Landscapes

Santu’s landscapes

“...[Does] the black man anyhow ‘appreciate’ the landscape any better than an animal does...” J.M. Coetzee

"The predicament of private is shown by its arena. Dwelling, in the proper sense, is now impossible. The traditional residences we grew up in have grown intolerable." Adorno

Democratic South Africa is yet to take psychic ownership of the land it has inherited from the Apartheid ancestor.

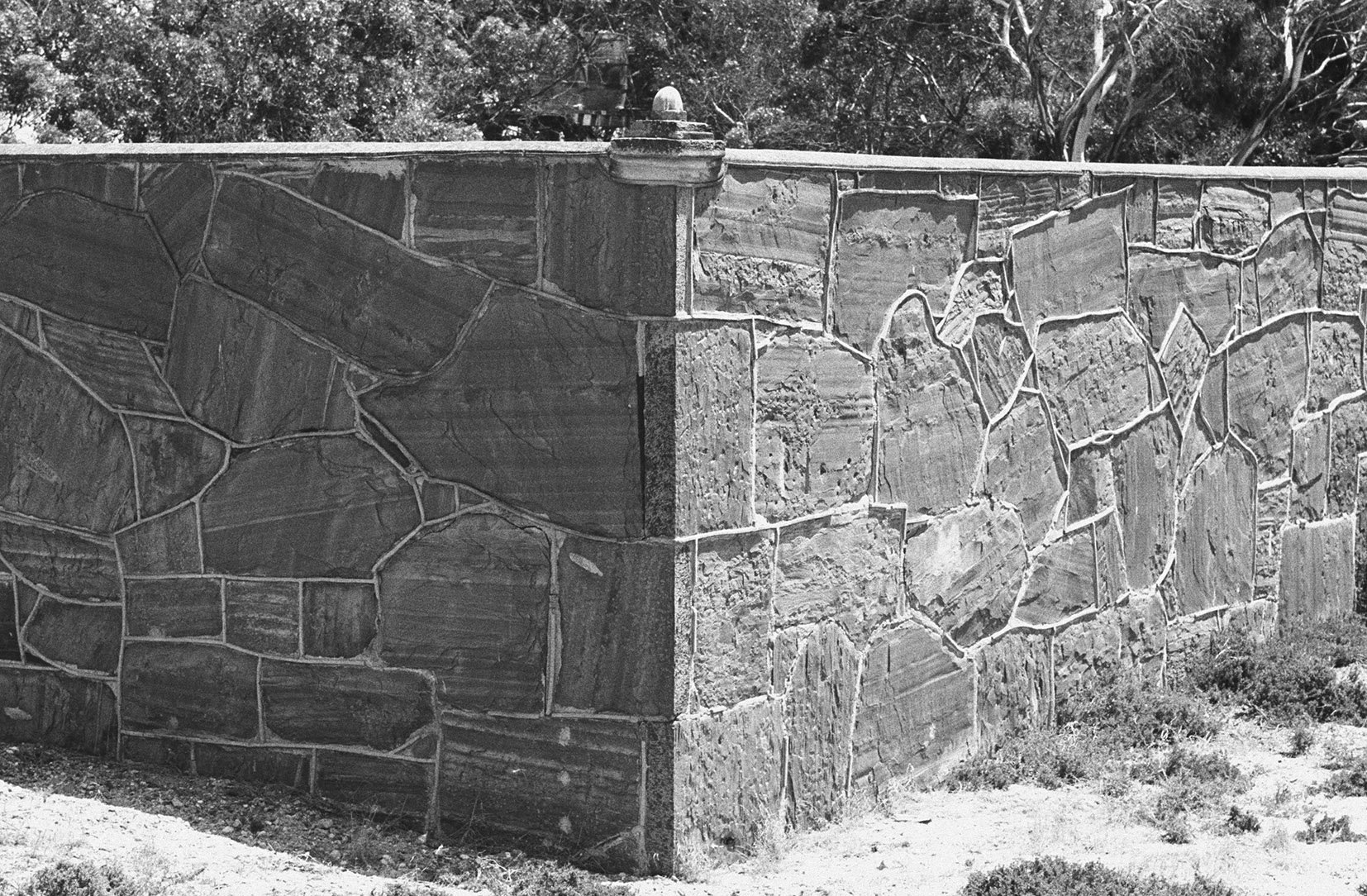

In South Africa formal landscape appreciation is fraught, so is the history. If one were to ask, who owns the South African landscape? A cacophony of sounds, narratives and narrations, a delirious, rather, a deleterious mix of claims will be the response, many more than there are colours in a rainbow. To be sure, until 1994 Afrikaner authority and sense of propriety superseded all other narratives. You see this in the literature in libraries (Herman Charles Bosman), in art institutions and museums (Pierneef), in monuments and memorials (Voortrekker Monument) and in the nomenclature (meerkats) and place names (Karoo). Under Apartheid my movements within the republic were proscribed.

Let me preface, every time God gets embroiled in real estate it means trouble.

The beauty of the South African landscape has a history that is at once bizarre, hilarious and fantastic. It is wrapped up in biblical mythology overlaid with some Africana mysticism. South Africa is ‘the promised land’ to some. The country is peppered with place names such as Bethlehem, Nineveh, Nieu-Bethesda, Weenen and Nylstroom, and this says something about the denizens who held the place in custodianship for God. We once had a holiday named ‘Day of the Vow’ or ‘Dingaan’s Day’, and it was the day for “kaffir hunting”.

To most people landscape photography is a genre suitable to the limp-wristed. Better, it is considered

irrelevant in a country with a strong social documentary tradition. I agree with Schama when he says, "Landscape is a construct of memory, it is a work of the mind, built up as much from the strata of memory as from layers of rock”. In Putting Identity in Its Place, Basso has written that self-knowledge cannot be constructed without place-worlds. “Knowledge of places is closely linked to knowledge of the self, grasping one’s position in the larger scheme of things, including one’s own community, and securing a confident sense of who one is as a person”. To this I aver that identity is implicated in the landscape, seeing that whenever I travel the world my identity is designated South African – border policemen, customs authorities and people I interact with when I am abroad tag South Africa to my identity.

These are issues that partly explain my landscape project: reclaiming the land for myself. And since 1994, in theory at least, I am free to travel everywhere within the republic.

In this project I am careful to use the word landscape in its modern meaning and sense. I would like to posit that landscape appreciation is informed by personal experience, myth and memory, amongst other things. Suffice to say, it is also informed by ideology, indoctrination, projection and prejudice.

I am looking at the interface of the inner and outer – interior/exterior - worlds, where the objective/subjective environment inform/determine the experience of being at a given time and space. My approach to landscapes is informed by the cleaving the word landscape into its portmanteau component parts: ‘land’ (the verb) and ‘scape’ (to view) in order to illuminate and decode how we view landscape, and that this is based on our experience, knowledge and sometimes, stories.

Santu Mofokeng

18 July 2008

Simon Schama, in Landscape and memory (New York: AA Knopf, 1995).

Basso 1966:34,cited in Landscape, Memory, Monuments, and Commemoration: Putting Identity in Its Place, Osborne B.S. 2001 (paper).