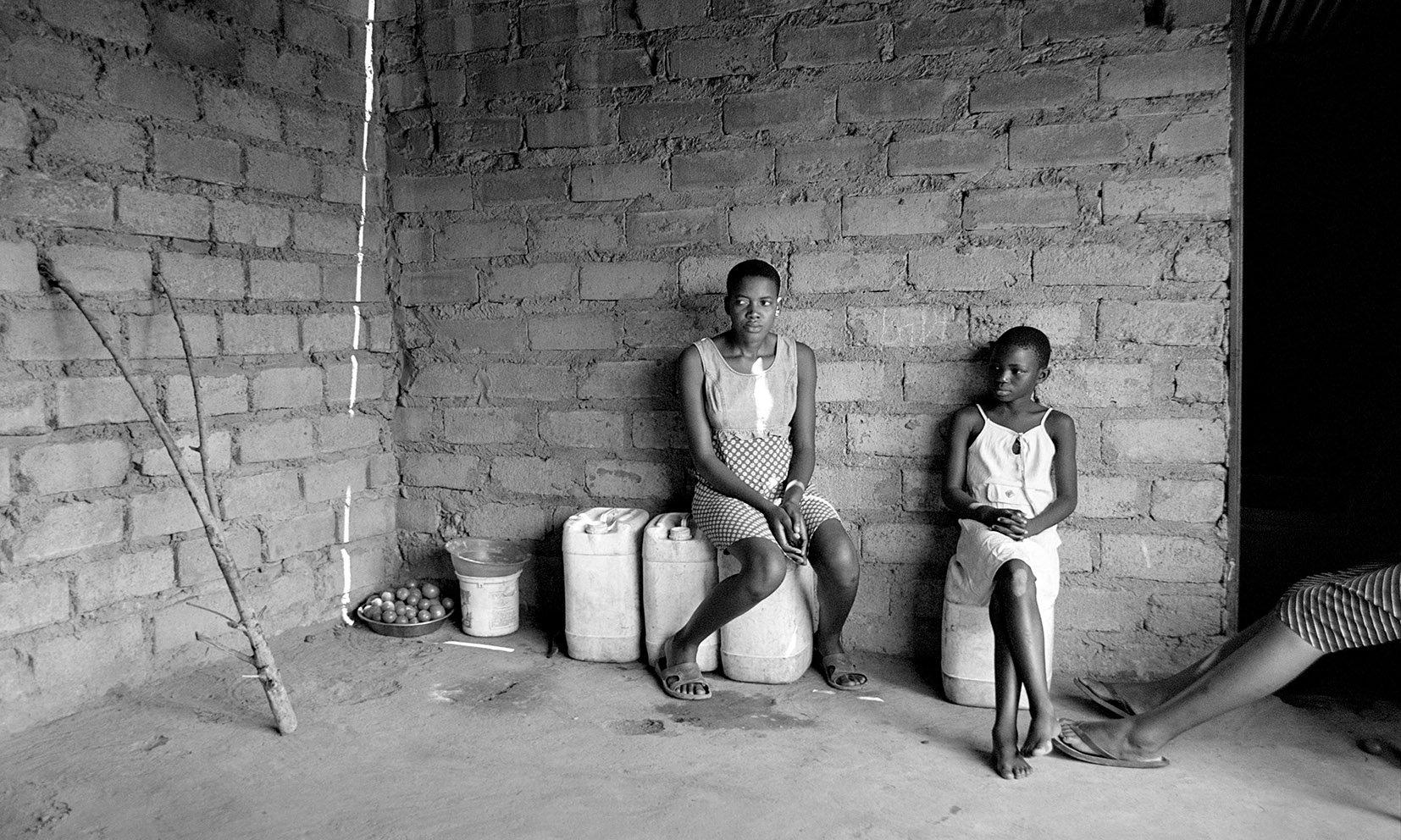

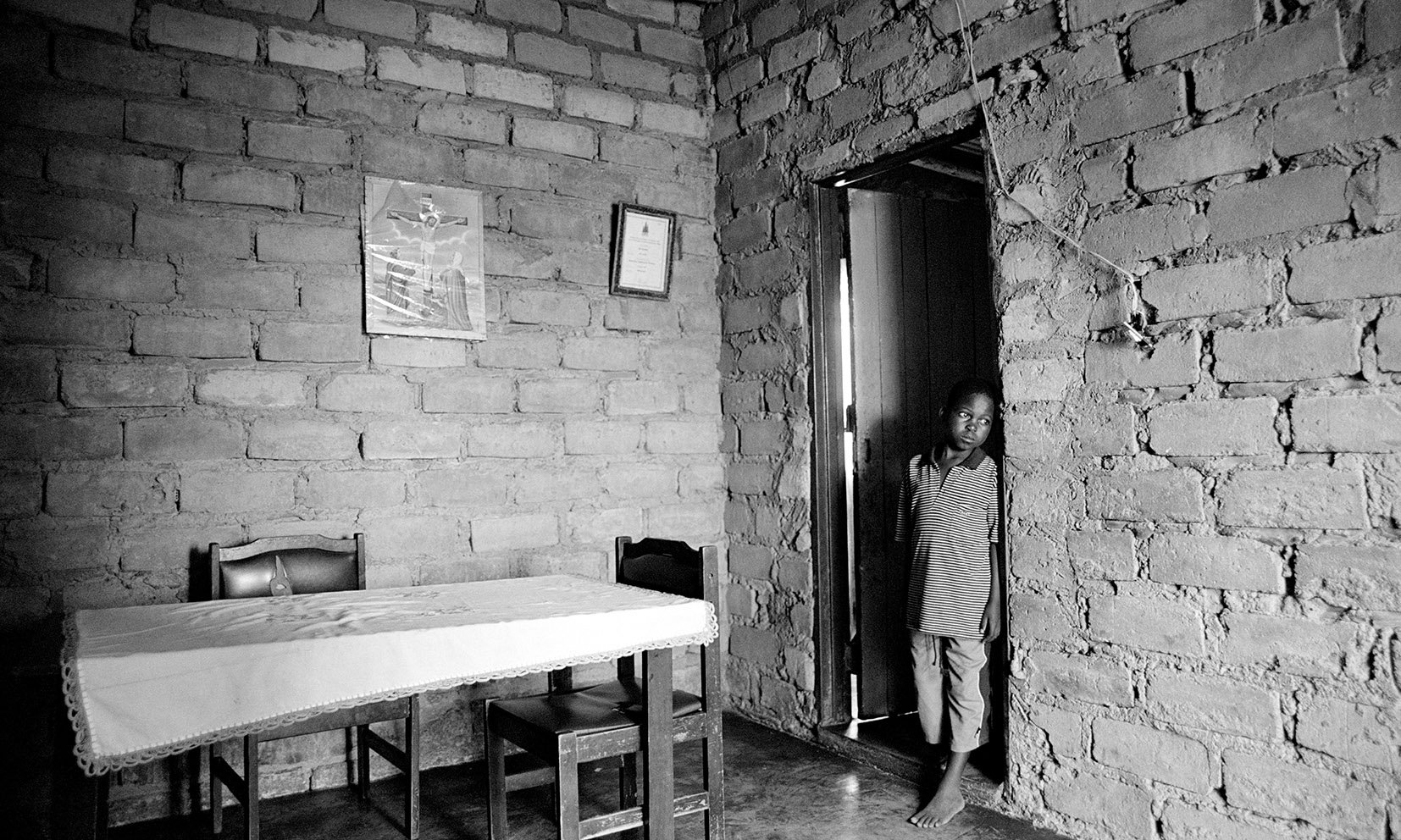

Child-Headed Households

One danger with documentary photography, especially “victim photography” is that it may create its victims as much as it finds them. (Abigail Solomon-Godeau)

Child-headed households

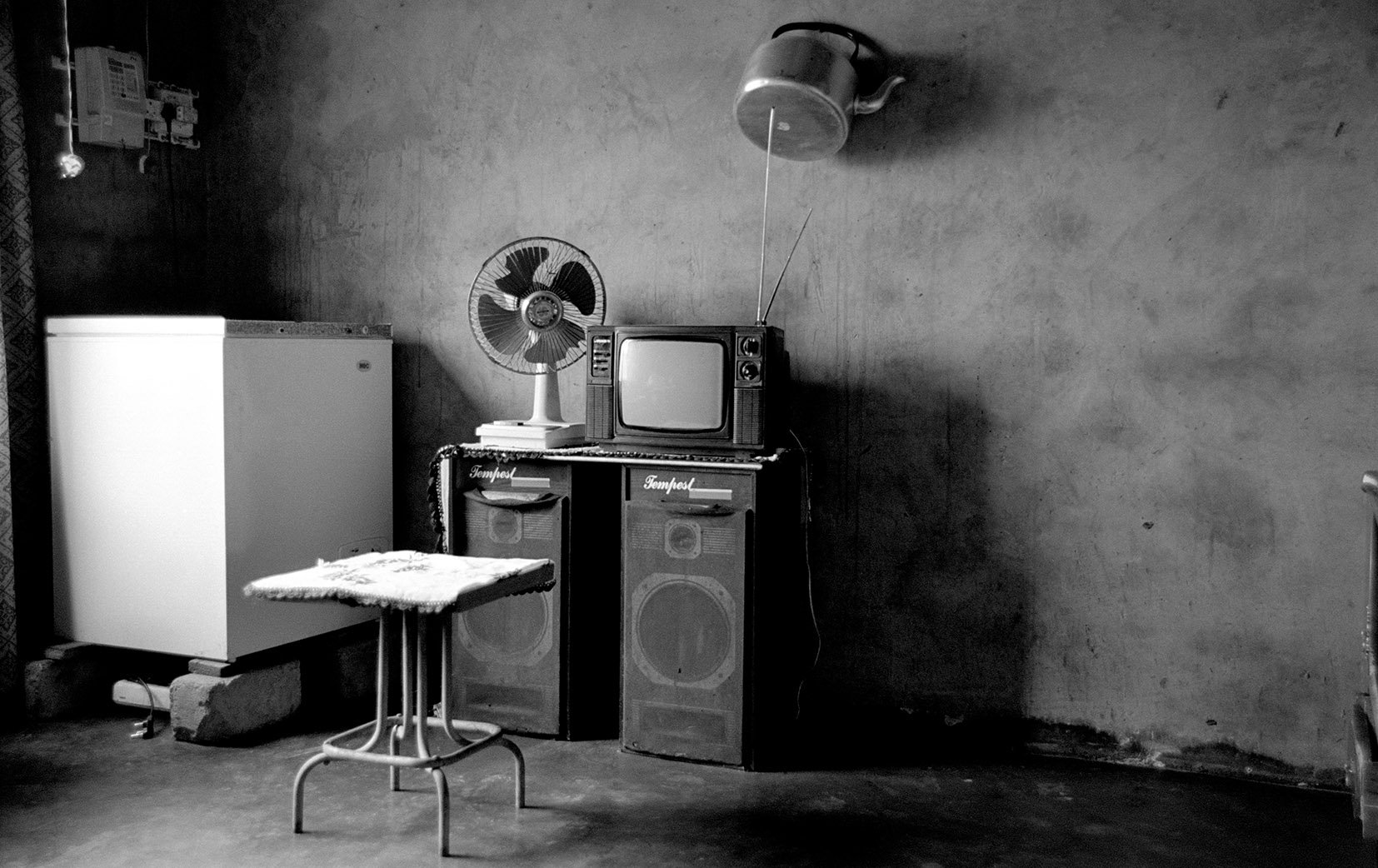

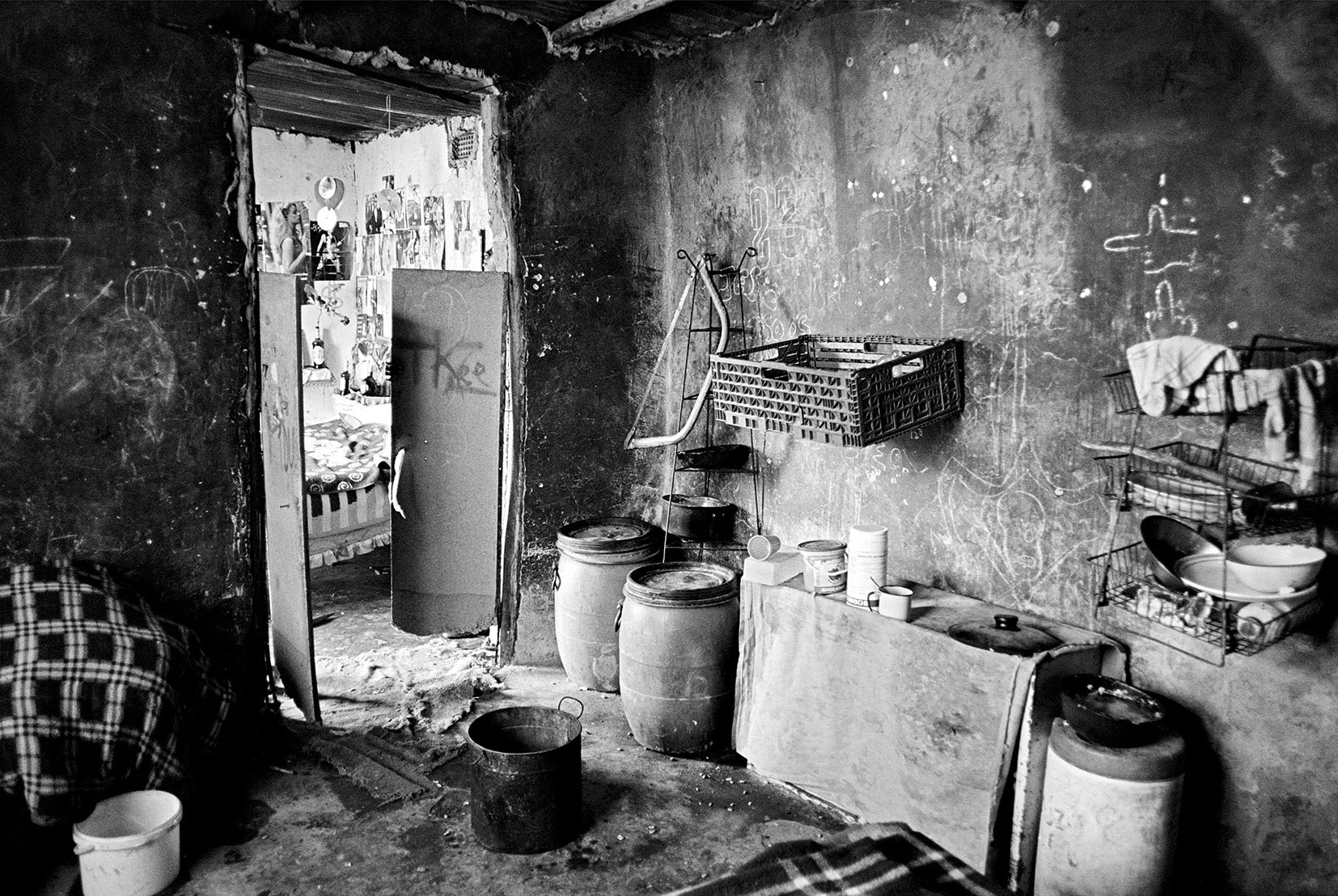

Urban Lenyenye and rural Dan, two nondescript sprawls skirting the Tzaneen metropole in the Northern province, interface in a deadly embrace, their physical boundaries indicated only by the quality of road. Where tarmac gives way to mud you are entering the rural. The proximity/divide of the two districts is insignificant, rather arbitrary, an administrative chimera when viewed from the perspective of their everyday intercourse. Except, it is a fateful one for those people who have the HIV virus or those living with AIDS.

Until recently, interventions through Aids education and anti-retroviral drugs were more readily available to people in rural villages such as Dan, Pharare and Shiluvane, than it was to denizens who inhabit urban townships such as Lenyenye. These interventions: provided for by

assortment church and other formations, NGOs and philanthropic societies; at best difficult (resources), was made impossible because of government administration and policies (access). To this mix factor-in ‘rural’ and the irony is made all the more chilling. In this context rural means ‘Chiefdom’; (read: antonym of urban and progressive) “steeped in tradition, archaic belief systems” and, all that this entails. Death certificates in Dan, Pharare and Shiluvane, routinely ascribe cause - even to early death - simply to natural causes.

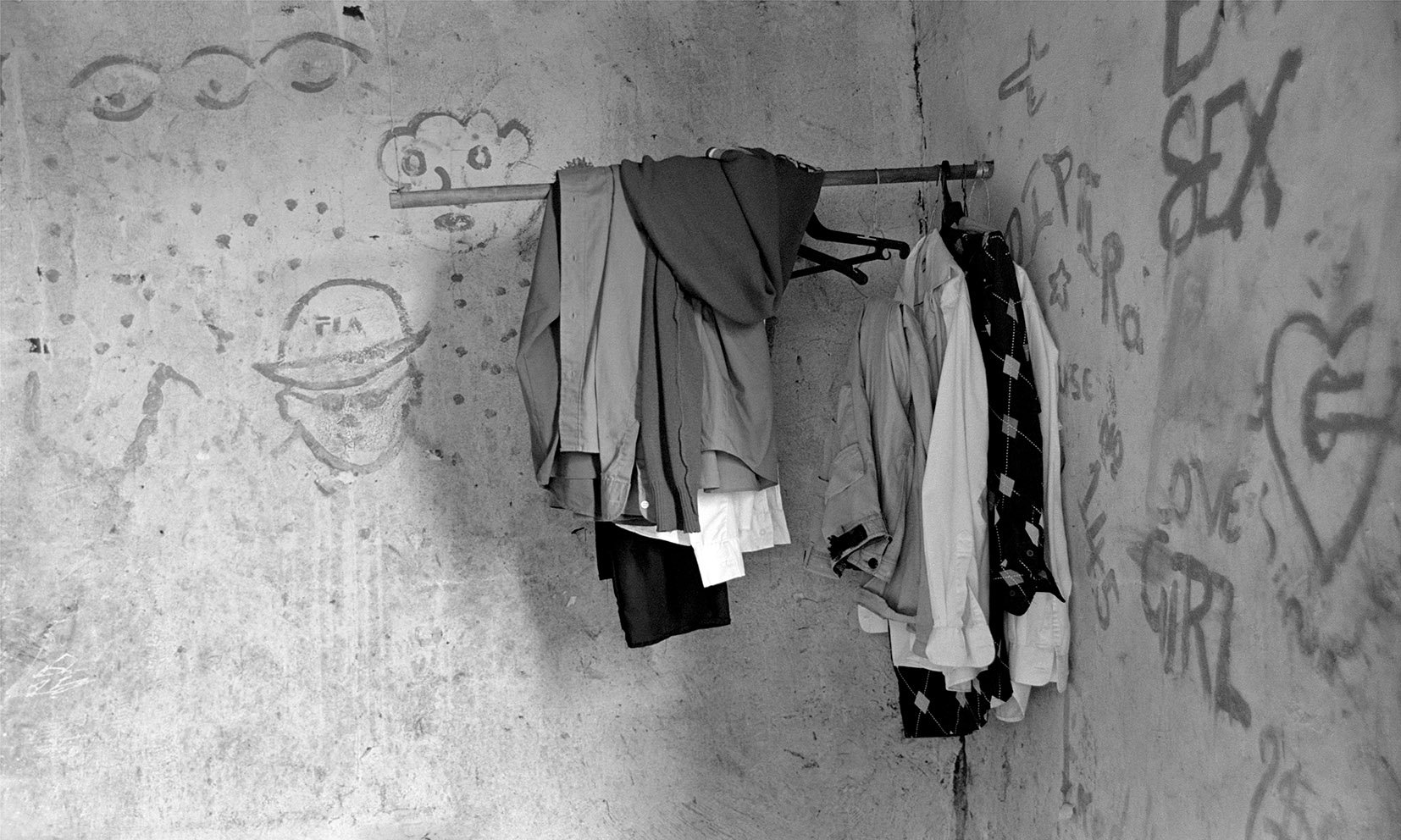

Whereas it is normal that death in a family often necessitates adjustments in roles and responsibilities; in ‘traditional’ societies (preferably ‘transitional’), death can and often does upset strictly observed gender roles in those settings.