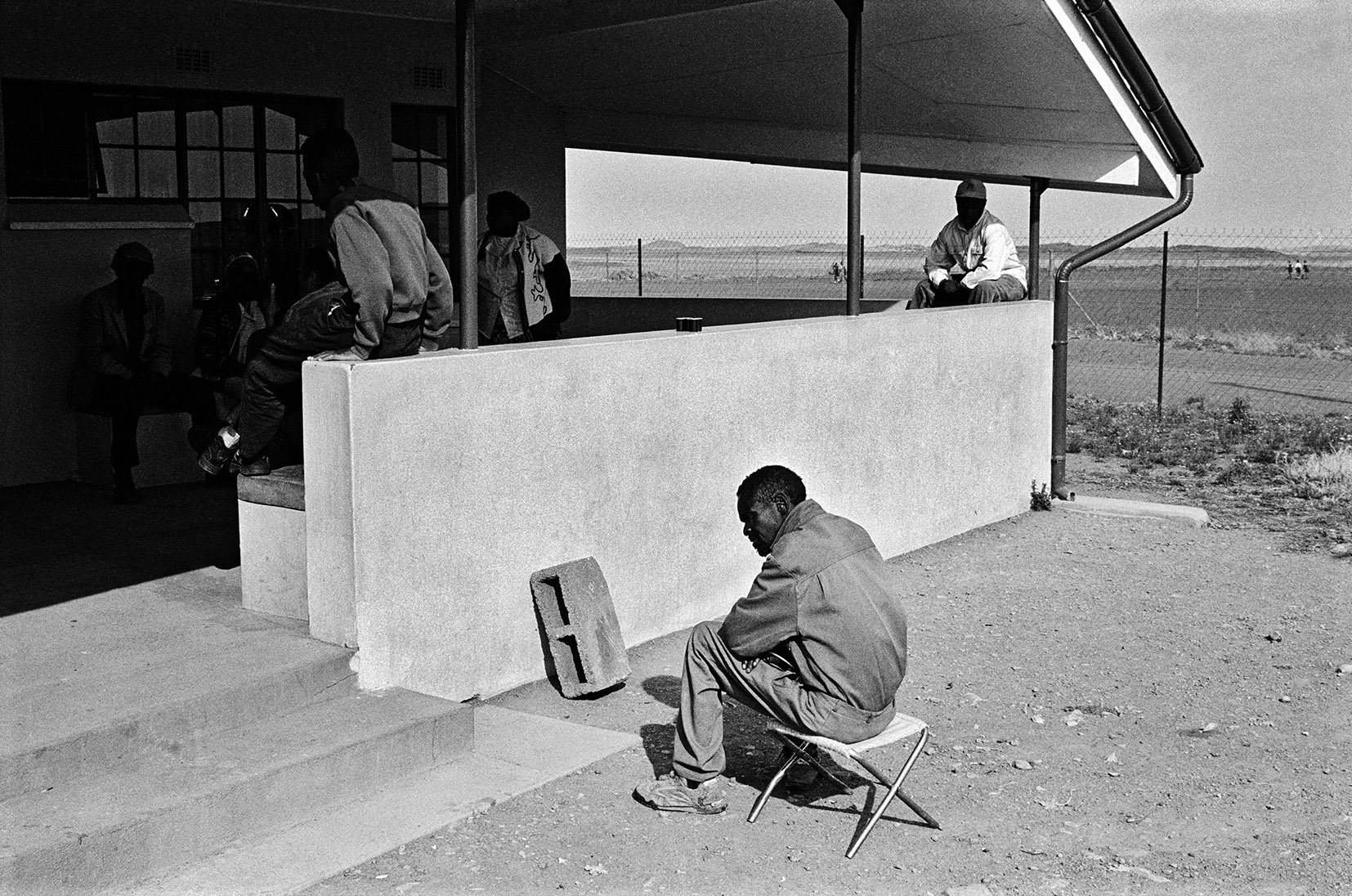

South-Western Transvaal, 1990.

I had been waiting in that taxi six hours for the passengers to fill up the two empty seats. The driver decided he is not going to budge. We are told to cram at the back of a one tonner, twelve adults. I say "This is criminal!" I am ejected from the taxi. The time is now almost midnight. Klerksdorp. Winter. There are no Hotels for blacks in this place.

I lug my camera bag, equipments and my clothes bag and walk. I wake up a driver who is sleeping in his car, ask for special delivery to Bloemhof. He offers space in his car until morning. I thank him and head for the freeway to hitchhike. I am mad. A taxi hoots and stops. I get in. I find the same passengers I was with earlier. Apparently they found another taxi with a driver willing to travel with fewer passengers to Taung. He had a funeral to attend there. The driver on being told about me made the detour to pick me up.

I get dropped off at Bloemhof city center. The town is dead asleep this time of the morning, except for the BP garage. The attendant allows me to sleep in a disused truck. He wakes me up at six o'clock before the owner comes to the garage. I pay him R5,00.

Bloemhof is a summer-grain producing rural town.

Bloemhof is a summer-grain producing rural town. There is also a small diamond prospecting industry. It looks like any other small frontier dorp which are dotted throughout South Africa. American functional architecture lines the main road that runs through the town. Banks, the roadhouse, a supermarket, police station, gas station and two hotels, one of them international. Well, international means blacks are allowed. Even so, here, the bars are segregated. The international hotel attracts little business from blacks. Truckers sleep in their trucks, travelling salesmen stop for fuel and eats and proceed on their way to anyone of Suns' hotels that are mushrooming all over the homelands. Those few who stop for the night do so mainly to have a drink at the bar and to screw the sex workers, who come from Boitumelong township, in their cars. On close inspection, Bloemhof is arranged neatly along race lines.

Indians have been pushed out of sight to the edge of town, away from prime commercial space. Essentially a small community, they live in a plot of land behind their shops.

Boitumelong, which means the place of happiness, is a blight on this landscape. It is about a kilometer from the town. A mild irritation, it is peopled by surplus farmworkers, who now compete for work at the creamery, the granary and a small diamond mining industry. The shops, hotel, shebeens, taverns and schools absorb a few more. The rest of the working force are migrants - travelling to and fro to Klerksdorp. There is a fragment of a coloured township farther away from the main road.

I work mostly on a farm 23 km from the town center, where I record the lives of tenant labourers. The family in whose hut I stay have come to accept me as family, partly because we share the same totem and partly because of my patronage. I have come to know the Maine family intimately.

September Maine calls me "abuti" Santu, in deference to my age. His cousin, Diyane calls me Motshwantshi - photographer. September is doing Standard 9. Diyane has been unemployed two years since his brief spell on the mines as a labourer underground. He is married and has two children. He wants to be Ngaka, a tradtional healer. September Maine lives with his parents in Boitumelong township. He is politically motivated while his cousin loves Kaizer Chiefs footbal team so much he tapes their soccer matches from the radio and listens to them over and over again. He has never seen Kaizer Chiefs play live, except on one of the two TV sets owned by the labourers in the 20 km radius.

September Maine on hearing the news of the unbanning of the ANC and the release of Nelson Mandela, organized a bus with other youths to Johannesburg to attend their rallies. Their journey was interrupted by police. He had been in jail when I saw him last, because of a riot in which a creamery truck was burned down. Something about his story reminded about my own life.

* * * * *

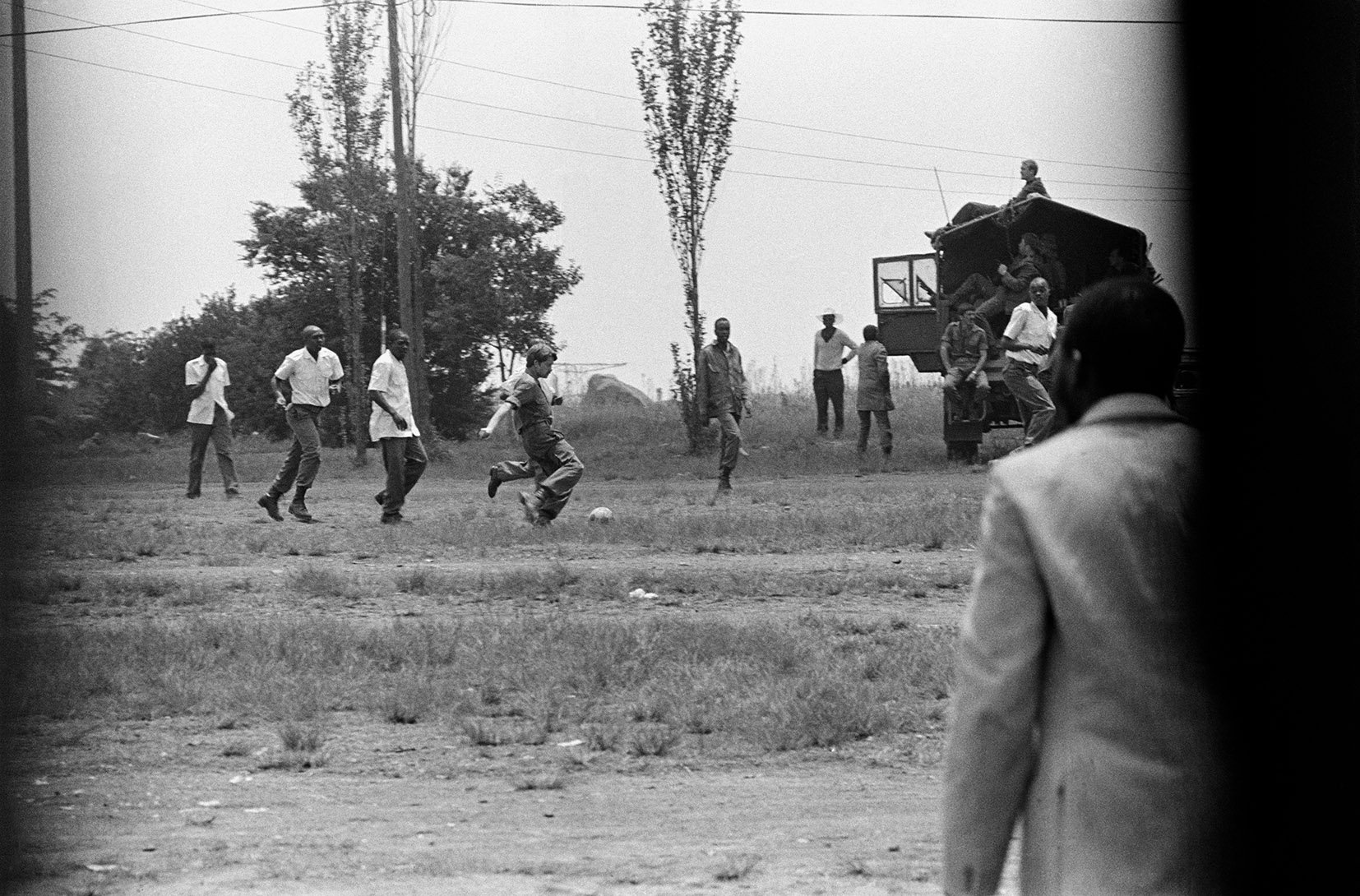

Soweto 1977

We are in a bus to attend Biko's funeral. Our bus leaves Klipspruit to join a convoy of other busses at YWCA in Dube. We arrive at Dube just after the police had dispersed the other travellers. There was broken glass shimmering everywhere around the place. Before I can assess the situation, our bus is flagged down by the police. The driver is ordered to follow their convoy of vans and gumba-gumbas, police-trucks. Our bus is stopped near the AME Church in Orlando West. All the while we are debating whether to tell the truth about our destination or to lie and say we are a football team on our way to the Vaal, at which point Ingoapele Madingoane interjects, saying that as the funeral is not banned we should be honest. We should be true to our convictions! Shamed, we keep quiet. Damnit!

A police captain enters the bus. He looks at us. The bus is surrounded completely by dogs, camouflage units and vans.

He says, "Waar gaan julle?" (Where are you going)

"We are going to Biko's funeral," replies Ingoapele, defiantly.

The captain says, "Ken julle daardie man?" (Do you know that man?)

He waits for no response, looking at the passengers sitting at the front, he barks, "Pas!" Where is your book of life? The dreaded reference book. The law says black people are expected to carry a book of life at all times, and to produce it on demand.

The passenger at the front responds, "Ek het nie." (I don´t have it.)

"Kom uit!" he says. (Come out)

"Pas!" to the next passenger. "Ek het nie!"

"Pas! Pas! Pas!" pointing at passengers at random. To choruses of I don't have it and Ek het nie.

"Nee, God. Kom julle so maar uit. Almal." (Oh, God. Come out all of you.)

Looking at Ingoapele. He says, "Jy is die leier. Kom met my." (You are the leader. Come with me.)

While we hesitate, because we were seated in the back, looking out of the window, we ponder what's waiting for us outside. Sjamboks. Dogs. Guns. Boots, Fists. Truncheons.

Ingoapele was given the special treatment. I saw him through the window levitating. Boots, dogs, fists, sjamboks and other weapons which were not official police issue.

Coming off the bus, you had to go past a file of police until you entered the van, which could not take us all in. Bludgeoned by each of them, with no possibility of escape, we ran until we reached the van, where we squeezed, stampeded in an effort to escape the beatings.

We were taken to the Meadowlands police station charge office. Details of how we got there I can't remember. I am leaning against the wall, watching the proceedings when this black camouflage policeman singles me out.

"I see," he says, "Ufaki Botsotso," referring to my stove-pipe tights. He punches me in the stomach.

"Ne Florscheim." (And Florscheim shoes). He was wrong, my boots were Italian make.

He stamps on my toes with his boots. I wince. He kicks me in the ankle. Another punch in the ribs. Slowly and methodically without rancour he gives me the beating. Body punches, ankles and then toes. I am trying to keep a brave face. All the time I am fighting an impotent rage. He is alternatively feigning a punch and stomping on my toes. When I realize that this is not stopping, I plead with him, fighting back tears. There were women in the charge office. There is no way I am going to cry.

"Why are beating me?" I ask.

"Ngi ya guqhapaza." (I am simply picking on you.)

"Why don't you pick on somebody else?"

"Ngi funa wena. uQabanga kuthi umhle. Nami ngi funa iFlorsheim." (I just want you. You think you are smart. I also want a Florscheim.) Punch.

The case against us is later withdrawn.

* * * * *

Johannesburg 1976.

I am standing in the dock after the demonstrations in the city of Johannesburg. The magistrate mumbles something. The interpreter looks at me.

"E kae pasa ya hao?" he says. (Where is your refence book?)

I say I don't have it.

At this stage, my mom who is sitting in the audience stands up. She produces my reference book. I give her a cold stare. Will her to disappear. A court official takes the reference book from her, gives it to the magistrate. Oh mother, you have done it, I curse under my breath. I was hoping to get away with a simple reprimand had my mother not produced the bloody document. There were no criminal charges against me.

The magistrate fiddles with my reference book checking for endorsement in it. Mumbles something. Case remanded in custody and referred to another court, to investigate charges of vagrancy. The Section 29 law is applied to black people with 10.1.(d) qualifications (alien residents), and it carries a two year, no fine sentence if found guilty.

I had been in town on the day the student of Soweto decided to take the demonstration into the city centre. Walking down Pritchard Street and von Brands this old man chats me up. He is wearing Safari suits and he asks me to follow him. He holds my hand and I follow trying to convince him to let me go.

His tone changes from being conversational to one of authority. As we turn the corner, I take one look at the gumba-gumba and panic. I prise my hand free and I run. Turn back into Pritchard Street. I don't know where these two athletic apes came from, they give chase. Dodging between dustbins, one of them with his open arms knocks the bin down. This is getting serious.

I run across the streets hoping to disappear in the OK department store. A car bumps me trying to knock me over. Near the door of OK an old man pretends to give way for me to pass and trips me. I go crashing on the floor. My senses go numb. Those two apes catch up with me. I get knocked about a bit.

My older brother Ishmael happens along. He is driving a motorbike, a messenger at his place of employment, and doing his rounds. He sees me being beaten up. He cries, wants to take my place in the beatings. He turns his bike around. Sees me being bundled into a car. He feels helpless. He drives back to where he works. He dumps the motorbike and the letters he was supposed to deliver. His employers are astounded. They ask him what the problem is.

He says, "Your people are killing my brother," and he leaves for home to inform Mom.

I was hoping to get away with a warning in this court. Until mom brought that bloody document.

* * * * *

I had travelled 340 km to a remote place where on my first arrival I thought it was beyond hope. A landscape that is bleak, the elements inclement to farming. A land where by my own light, the Vervoerdian dream was in place, well almost. But for the blight on the landscape, just beyond the horizon. Ironically named Boitumelong.

September calls me abuti (his brother), he defers to my opinions. I sometime wonder if I deserve his respect. I was never an activist, not in the popular sense. When he told me about his turmoil at the hands of the police, I could not applaud him.

* * * * *

Soweto 1991

I am disillusioned by my work as a journalist and documentary photographer. Having put up a show at the gallery, seeing how my work gets absorbed, interpreted and assimilated into the mainstream, I have questions on the efficacy of photography making interventions, and mobilizing people around issues. I am not making photographs.

Suddenly after much reflection I decide to copy photographs that people keep in their homes, in the hope of devising a dialogue between my images, which are primarily made for the media, and photographs people keep as repositories of memories in their homes. The work progresses earnestly, with Charles´ encouragement at the African Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand. Thomas, my colleague and fellow researcher, homes in on Salome who has photographs of her parents, in their youth. The family agrees to me making copies of the photographs. The light outside is fading fast. I put off the shoot for another day.

A few days later we arrive at Salome's home in the early afternoon. We find a youth waiting for us. He wants to know what we are all about. I begin to explain. Thomas leaves the house to wait in the car. I find this odd. This youth, truculent and all, refuses permission for us to make copies. What is going on? I thought this was just a formality. This youth, I must admit, has caught me off balance. He is very articulate. He was prepared for everything, so he admitted later. To him, this was a contest of wits. Something he said remains with me now:

"Do you like what the white man has done with our history? Look at Dingaan. He is portrayed as a fat and idle chief."

Do you think Gatsha Buthelezi had thought about that when he accepted the role of a "fat" Cetswayo in the film "Zulu."

* * * * *

Johannesburg 1986

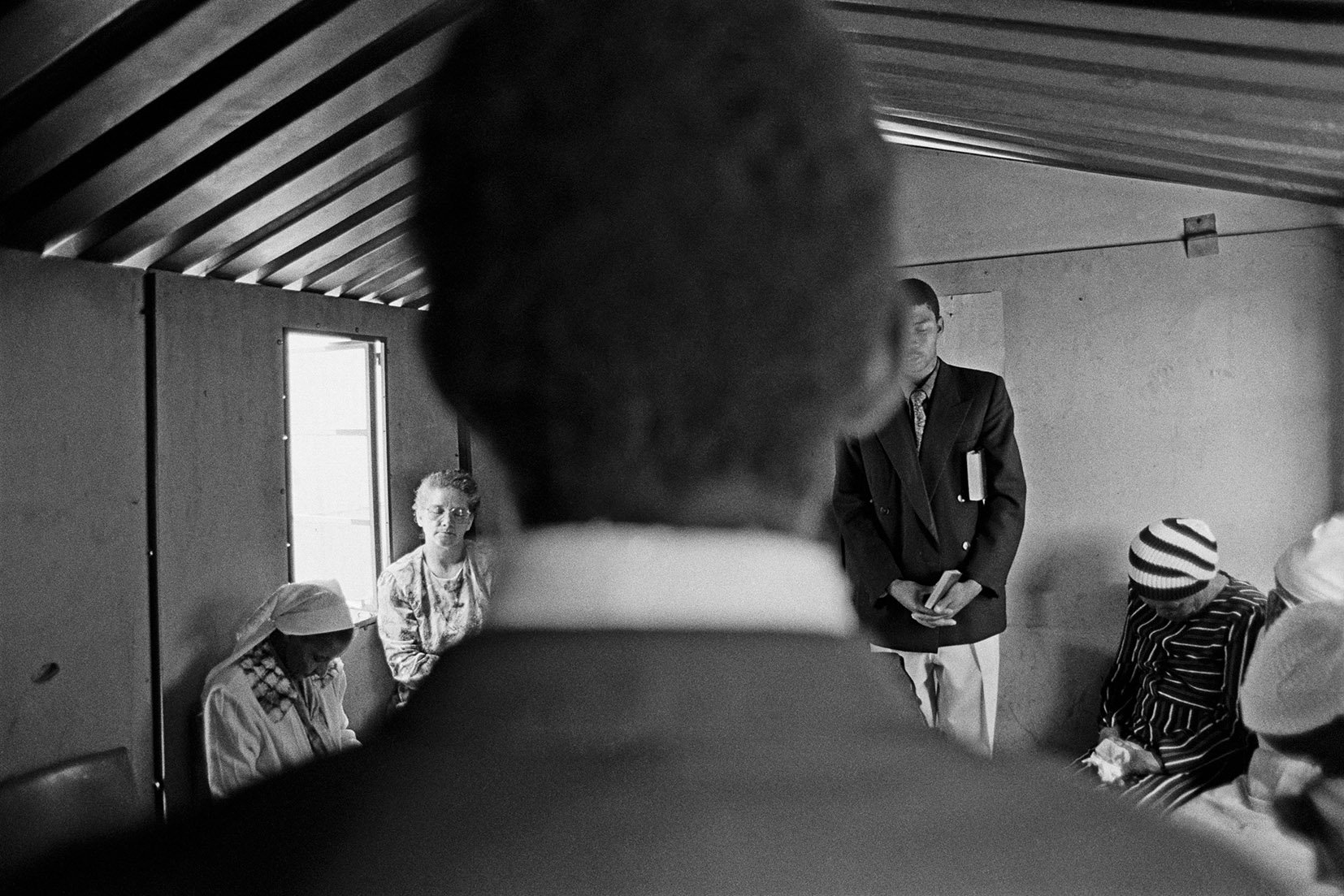

I am printing in the darkroom at Khotso House when Audrey Coleman calls me to come and help with interpretation. She had a group of five boys who needed help. She could not understand what they were saying.

I walk with her to where the boys are. I estimate their ages to be between fourteen and one who is seventeen or eighteen years. She asks me to find out their story. I greet the boys in Zulu.

"Comrade, you see we are from the Vaal. We are progressive and we have been pushing the line. Yes, and so on. We have been recruiting new cadres and feeding them progressive politics. We have also been involved in serious operations. Out mission being to mobilize the masses in the Vaal and to neutralize the system."

"What are they saying?" says Audrey.

"They are comrades from the Vaal." I turn back to the boys and switch languages. "I am listening."

"We are the ones who killed the councillor, Jacob Dhlamini. We have also been petrol bombing houses of policemen in the township. You see, our targets are police in their vans and the homes of sellouts. We want to eliminate them completely, comrade."

I become apprehensive. I turn to Audrey and say, "These boys belong to a youth movement in the Vaal. They have been involved in various demonstrations there. Some of their friends have been taken into custody since the death of the deputy mayor. They are afraid they might also go to jail."

"Ask them what would they like us to do form them."

"And so, comrades?"

"The system is on to us. We are afraid for our safety."

"Why are you revealing all these things to me or to anyone for that matter? What makes you think you can trust me or her, comrades?"

"According to our thinking, we have done our job for umzabalazo, comrade. We need help. We need to go into hiding. We also need transport to skip. We would like to go and train in the bush."

"Who told you can find help here?"

"Well, we were told Khotso House helps people, and they are on our side."

"What are they saying?" Audrey asks.

"They say they need a place to hide, and money because they are hungry. They have been on the run for a while."

"Ask them how they came here."

"We came by train, riding "staff" and we walked part of the way." Riding staff means travelling without paying.

I repeat this to Audrey.

"Tell them they need a lawyer, a good one. Tell them also that although the council of Churches has places of safety for people who are persecuted for their political beliefs, most of these are priests and church people who believe in non-violence. We cannot jeopardize the safety of those places and the people who use them by taking them in. We can't meddle in politics. The police would not hesitate to raid Khotso House. We would not be able to justify why they should not."

"If I were you, I would be careful who I tell your kind of story. The people here are religious. They do not believe in violence. They are church people. Go to the African Life Building. There is a lawyer there who takes political cases. Especially cases like yours. He might be able to help you."

I go back into the darkroom stunned by what I have just heard. Steve comes to me and says, "Do you know what the revolutionary program is?" I say no.

"The whites will strategize it, Indians will finance it, Coloureds will preach it and blacks will fight it."

* * * * *

Darragh House 1991.

The phone rings.

"Have you received the summonses yet?" It is my wife.

"No."

"This thing bothers me. I actually paid for them to be delivered to you."

"When's the date."

"Tomorrow. Are you going to come?"

"I don't know."

"It's up to you. I thought you might like to see how the whole thing is resolved." she probably means dissolved.

"What are your grounds?"

"You will find out. It is not something you don't know."

I am there early. She is late. We greet each other.

"Have we been called?" she asks.

"Not yet."

We wait. We are the only couple, the other people come mostly alone, with friends or relatives. Just another case of matrimony gone bad. I am wearing a suit. Last time we were at court together we were getting married and I had to borrow a jacket from my wife's brother-in-law, who was a clerk in these offices, which were then called the Department of Cooperation and Development.

Our names are called. The clerk/interpreter motions her to the witness stand. She is sworn in. The clerk asks me to sit myself on a chair near him. The magistrate asks her questions. She responds.

I listen to the proceedings, quietly, waiting for my turn at the stand. An unflattering portrait of me is being painted in words. I am hoping for a kind word, a refrain, or a 'but' even. The picture of me that emerges is that I am a drunk and violent man.

"Divorce granted."

I walk her to her place of work. I don't know what I am feeling at the time. I go home and make a few calls to friends and relatives. They tell me how to feel.

* * * * *